Ancient burial site upends what we know about Stone Age men, women, and children

For a long time, the Stone Age has been painted in narrow strokes – men hunted with stone tools, women cooked, and children watched.

This idea shaped research, museum displays, even the way skeletons were identified. But the ground in Latvia is telling a very different story.

At Zvejnieki, one of Europe’s largest Stone Age cemeteries, archaeologists have found that tools buried with the dead were not just men’s possessions. Women had them too, so did children.

The way these objects were placed in graves shows they carried meaning far beyond daily work.

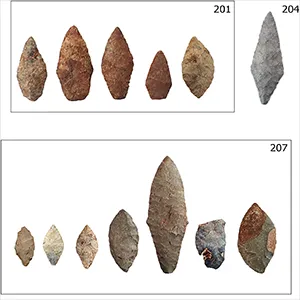

Ancient graves and Stone Age tools

Zvejnieki sits near Lake Burtnieks. The site has more than 330 graves, spanning over 5,000 years. Excavations began in the 1960s and continued for decades.

Thousands of ornaments made from animal teeth and amber came out of the ground. Red ochre stained the soil around many skeletons. These details have been studied again and again.

But stone tools? They were mostly ignored. Archaeologists thought of them as practical. Not decorative or symbolic. Just leftovers of everyday survival.

That view collapsed once Dr. Aimée Little and her team returned with new tools of their own.

Women, children, and Stone Age tools

The Stone Dead Project used microscopes to search for tiny traces on the artifacts. The team studied how each tool was made, used, and finally placed in graves.

The results surprised everyone. Some scrapers showed wear from working animal hides.

Others looked fresh, almost untouched, as if they had been created only for burial. And many were broken on purpose before being laid to rest.

These details reveal that stone tools were not only about survival – they were part of rituals. Part of how people said goodbye, and part of how they thought about life and death.

The discoveries challenged long-standing ideas about gender. Women were just as likely, sometimes even more likely, to be buried with stone artifacts. Children and older adults received them too.

That makes the picture clear: these objects were not reserved for hunters. They belonged to everyone.

“Our findings overturn the old stereotype of ‘Man the Hunter’ which has been a dominant theme in Stone Age studies, and has even influenced, on occasion, how some infants have even been sexed, on the basis that they were given lithic tools,” noted Dr. Little.

Changing traditions over time

Burial practices at Zvejnieki shifted. In earlier centuries, tools were rare in graves. Later, by the 4th millennium BC, deposits grew larger.

Some people were buried with dozens of flint artefacts. Many had never been used. Their role was clearly symbolic.

This change matched wider cultural shifts across the Baltic. Communities began to use more red ochre. They buried people collectively.

Clay death masks appeared. The inclusion of flint tools fit into this wider move toward more elaborate rituals.

What the tools reveal

Micro-wear analysis showed patterns that jumped out. Scrapers often carried traces of hide working, suggesting that preparing skins was a valued activity even in death.

Bone and butchery marks appeared on some pieces. Mineral traces, connected to ochre, turned up only in female burials. That detail hints at gender-specific ritual roles.

Bifacial points – long seen as hunting weapons – often showed no use at all. They were made, broken, and buried. Their meaning was symbolic, not practical.

Destroying them may have been part of letting go, part of a shared tradition that stretched beyond one community.

Stone Age tools and special graves

Some graves stood out. An older child was buried with more than 40 tools, many unused, alongside ornaments of amber and animal teeth.

Another grave, belonging to a young woman, contained primary deposits with her body and additional offerings at her feet.

These were not random choices. They were deliberate acts, full of meaning for the people who stood around the grave.

These burials show that women and children were not peripheral. They stood at the center of ritual traditions. Their graves and the valued tools inside carried messages for the living.

Breaking old assumptions

The implications are clear. Tools in Stone Age burials were not simply for men. They were symbols for everyone – men, women, children, and elders.

They carried social meaning and were part of rituals that bound communities together in the face of loss.

“This research demonstrates that we cannot make these gendered assumptions and that lithic grave goods played an important role in the mourning rituals of children and women, as well as men,” noted Dr. Anđa Petrović, from the University of Belgrade.

Why this discovery matters today

What might look like simple flint flakes turn out to be keys to identity, memory, and ritual.

They tell us that Stone Age communities valued more than hunting. They cared about symbolism. They cared about honoring all their members.

“The study highlights how much more there is to learn about the lives – and deaths – of Europe’s earliest communities, and why even the seemingly simplest objects can unlock insights about our shared human past and how people responded to death,” said Dr. Little.

The study shows that re-examining overlooked artifacts can transform our understanding of the past. At Zvejnieki, stone tools are no longer just tools.

They are stories carved in flint, carrying the voices of communities that lived, grieved, and remembered.

The research is published in the journal PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–