Scientists make a surprising discovery while searching for a shipwreck in Antarctica

Scientists searching for Shackleton’s lost ship in Antarctica expected to map old wood and scattered debris. Instead, they found more than a thousand carefully arranged fish nests spread across the seafloor.

The discovery lies in the western Weddell Sea, under ice-covered waters more than 950 feet deep off the Antarctic Peninsula.

The work was carried out aboard the SA Agulhas II, a South African icebreaking research ship used for scientific missions in Antarctica.

Fish nests and shipwrecks

The Weddell Sea Expedition brought together polar experts to study thinning ice shelves, document little known marine life, and hunt for Shackleton’s famous shipwreck.

Organizers described it as a pioneering Antarctic expedition that aimed to answer basic questions about one of Earth’s least studied seas.

The work was led by Russell B. Connelly, a marine biologist at the University of Essex in the United Kingdom.

His research focuses on how Antarctic fish use the seafloor to reproduce and how those breeding sites respond to environmental change.

Before the discovery, this stretch of seafloor lay beneath an ice shelf hundreds of feet thick, with no route for ships.

When the giant iceberg A68 broke away in 2017, it opened a window into waters that had not seen daylight for decades.

On one of the descents, the tethered robot Lassie skimmed just above the bottom, its cameras catching shallow, circular hollows cleaned of loose silt.

What first looked like simple dimples quickly resolved into individual nests, each guarded by a fish or marked by the traces of recent care.

Ice fish claim the nests

The nest makers are yellowfin notie, Lindbergichthys nudifrons, a small icefish that rarely grows longer than about 8 inches.

These fish belong to the cryonotothenioid, a group of Antarctic fish adapted to extreme cold, lineage.

They mature slowly, often taking four or five years to reach breeding size, and they produce relatively few, large eggs.

Instead of leaving those eggs to drift, parents invest heavily, with one adult remaining at the nest site as a full time guard.

Architectures in the deep

Reviewing the robot’s footage later, the team found nests at five separate sites spread across miles of soft seafloor.

In each location, many of the shallow bowls were still clean and clearly maintained, showing that parents had only recently left.

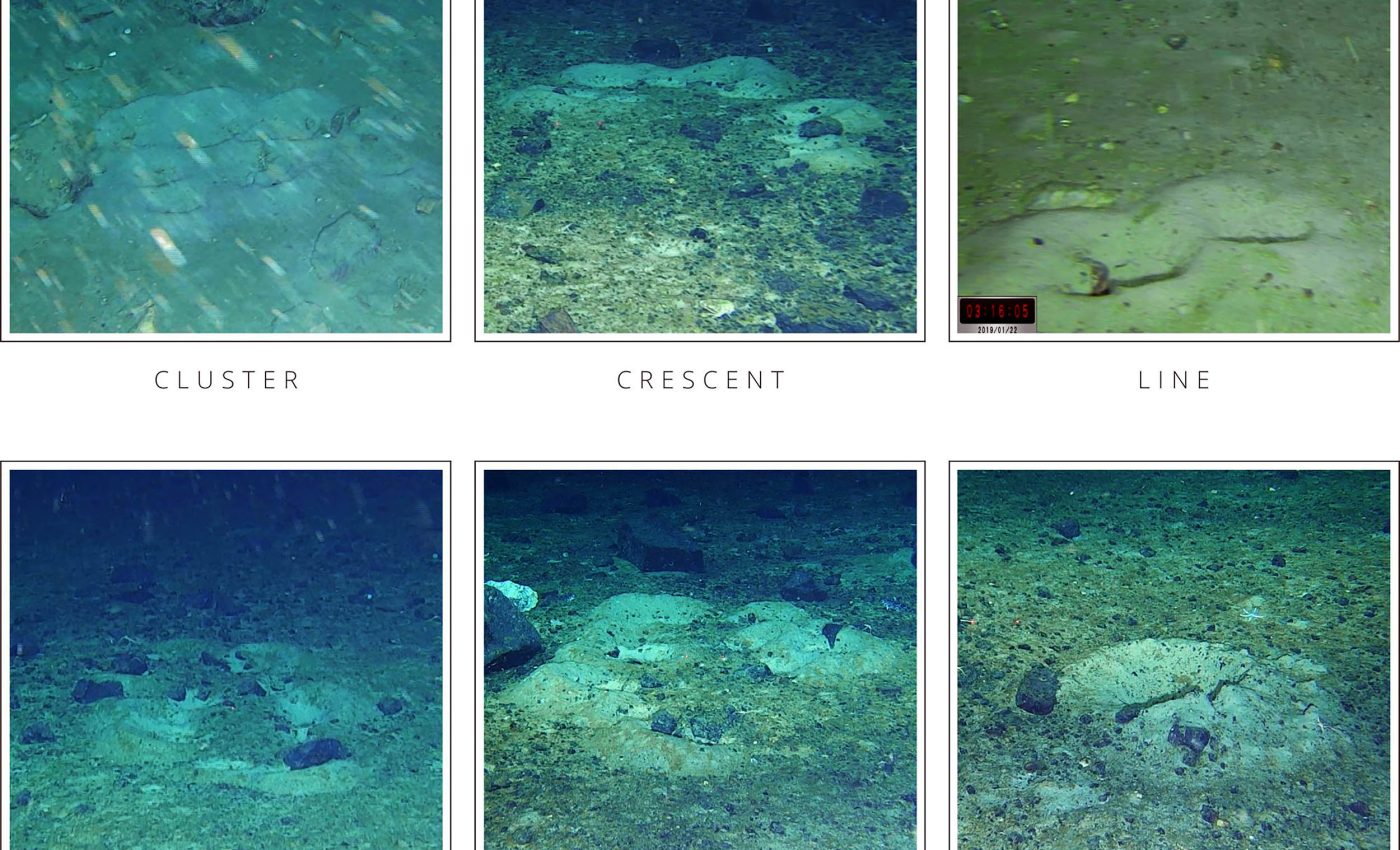

When researchers plotted where each nest sat, they saw six distinct layouts rather than a random scatter.

The designs included lines, crescents, ovals, sharp U patterns, tight clusters, and a final category of isolated nests.

Cluster formations dominated, with more than two fifths of all nests jammed together into compact groups. The pattern fits selfish herd theory, an idea where animals use crowds to cut personal danger.

Potential predators such as brittle stars and ribbon worms often lurked on nest rims, close enough to grab stray eggs or larvae.

Yet water just above the nests stayed slightly below freezing and closely matched the wider seafloor, suggesting behavior, not temperature, shaped patterns.

Why this matters

The Weddell Sea, in the Atlantic sector of Antarctica, remains one of the least disturbed ocean basins.

Thick winter sea ice and difficult access have limited fishing, so slow growing seafloor animals still form dense communities across large areas.

Germany and partner nations have proposed designating roughly 850,000 square miles here as a marine protected area, an ocean zone with extra legal protection.

If approved, this Weddell Sea MPA would become the largest protected ocean area in the world and a key refuge for cold adapted species.

The newly documented nests count as structured breeding habitats, a category that international guidelines see as especially important for seafloor protection decisions.

By adding clear video evidence of these habitats in the western Weddell Sea, the research bolsters arguments that the proposed MPA is biologically essential.

Climate warming is already reducing sea ice in parts of Antarctica, which means more ice shelves will break up and expose long hidden seabeds.

These changes make it urgent to understand who lives in newly opened areas and how human activity might affect them.

Climate change and ice fish nests

During the mission, Lassie gathered more than 27 hours of video, enough to trace nest patterns along a winding path of seafloor.

The team plans to return with improved cameras and environmental sensors to track how the fish community responds over many breeding seasons.

“The entire community is a dynamic interplay between cooperation and self-preservation,” wrote Connelly in his commentary on the nests.

That perspective turns a field of shallow pits into evidence of social behavior, shaped by both cooperation and the constant threat of predators.

Each new look beneath retreating ice has the potential to reveal similar hidden neighborhoods, changing how people understand the deep ocean and its future.

The study is published in Frontiers.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–