Doctors successfully implant a pig's lung into a human for the first time

A team in China connected a gene edited pig lung to a man who had been declared brain dead. The lung worked for 9 days and moved oxygen into the blood before the immune system damaged it.

This is part of xenotransplantation, the use of animal organs to help people who need transplants. It matters because many patients die waiting for an organ that never comes.

The team reported the case in a peer reviewed study that followed the pig lung for 216 hours, which is 9 days. That timeline let doctors watch how a human immune system reacts to a pig lung over time.

The lead surgeon, Jianxing He of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, directed the operation and analysis. His group works in lung surgery and transplant research in Guangzhou, China.

In 2024, the United States performed 3,340 lung transplants, according to an OPTN report. Even with rising numbers, the waitlist stays long and the need is urgent.

Implanting a pig’s lung into a man

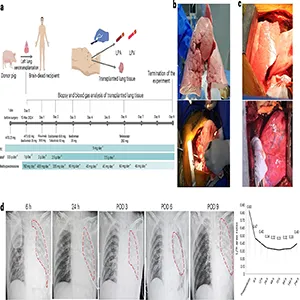

Doctors removed the left lung from a gene edited Bama Xiang pig (a small, traditional Chinese pig breed that scientists often use in xenotransplantation research because its organs are closer in size to human organs).

They attached it to a 39 year old man who had brain death after a severe brain bleed. The donor pig carried multiple edits made with CRISPR, a tool that changes DNA in precise ways.

Three pig genes that cause strong immune reactions were deleted, and three human genes that help control clotting and the complement cascade were added.

The lung was connected to the man’s airway and blood vessels using standard transplant techniques. The other native lung stayed in place so the team could keep the patient stable and collect data safely.

What worked and what failed

Right after blood flow returned, the lung exchanged gases. Measurements from the lung’s vein showed healthy oxygen levels, confirming basic function.

The worst early problem was swelling with fluid within 24 hours. That pattern matched primary graft dysfunction, a form of early lung injury that can follow any transplant.

On day 3 and day 6, tests showed antibody binding and complement activation damaging the tissue. By day 9, some measures looked better, but the team ended the experiment and removed the lung for study.

How the immune system reacted

The first threat in cross species transplants is hyperacute rejection, a rapid attack that can destroy an organ within minutes.

The gene edits and drug immunosuppression regimen prevented that early catastrophe in this case.

Later, the body made antibodies that stuck to the lung’s tiny air sac walls. Complement proteins then piled on, and the organ swelled and stiffened as inflammation built.

Swelling made the lung heavy and less transparent on scans. Compliance fell, meaning it took more pressure to move air, which is a bad sign for breathing mechanics.

Humans and pig lung transplants

A lung is an environment-facing organ that breathes air full of microbes and particles. It is loaded with immune cells that can wake up fast, and that intensity can flip from defense to damage in a new organ.

Blood vessel tone in lungs can also constrict when blood meets cells from another species. That raises vascular resistance, worsens inflammation, and quickly feeds fluid into air spaces.

Even in human to human operations, lungs fail more often than kidneys or livers. That built in fragility makes the road for pig lungs tougher than for other organs.

“This work is exciting as a first look at what happens when a pig lung is put into a human being,” said Richard Pierson III, a surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“This is a building block that is required for the field to incrementally advance,” said Justin Chan, a heart and lung transplant surgeon at NYU Langone Health.

Both comments point to steady work, careful trials, and no overpromising. The field needs measured steps and clear data before trying this in living patients.

What this means for patients

Recent results with pig kidneys in living people are encouraging. A man has lived more than six months with a pig kidney.

Lungs face different biology, so kidney progress does not transfer directly. Still, success in one organ shows that gene edits and drug choices can be tuned to control rejection for longer.

If researchers can find the right mix of edits and medicines for lungs, many lives could change. Patients with cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, or severe emphysema could get options that do not exist today.

What changes researchers will try next

Future pigs may include added human genes that better control clotting and inflammation in the lung’s capillaries. Targets include endothelial pathways that limit injury during blood flow restart.

Drug programs may expand to block B-cell and T-cell signals earlier and more strongly. Combinations that inhibit antibody production and complement activation together look promising.

Organ preservation and perfusion methods could also help the first hours after surgery. Reducing fluid overload and limiting inflammatory signals at the start may prevent the harmful spiral seen here.

How to read the results carefully

This case used one pig lung while the other human lung stayed in place. That design helped safety, but it makes it hard to judge the full work of the pig lung alone.

The man had brain death, which itself increases inflammation. That condition is not the same as a stable living recipient, so future trials must test both settings.

Nine days is both short and very informative. It gave a window into the timing of rejection and set a baseline for what the next round must overcome.

The study is published in Nature Medicine.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–