Scientists find evidence of 'smoke-dried mummification' of ancient humans

Archaeologists have identified human bodies preserved by “smoked mummification” in Southeast Asia, dating back as far as 14,000 years. The technique created mummies by subjecting the bodies to sustained heat and smoke, but not flames.

The pattern appears across multiple countries and suggests a deep, long-running tradition. It pushes mummification’s origins back thousands of years earlier than previously thought.

Hsiao-chun Hung, a researcher at the Australian National University in Canberra, noticed striking similarities between ancient remains excavated in Vietnam and living traditions in the region.

She and her colleagues examined dozens of hunter-gatherer burials from sites across Southeast Asia to test whether these people had been slowly smoked after death.

Their comparisons connect ancient practices with customs that persist in parts of New Guinea today.

Smoked mummies in West Papua

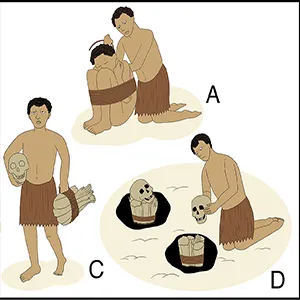

In West Papua, Indonesia, the Dani community still preserves the dead by smoking the body, then keeping and venerating the ancestors at home. Many are bound into tight, crouched poses.

Similar “hyper-flexed” postures show up throughout the archaeological record, with examples reported from Australia, China, the Philippines, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, South Korea, and Japan.

The resemblance gave researchers a modern analog for understanding how ancient caretakers might have achieved long-term preservation in humid landscapes where ordinary burials decay fast.

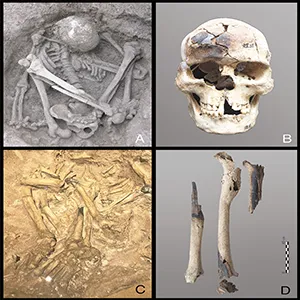

Clues hidden in ancient bones

The study focused on 54 burials from 11 archaeological sites, located primarily in northern Vietnam and southern China. The sites date to a period spanning roughly 12,000 to 4,000 years ago.

The researchers examined bones for microscopic and chemical evidence of gentle heating over weeks or months rather than burning.

More than nine in ten of the 69 skeletal samples they tested showed heat exposure consistent with smoking at low temperatures.

The pattern fits a process designed to dry, cure, and protect remains rather than to cremate them.

Smoked mummies older than Egypt

In the cave of Hang Cho, Vietnam, the team identified a smoked mummy over 11,000 years old.

At nearby Hang Muoi, they documented similarly singed, tightly bound skeletons dated to more than 14,000 years ago.

Those dates move the origin of mummification well before the famous Chinchorro of northern Chile, around 7,000 years ago. They also predate dynastic Egypt by a wide margin, around 4,500 years ago.

Smoke slows tropical decay

Smoking a body desiccates soft tissues, slows bacterial activity, and repels insects – key advantages in warm, wet environments where decay is rapid.

Binding the body into a compact, “hyper-flexed” pose may have helped with handling and transport, whether to bring the dead home or to reposition them for ritual.

Hung proposes that such bindings made remains easier to move within a mobile, hunter-gatherer world.

Smoked mummies found globally

Taken together, the evidence points to a broad, enduring tradition across southern China and Southeast Asia.

Hung’s team argues it stretches back at least 14,000 years and likely continued until about 4,000 to 3,500 years ago, when agriculture and new social arrangements became dominant.

The ethnographic record suggests echoes persisted much later. In southern Australia, similar practices were observed into the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Hung said that ethnoarchaeological studies in the New Guinea Highlands reveal that, in some communities, this practice still continues today.

Hyper-flexed smoking mummification

For communities that preserved their dead this way, smoking was more than a technique. It kept ancestors present as active members of the household. The continuity is striking.

According to Hung, the results show that a unique combination of technique, tradition, culture has persisted for an astonishing length of time and spread across a vast region.

Above all, these hyper-flexed, smoked-mummification burials suggest a deep belief in the afterlife and enduring love for the ancestors.

Where mummification began

The findings challenge the idea that early mummification began only in deserts like the Atacama or the Nile Valley.

Vito Hernandez of Flinders University noted that the study emphasizes the role tropical environments have played in fostering distinct mortuary traditions amongst early modern humans to have spread to the Far East and, potentially, the Pacific.

Seen this way, the tropics are not a barrier to innovation but a crucible for different solutions to the same problem: how to care for the dead and keep bonds with the living.

Smoking the dead redefined

By pushing the timeline back, the Southeast Asian record becomes central to the global story of mummification.

“By extending the timeline of mummification by at least 5,000 years before Chinchorro culture [of South America], they highlight Southeast Asia as an independent center of cultural innovation,” Hernandez said.

The result is a picture of independent invention, shared themes and enduring memory across thousands of years.

Creating smoked mummies may be one of humanity’s earliest preservation practices. It thrived in humid forests, linked households to ancestors and left a signature visible in bones and bindings today.

The science behind the claim is careful. The story it reveals is human.

The study is published in the journal Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–