Cave bones reveal the first humans in the Iberian Peninsula were already expert hunters

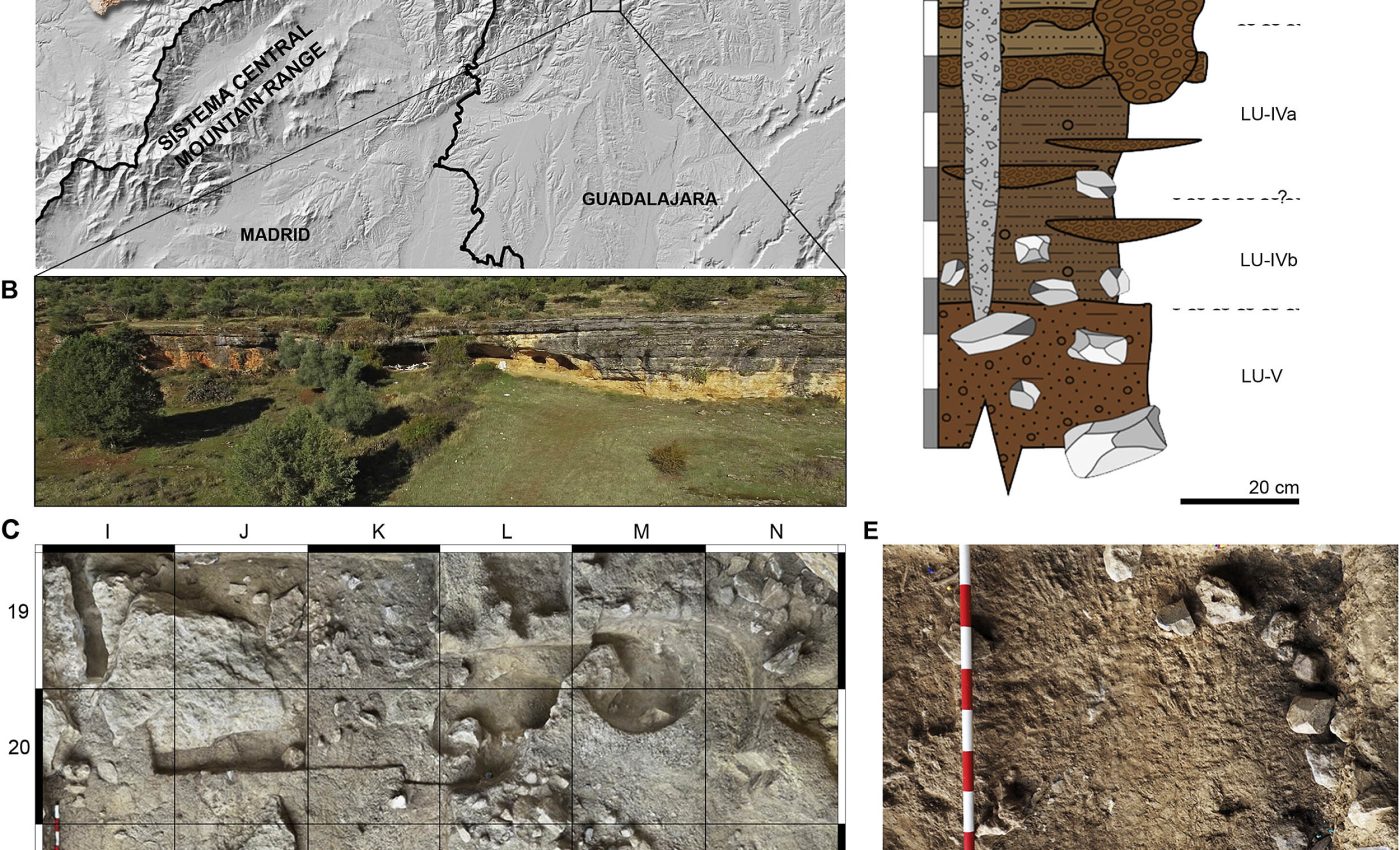

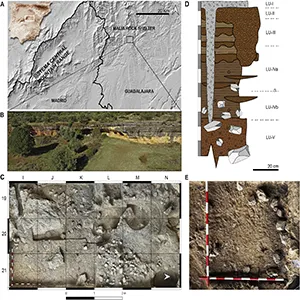

A new study of ancient bones from a small rock shelter in central Spain shows that the first humans who lived in the Iberian Peninsula were hunters, using the site repeatedly between about 36,200 and 26,260 years ago.

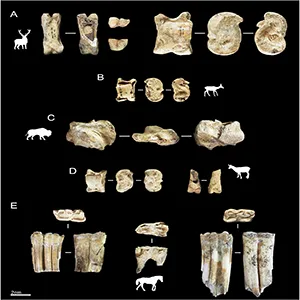

The animal bones they left behind point to careful hunting and butchering of deer, horses, bison, and chamois.

Lead author Edgar Téllez works at the National Research Center on Human Evolution (CENIEH). His team’s work helps fill a big gap in how we understand life on the Iberian Plateau during the early Upper Paleolithic.

The first humans in Spain

The faunal remains carry clear signs of human action, including cut marks on limb bones, percussion scars from breaking long bones, and patches of burning near hearths.

Those marks line up with brief visits tied to hunting trips, rather than long stays.

“The combined data suggest that the Malia rock shelter was used for short but recurrent occupations, likely by small groups engaged in hunting expeditions,” wrote Téllez.

The bones come mostly from ungulates, hoofed mammals that offer meat, marrow, fat, and hides.

Hunters focused on medium and large animals and processed them on site, then likely carried high-value parts away. That pattern fits a lean way of living that balances calories, tools, time, and risk.

Ancient bones in the interior

For decades, textbooks treated the interior of Iberia, the Meseta, as being almost empty during the first part of the Upper Paleolithic.

A new paper on the same rock shelter, however, shows repeated occupations of the first humans in this region of Spain at far earlier dates than many expected.

Coastal caves got most of the attention because they preserved well and were easier to find. Evidence from the interior changes that picture and pushes researchers to rethink where people settled and why.

Short occupations do not equal small brains or weak skills. They point to flexibility, knowledge of terrain, and the ability to plan for changing seasons.

Spain’s climate for the first humans

During Marine Isotope Stage 3 (MIS 3), climates swung between colder and milder phases.

Modeling work shows that shifts in plant growth and animal biomass affected when and where people could live, and that matters for inland Spain.

Lower productivity in parts of the interior would narrow windows for hunting large animals.

Even so, the Malia team documents repeated visits during a span of about 10,000 years, which points to human populations with know-how, patience, and a sense of timing.

The prey list matches a mosaic landscape of forests, grasslands, and mountains. That mix lines up with climate records that show changing water and vegetation resources in the region.

How archaeologists read ancient bones

Two fields, zooarchaeology and taphonomy, do the heavy lifting here.

Zooarchaeology studies animal remains to learn about past behavior, and taphonomy tracks what happens to bones between the time that animals die and the discovery of their remains.

Slice marks near muscle attachments, scrapes on metapodials, and notches on long bones are strong signs of butchery. Spiral fractures on green bone tell us that people broke limbs soon after death to reach marrow.

Burn patterns and charcoal patches show controlled fire use near small hearths. Together, these clues build a tight case for human hunting and on-site processing.

Other sites show pattern

Malia is not a lone data point in central Iberia. Peña Capón, another interior site, shows modern humans there by about 26,100 years ago, in cold, harsh conditions.

Short, task focused occupations also appear elsewhere in Iberia. Work at Cova Eirós in northwest Spain describes brief early Upper Paleolithic visits with faunal processing.

Those cases point to mobility patterns that link caves, rock shelters, and open camps across valleys and passes. People followed herds, water, and raw materials, returning to reliable spots when conditions allowed.

First humans rewrite Spain’s history

The Malia occupations span the Aurignacian and Gravettian periods (cultural labels tied to stone tools and bone points).

The early levels include Aurignacian bladelets and a single beveled bone point, while later levels fit Gravettian ages that trend colder and drier.

These dates matter because they overlap with swings in climate and habitat. They show that people did not wait for perfect weather, they learned to work with what was there.

The idea that the plateau sat empty until very late in human prehistory does not hold up under this evidence. It is better to see pulses of use that track resources and safe travel routes.

The inland hunters of central Iberia used sharp tools, fire, and careful planning, then moved on before local resources ran thin. That is a sensible way to live in a patchy landscape.

Their choices echo a broader theme in human history, which is adapting plans to changing limits. The lesson is simple; look closely at evidence, do not guess from gaps.

The study is published in Quaternary Science Advances.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–