'Lost world' of Arctic animals from 75,000 years ago has been discovered in a cave

A coastal Arctic cave in northern Norway has turned up an Ice Age animal community that feels both familiar and foreign. The bones point to an Arctic coast with birds, fish, and mammals living side by side about 75,000 years ago.

The team of scientists responsible for the find, cataloged 46 species from a single cave, and they show this was the earliest known animal community in the European Arctic during a warmer Ice Age pulse.

Animals found in the Arctic cave

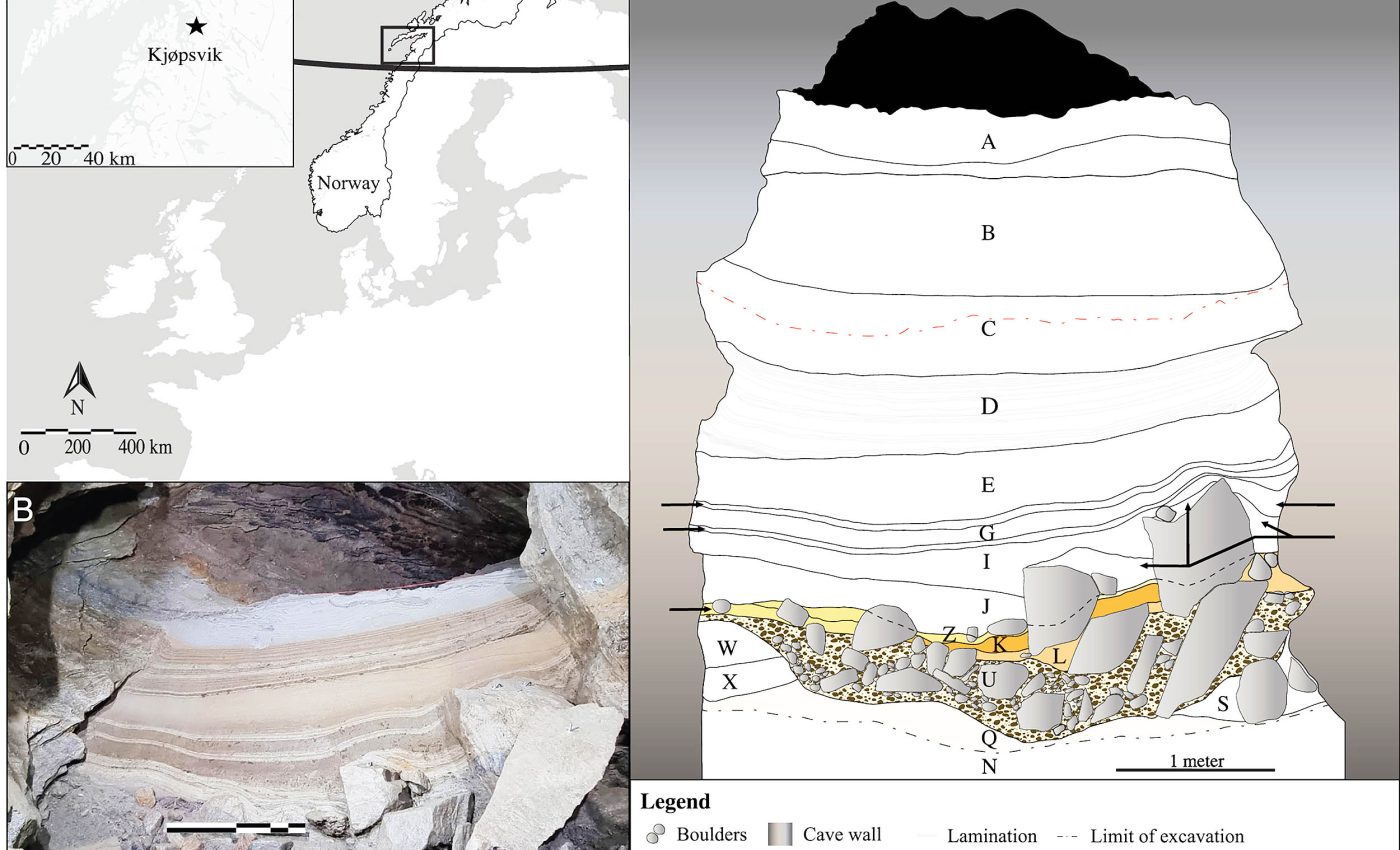

Dr. Sam Walker of Bournemouth University and the University of Oslo led the work. His team excavated Arne Qvamgrotta in 2021 and 2022, carefully sieving sediments for bone fragments.

Walrus, bowhead whale, and polar bear anchor the marine side, while rock ptarmigan, Atlantic puffin, and common eider speak for the birds. Freshwater and marine fish, including Atlantic cod and Arctic char, round out the picture.

Collared lemming appears in the mix, which is striking because it has not been known from Scandinavia before. That single line in the species list changes what we thought we knew about small mammals in the north.

The fauna points to a coast with open tundra nearby, freshwater lakes or rivers, and seasonal sea ice offshore. Together, the animals outline a working coastal ecosystem.

Understanding MIS 5a

Scientists place this window in Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5a, a warmer interval of the last glacial cycle between roughly 85,000 and 71,000 years ago.

MIS is a climate framework based on oxygen isotopes that tracks swings between warm and cold periods.

The dating comes from a blend of methods, including radiocarbon limits, luminescence on cave sands, uranium thorium on cave minerals, and genetic clocks on a subset of bones.

Each method has blind spots, so using several reduces the chance of a misread.

Decoding the Arctic cave animal bones

Most bones were tiny and shattered, which limits what experts can identify by eye.

The team solved that by mixing comparative osteology with metabarcoding, a DNA method that pulls short genetic tags from many fragments at once to identify the species list.

They also reconstructed a few mitogenome sequences to test how these animals relate to modern lineages. Those genetic trees placed several specimens on branches that do not survive today.

The cave layers show a community that moved in when glaciers retreated along the coast. When ice advanced again, the genetic lines represented in this cave did not track to new refuges, and they winked out locally.

That pattern fits what ecologists call a “lack of refugium use,” meaning populations failed to find safe pockets during later cold peaks.

For conservation, that matters because it shows how easily lineages can vanish even when a species persists elsewhere.

Sea ice, whales, and birds

Several mammals here rely on sea ice for key parts of their lives. A broad review of Arctic marine mammals shows how ice underpins feeding, breeding, and movement for bowhead whales and ice seals.

The bird list includes sea ducks and auks that thrive in cold, productive waters. That matches fish such as cod and golden redfish that prefer subarctic to Arctic shelves.

Warmer pulse in a cold age

MIS 5a was not balmy everywhere, but it was milder than the deep freezes that followed.

In northern Europe, repeated cycles of glacier growth and retreat reshaped coastlines, streams, and the animals that used them.

This cave, protected by the geometry of a karst system, kept a clean snapshot of one of those interludes.

The sediment story hints at periods of standing water inside the cave, then quieter times when bones accumulated between boulders.

“These discoveries provide a rare snapshot of a vanished Arctic world,” said Dr Walker.

The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979. That modern signal is clear in satellite and station analysis that compares regional trends to the rest of the planet.

If lineages could not keep up with colder swings in the past, fragmented habitats and rapid warming present a new kind of stress today.

Movement paths are cut by human activity, and not every coast offers a corridor to track changing conditions.

Learning from Arctic cave animals

Before this study, most high latitude records emphasized mammoth steppe megafauna. This cave shows a coastal community instead, with birds and fish documented alongside mammals.

That difference matters for paleoecology, the study of past ecosystems, because it fills a gap in early Weichselian history. It also shows how much we miss when bird and fish bones are too fragmented for standard methods.

Future work will likely expand the DNA record across more birds and fish to test how widespread lineage turnover was. Better reference genomes will allow tighter age estimates for more species.

Those steps can separate species that stayed from those that failed to track habitat. They can also show whether the coastal belt acted as a bridge or a cul-de-sac through repeated ice advances.

The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–