Archaeologists find 140,000-year-old human and animal remains at the bottom of the ocean

Off the eastern tip of Java, dredging barges dragged up more than sand. They pulled a piece of the past: a submerged river valley under the Madura Strait packed with fossils that had slept under fifty feet of water since long before the last Ice Age melted away.

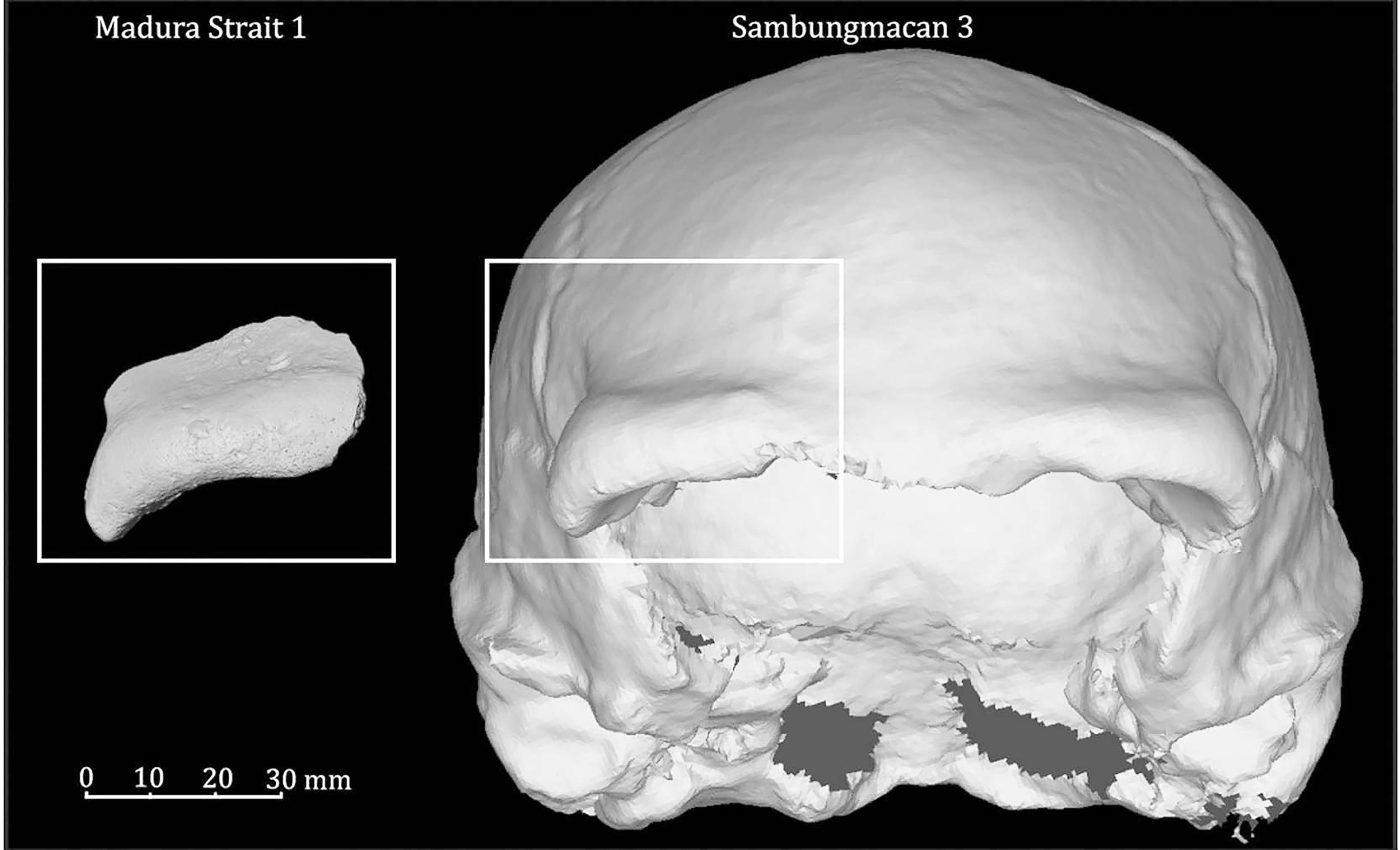

Among the finds were two skull fragments of Homo erectus, a human ancestor that roamed Asia until roughly 117,000 years ago, as well as more than 6,000 animal fossils that paint a vivid portrait of a lost ecosystem. Harold Berghuis of Leiden University leads the team studying the haul.

Sundaland rises then sinks

During colder glacial times, much of Southeast Asia’s continental shelf formed a single low‑lying continent known as Sundaland.

Sea level then sat about 400 feet lower than it does today, exposing wide plains crisscrossed by rivers and grasslands.

When global ice melted between 22,000 and 6,000 years ago, the ocean climbed roughly 443 feet, drowning half of that landmass.

The rapid pulses of rise carved islands out of peninsulas and pushed coastlines hundreds of miles inland, isolating plants, animals, and the people who depended on them.

Geologists can still follow the drowned river channels with high‑resolution sonar. Each channel marks a corridor that once connected Borneo, Sumatra, and Java to the Asian mainland, providing migration routes for both megafauna and hominins.

River fossils under the Madura Strait

The valley now mapped under the Madura Strait was carved by the ancient Solo River.

Optically Stimulated Luminescence dating (OSL) shows its sandy fill settled between 162,000 and 119,000 years ago, anchoring the new fossils to the late Pleistocene.

OSL works because quartz grains store energy from cosmic rays like tiny batteries. When technicians shine a laser on a grain in the lab, it releases that stored charge as light, revealing the moment the grain last basked in sunlight.

The method is ideal for underwater sites where radiocarbon fails, yet it is rarely applied because retrieving uncontaminated samples from the seafloor is difficult.

The Madura team’s success shows how pipeline spoil, often discarded as waste, can become forensic evidence on continental‑scale change.

Madura Strait reveals fossil menagerie

The tally of species rivals a natural‑history museum catalog. There were buffalo, several kinds of deer, and Komodo dragons longer than a canoe.

The biggest draw, though, is Stegodon trigonocephalus, an elephant‑like giant that could stand almost 13 feet at the shoulder.

Its presence suggests tall grass and open water holes, conditions that match pollen studies from upland Java.

Fossil monitors link today’s dragon‑patrolled islands to their mainland roots; remains of Varanus komodoensis have turned up on nearby Flores and Sumba, confirming that the apex lizard once ranged far beyond its present refuges.

Carnivore teeth in the assemblage are scarce, hinting that reptiles, not big cats, topped the food chain.

Antelope‑like bovids and open‑country rodents round out the scene, pointing to savanna rather than rainforest. Together the bones sketch a community more East African than Indonesian.

Humans with tools and strategy

Researchers counted more than 300 bones marked by stone blades or flakes. Some show percussion scars where marrow was pounded out.

“The Sunda Shelf played an important role in the dispersal and evolution of hominin populations,” wrote Berghuis and colleagues in their 2025 report. Others bear parallel slices typical of tendon removal.

“Thus far, hominin fossils from submerged Sundaland were not available.” The Madura Strait fragments break that drought. Underscoring the novelty of the find.

Tool cut geometry matches Acheulean‑derived technologies already known from Java’s terrestrial sites. That continuity supports the idea that people followed rivers seasonally, carrying simple gear that was easy to replace when tools were lost in mud or water.

What the skulls add to the story

Although each piece is only a few inches across, the brow ridge profile and bone thickness match late Homo erectus skulls dug from Ngandong and Sambungmacan farther up the Solo.

That link pushes the species’ confirmed range hundreds of miles east, showing it followed river corridors onto the shelf when sea level was low.

One fragment comes from an adolescent, the other from a lightly built adult. Their presence alongside butchered game hints that family groups, not lone hunters, roamed the valley.

Because no fire traces were found, the visitors probably camped on higher terraces that are now long submerged.

The bones they left behind washed into lower channels during seasonal floods and were sealed beneath overbank sand.

Looking for cousins beneath the waves

The Solo River was only one of many channels draining Sundaland. As survey vessels map more buried valleys, archaeologists expect to meet a wider cast: Denisovans, perhaps, or even the diminutive Homo floresiensis.

Every bucket of dredged sand now promises not just minerals for construction but clues to human origins.

Underwater archaeology once focused on shipwrecks; now it is turning to paleolandscapes that could double the search area for early humans in Southeast Asia.

The Indonesian government is drafting guidelines that will require sand‑mining companies to report fossil finds within 48 hours.

Those rules could transform commercial dredges into accidental research partners, expanding the data set at a fraction of normal field costs.

For now the Madura Strait cache stands alone, yet it already stretches the timeline of underwater archaeology in Asia.

Skulls, riverbeds, and giant beast bones, all locked together in a drowned landscape, remind us that today’s ocean floor was yesterday’s hunting ground.

The study is published in Quaternary Environments and Humans.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–