3D-printed food can turn waste into nutrition

Most of us want food that’s simple – fresh, close-to-home ingredients, meals that don’t cost a fortune, and produce that doesn’t spoil before we get to it. But the real world doesn’t always cooperate.

Many families live far from healthy grocery options, and nearly a third of U.S. food is lost each year to overproduction and waste.

At the same time, the foods that do reach our kitchens are often ultra-processed, engineered for shelf life instead of long-term health.

The big question becomes hard to ignore: how do we build a food system that actually works for people and the planet?

Reinventing how food works

Inside a lab in Arkansas, Ali Ubeyitogullari, a food engineer, has decided to attack that question from a surprising angle: 3D-printing food.

“We work at the intersection of food engineering and human health to improve people’s diets,” he said.

Ubeyitogullari grew up in Turkey around his family’s olive orchards in Antioch, but he did not dream of becoming a farmer or a chef. “Honestly, my parents were telling me they needed someone to pick the olives. I was like, sorry, I cannot help!”

When he later discovered at Middle East Technical University in Ankara that you could major in food engineering, he thought it sounded “super fun.”

Now, Ubeyitogullari is an assistant professor of food engineering with the Food Science and Biological and Agricultural Engineering departments at the University of Arkansas.

He is several years into a joint appointment and pushing 3D-printed food from science fiction into real experiments.

What 3D-printed food offers

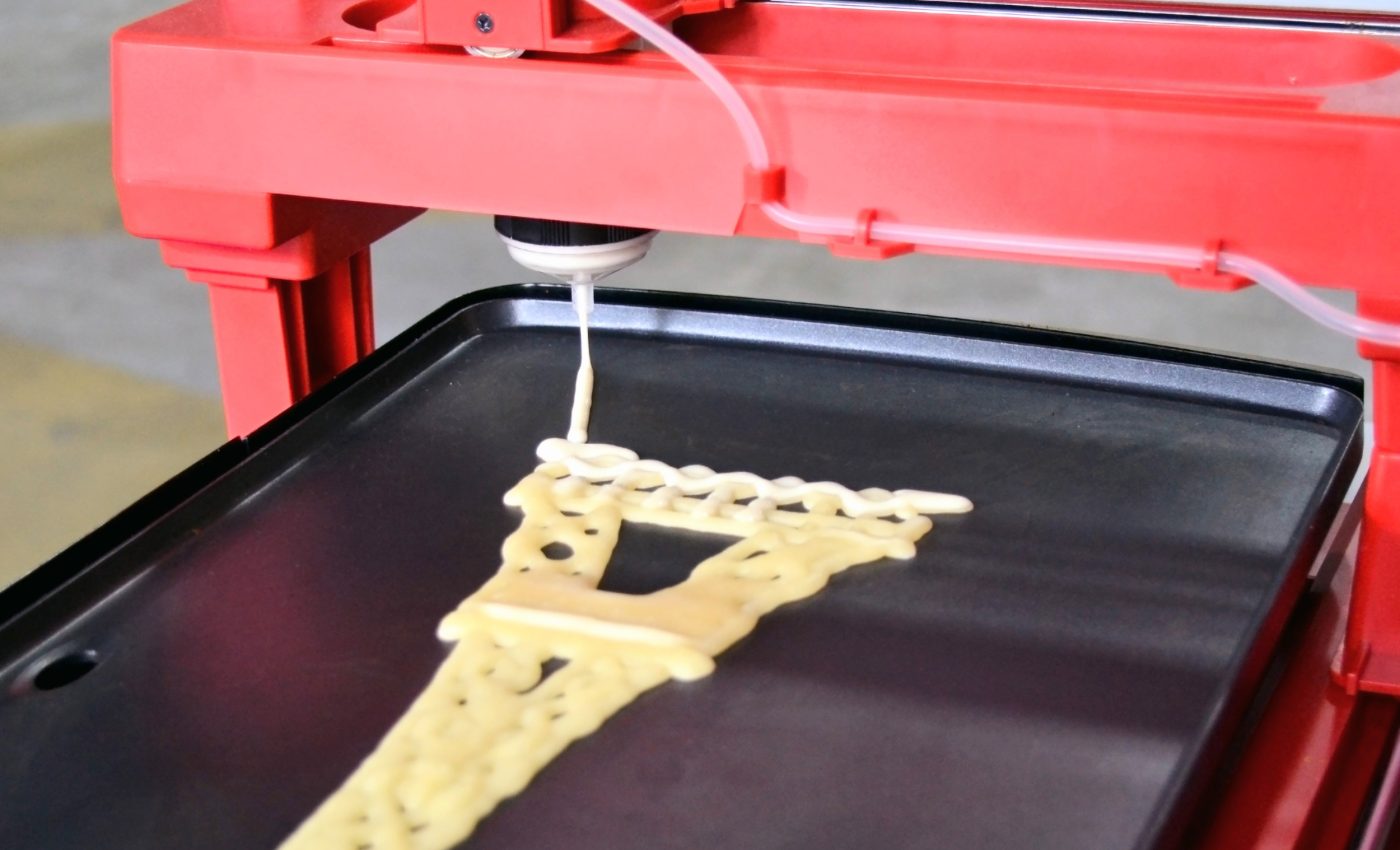

For many people, 3D-printed food sounds strange and even a bit unsettling, evoking images of industrial goo being squeezed out by machines.

The work in this lab looks very different. The idea is to use the same basic ingredients that go into regular processed food, but to assemble them layer by layer instead of pushing them through molds.

The science of 3D-printed food is far behind 3D-printed plastics or metals. Much of what this engineer is working toward may be at least a decade away in everyday life. Still, in the lab, Ubeyitogullari is already printing cookie doughs and flours.

Turning produce into bioinks

The “feedstock” for the printer can come from imperfect produce that shoppers usually ignore. An oddly shaped carrot can be freeze-dried, dehydrated, or blended into a slurry, then turned into a kind of edible bioink and squeezed through a nozzle.

Many children refuse vegetables, yet are more willing to eat them when they come in playful shapes. With software controlling the printer, bioink made from carrots or broccoli can become snacks shaped like SpongeBob SquarePants.

Chocolate bioink can turn into a Razorback mascot. This kind of flexibility uses up produce that might otherwise be thrown away and turns it into something more interesting.

Food shaped for swallowing

The work is not just about playful snacks. The lab also looks at dysphagia, a condition where swallowing becomes difficult. It affects an estimated 300,000 to 700,000 Americans every year and is more common in older adults, who often end up eating only soft, blended foods.

“You really lose your sense of food, like you don’t really understand from the puree what you are eating,” Ubeyitogullari said.

With 3D printing, the same soft, safe food could be reshaped to look like the original item, such as a piece of carrot or a slice of chicken, while keeping a texture that is easy to swallow.

That kind of change could make meals more recognizable and help people keep up their appetite and body weight.

Turning food into medicine

Because 3D printers run on software, shifting from one product to another does not require tearing down a factory line. You can swap cartridges of bioink and update a digital file.

That makes it easier to think about mobile printing setups that can travel to environmental disaster zones, humanitarian aid stations, or even space stations. Meals in those settings already rely on shelf-stable rations, similar to military MREs.

The key difference is that 3D-printed meals would not have to be identical for everyone. The nutrition profile could be tuned to a specific situation.

More calories and protein are needed for a soldier doing heavy work, special nutrients may help an astronaut manage muscle loss in microgravity, or fortified foods could be designed for a displaced person dealing with malnutrition.

Ultimately, Ubeyitogullari believes that personalizing nutrition will matter more than cutting costs or saving energy. The central idea is food-as-medicine, built into the structure of what we eat.

Smart edible materials

One major line of research in the lab focuses on bioactive compounds. These are chemicals that appear naturally in fruits, nuts, seeds, and vegetables.

The compounds are linked with a lower risk of cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, and they support general health.

Probiotics, such as those found in yogurt cultures, are living microbes that help keep the gut in balance. An increasing number of studies point to the gut microbiota and the gut-brain axis as important players in mood, mental health, and immune function.

The problem is that many of these compounds are fragile. They break down during storage and processing and have trouble surviving the gut to reach the places where they work.

“Their bioavailability is very low, so that when you consume them, you don’t really get the full benefit of them,” said Ubeyitogullari.

He estimates that because of low absorption in the gut and short shelf life, we absorb only about one percent of the bioactive compounds we consume.

Food that protects nutrients

Probiotic microbes often die in the acid of the stomach before reaching the colon, especially when antibiotics are involved. To protect them, his lab is testing probiotic microbes infused in an alginate-pectin material.

As one earlier description of this work put it, “Alginate is a seaweed extract and pectin is the gel in jellies. The alginate-pectin material is resistant to low pH (highly acidic) levels in stomach acids but will open in the less acidic levels found in the colon.”

This strategy is part of a wider process called encapsulation, where bioactive compounds are tucked into a stronger food matrix.

“We use different food-grade biopolymers – basically food ingredients commonly used every day in the kitchen,” said Ubeyitogullari.

“Mostly we’re interested in things that form hydrogels or gels because we want a porous structure. Starch, when you just mix it with water and heat it up, forms a gel.”

“It forms very nice porous structures so you can load them with bioactive compounds and, at the same time, when you do that encapsulation, you reduce the size of the compound but also physically protect it from the environment.”

Sorghum, starch, and smart gels

To build these edible structures, the lab tests ingredients that work both nutritionally and physically. Sorghum flour is one of them.

Sorghum is gluten-free, high in fiber and plant protein, digests slowly, and thrives in dry conditions. It already appears in meat substitutes and protein bars, and its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant traits make it useful as a bioink.

Ubeyitogullari is developing a new 3D-printable gel made from sorghum protein. In another project, researchers are testing ways to boost the bioavailability of two specific compounds in starch-zein gels for the first time.

One is lutein, associated with eye health. The other is a group of plant pigments called anthocyanins, associated with better visual and neurological health.

The team uses corn starch as the outer layer because it extrudes well and holds its shape. Zein, a hydrophobic material made from maize, forms the core layer.

The researchers adjust nozzle speeds and the percentages of starch and other ingredients to balance printability, texture, and nutritional performance.

3D-printed food at home

For all the talk of printers and bioinks, Ubeyitogullari does not argue that this technology should replace fresh fruits, vegetables, or whole grains.

The point is to offer better choices when produce spoils, work limits shopping, prices rise, or someone dislikes vegetables. Public opinion may be a bigger obstacle than the machines themselves.

“People thought the microwave was making Frankenstein foo – radioactive, this and that,” he said. “But now every home has a microwave. I think people will see that a 3D printer is just another kitchen tool to process food.”

Ubeyitogullari even anticipates a day when a person could use a smartphone to order a meal to their own kitchen, tweak the nutrition or medications in it, and have that meal waiting after work.

Whether that sounds exciting or unsettling, work in this Arkansas lab shows that the future of food is not a distant concept. It is already sitting on the lab bench, quietly printing its next snack.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–