Dozens of V-shaped stone structures discovered from 7,000 years ago remain a mystery

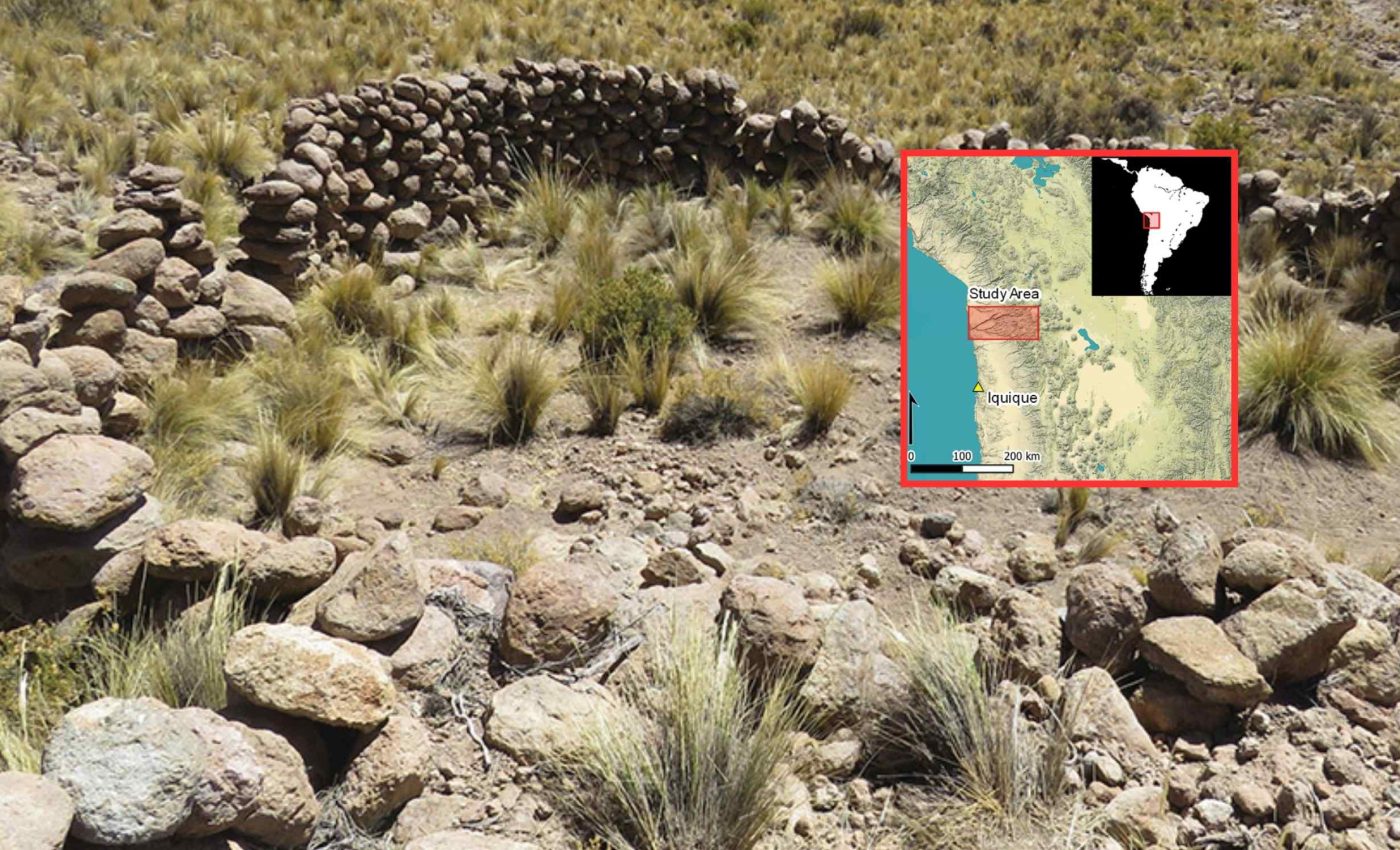

Seventy-six V shaped stone walls high in northern Chile are not just random ruins. A new study maps them as large animal traps that funneled herds into corrals.

The traps span about 1,790 square miles (4,640 square kilometers) in the Camarones River Basin. Together with nearly 800 nearby shelters, they show that organized hunting lasted far longer here than many textbooks claim.

What the trap walls reveal

Each V shape was built of dry stone walls about 5 feet (1.5 meters) high. The long arm often ran roughly 600 feet (180 meters), while the short arm averaged around 230 feet (70 meters).

This arrangement guided animals into a circular corral of nearly 1,000 square feet (93 square meters), with a drop of about 6.5 feet (2 meters).

The work was led by Adrián Oyaneder of the University of Exeter (UE). His mapping argues that hunters used these installations at least from 6,000 B.C.E. until the 1700s.

The team combined field checks with remote sensing, collecting data from satellites without using ground surveys. That approach helped them trace traps across steep slopes where paths vanish and wind strips away soil.

Traps tell a story of hunting

The layout of traps and hunter camps suggests foragers shared the highlands with herders and early farmers for centuries. That picture fits a pattern of blended livelihoods rather than one clean shift to farming.

Vicuñas were likely the main target. These camelids from the high Andes are small, quick, and form herds, which makes a funnel effective.

Today, their numbers hover between 460,000 and 520,000 across the Andes, according to a genetic analysis that also documents their recovery from severe 20th century declines.

Communal roundups have deep roots in the Andes. A broad review notes that past hunts gathered people at set times of year and that Inca-era roundups captured vicuñas for shearing, then released them alive.

Parallel inventions across continents

The Chilean traps echo a pattern seen far away. In the Middle East and Central Asia, archaeologists have catalogued more than 6,000 “desert kites,” which are long, low walls that once channeled fast-moving herds toward corrals or kill zones.

Independent solutions to the same problem do not require contact. “If you think about the shape of prehistoric fishhooks, you get similar solutions depending on the type of fish that you want to catch. The same happens with these traps,” said Oyaneder.

The Chilean traps share key features with kites found elsewhere. Most have two arms, a narrowing throat, and a final enclosure perched above a break in slope. These details help guide animals with minimal effort.

How the puzzle came together

Oyaneder first flagged the traps while scanning commercial satellite imagery. He found long lines on steep ground that converged, then ended at circular pens. This layout was hard to explain as corrals for domestic herds.

Field visits confirmed the pattern. Walls sit above gullies, the arms tighten downslope, and the final enclosure often follows the bedrock, signs of a design that is tuned to terrain.

To check scale, the study measured arm lengths and corral areas rather than relying on one or two examples.

The average long arm of near 600 feet (180 meters) and the short arm of near 230 feet (70 meters) reflect consistent planning across dozens of sites.

The traps cluster between roughly 9,000 and 13,800 feet (2,743 and 4,206 meters) above sea level. This is the same elevation band where wild vicuñas graze. That overlap strengthens the case that these were hunting installations, not corrals for flocks.

Why the traps matter now

These walls reframe how we think about ancient Andean economies. A strict story of hunting giving way to farming cannot account for landscapes threaded with traps and small camps.

They also show how patient scanning can transform what we know. Photogrammetry, building 3D models from overlapping photos, let the team document drops, wall courses, and enclosure shapes that are hard to see from the ground.

Seeing the traps in context matters for conservation too. Vicuñas recovered only with protection and careful shearing programs, and their story is a reminder that wildlife management is older than modern law.

The study closes with a practical plan. Oyaneder wants to apply machine learning – algorithms that spot patterns in data – to hunt for more traps in nearby valleys, a step that could reveal a far wider network.

Trap consistency indicates shared knowledge

Seventy-six traps across 1,790 square miles (4,640 square kilometers) sounds big. It is, but the count is almost certainly a floor, not a ceiling, because the Atacama’s winds erase shallow stonework over time.

Nearly 800 hunter shelters near the traps show sustained use, not one-off hunts. The spacing of those camps, and their position upslope or downslope from traps, sketch a travel rhythm tied to seasons and water.

The traps were not haphazard projects. Wall heights, arm lengths, and pen sizes vary within a narrow band, which implies shared know-how and some coordination among groups using the same valleys.

Some traps likely served more than hunting. Pens near springs would be ideal spots to sort animals for shearing, then release them, a practice that fits both the archaeological and historical record.

The study is published in Antiquity.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–