African wildlife populations devastated by war and conflict

Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park was one of Africa’s most impressive wildlife preserves, but since the 1970s, it has been ravaged by war. First, it was an anti-colonial war of liberation, which was then followed by a 15-year civil war. Both conflicts resulted in an extermination of over 90 percent of the park’s wildlife.

Researcher Joshua Daskin, a Princeton University graduate student in ecology and evolutionary biology at the time, was interested to see if African animal populations are consistently able to rebound after being exposed to war – as the Gorongosa populations had, or if they were more likely to completely collapse. He and Robert Pringle, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton, report their findings in the journal Nature.

Their findings reveal that war has been a consistent factor in the historical decline of large mammals in Africa. Populations that experienced stability in peaceful areas would experience a quick decline at even a slight increase of human conflict frequency. However, despite these downward trends, these populations rarely collapsed to the point where recovery was impossible.

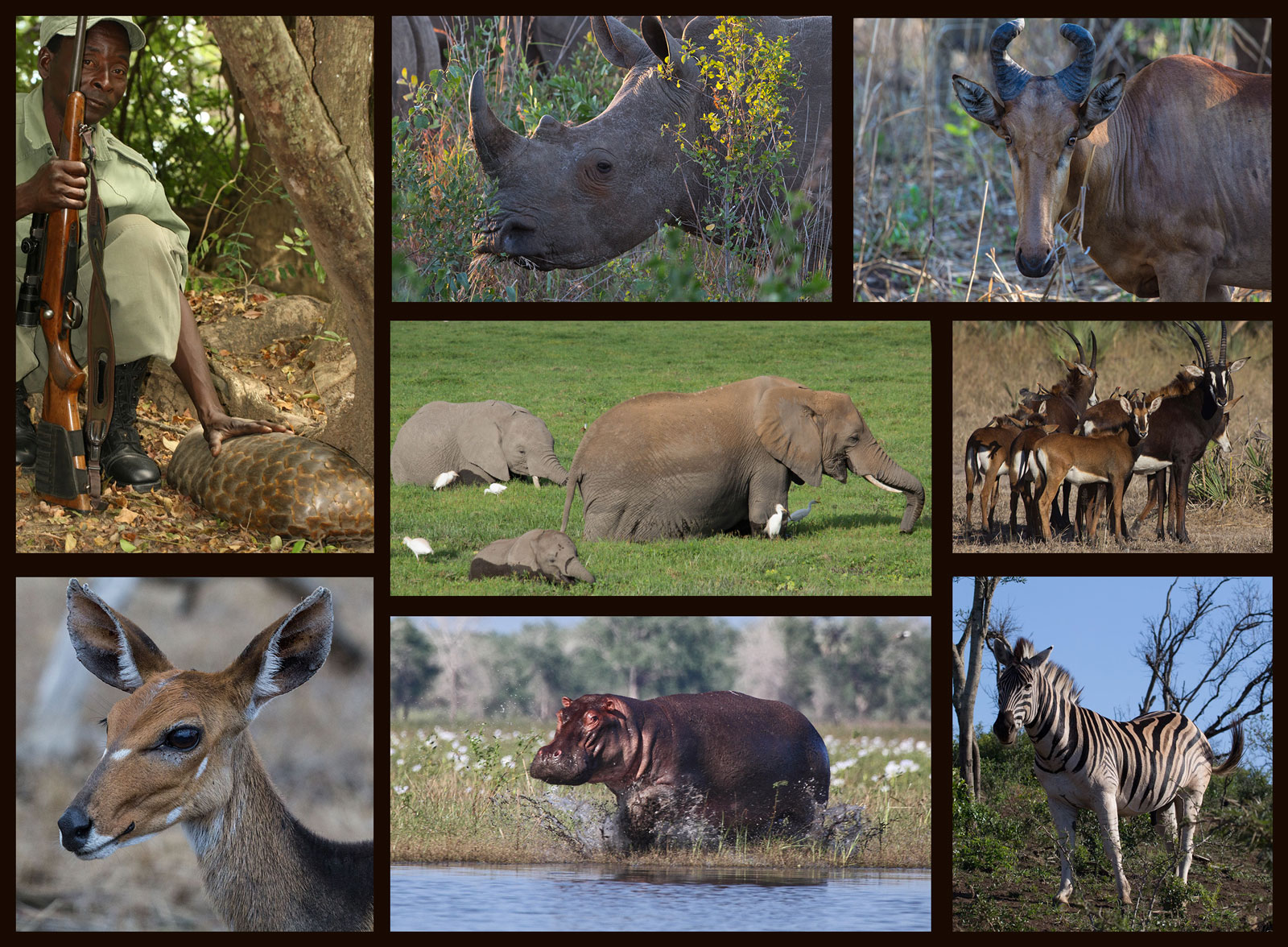

Between 1946 and 2010, more than 70 percent of Africa’s protected areas were touched by war. Large animals such as elephants, hippos, and giraffes experienced population declines as both combatants and hungry civilians hunted animals for meat and goods to sell, such as ivory. Despite this, Daskin reports that their study shows that even these severely affected areas are still promising candidates for conservation and rehabilitation efforts.

“We hope our data and conclusions will help in the effort to prioritize these areas for attention and funding from their governments and from international NGOs,” says Daskin, now a Donnelley Postdoctoral Fellow at Yale University. “We’re presenting evidence that although mammal populations decline in war zones, they don’t often go extinct. With the right policies and resources, it should often be possible to reverse the declines and restore functional ecosystems, even in historically conflict-prone areas.

Although it may seem obvious that war and human conflict would have a negative effect on wildlife, there have been some studies that show the positive effects of conflict on biodiversity. However, this study found that – with few exceptions – frequent conflict caused a downward trend among large-animal populations. “Most of the effects of conflict on wildlife populations seem to be due to knock-on socioeconomic effects that degrade the institutional capacity for biodiversity conservation, or the collective societal ability to prioritize and pay for it,” says Daskin.

Gorongosa was the park the originally inspired this study, and also exemplifies the study’s findings overall. In the early 2000s, the elephant population had dropped by more than 75 percent, and buffalo, hippo, wildebeest, and zebra numbers were thought to be in the single or double digits. But by 2004, wildlife in the park has rebounded to 80 percent of their total pre-war abundance.

“Our results show that the case of Gorongosa could be general,” explains Pringle. “Gorongosa is as close as you can come to wiping out a whole fauna without extinguishing it, and even there we’re seeing that we can rehabilitate wildlife populations and regrow a functional ecosystem. That suggests that the other high-conflict sites in our study can, at least in principle, also be rehabilitated.”

Although war and violent human conflict should obviously be avoided whenever possible – for our sake as well as the health of nearby animal populations – it’s at least comforting to know that its effect on wildlife may only be temporary, as long as the proper conservation and rehabilitation actions are taken after the conflict is over.

—

By Connor Ertz, Earth.com Staff Writer

Photos by Joshua Daskin, Yale University