Archaeological cave discovery upends the 'known' timeline of human civilization

Humans reached, settled, and thrived on Mindoro and other Philippine islands far earlier than most scientific timelines for allow for the evolution of human civilization.

These people did not wait for cities, farming, or metalworking. They learned the rhythms of reefs and tides and used the sea as part of daily life. This research supports that story with clear, measurable evidence.

The focus is on island living during the Paleolithic era, a time period when most scholars assumed long water crossings were out of reach.

The findings say otherwise. They show effective human migration, advanced technological innovation, and long‑distance intercultural relations at work in maritime Southeast Asia.

How humans reached Mindoro

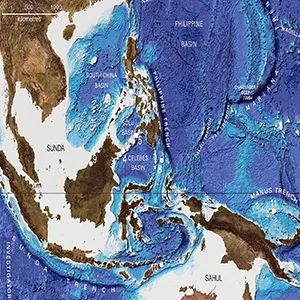

Mindoro, the 7th most populous island of the Philippines, sits along a natural route from mainland Asia through Borneo and Palawan. Anyone reaching Mindoro must cross water, including early humans.

That fact matters. It signals planning, basic seafaring, and an ability to manage travel between islands rather than relying on land bridges alone.

Scientists from Ateneo de Manila University, working with international experts and institutions, carried out the research. They built the case for the Philippine archipelago’s pivotal role in ancient maritime Southeast Asia.

Their study examines how early humans adapted to, and learned how to navigate, this marine setting with very limited technology and knowledge.

The team asks when they arrived, how they made a living on islands, and what relationship they built with the sea. Those questions guide the evidence that follows.

Discoveries in caves

Since about 2010, the team has systematically explored more than 40 caves and rock shelters in limestone terrain on Ilin Island and in the Sta. Teresa area of Magsaysay, Mindoro.

They recorded provenience (exact find spots) carefully, sampled sediments, and assembled a timeline from stacked layers.

Four sites stood out: Bubog 1, Bubog 2, Cansubong 2 Cave, and Bilat Cave. Each one preserves stratified deposits that track how people used the coast through time.

The cave layers hold cultural and biological remains that span approximately 35,000-40,000 years. That depth lets archaeologists trace change and continuity rather than rely on a single snapshot.

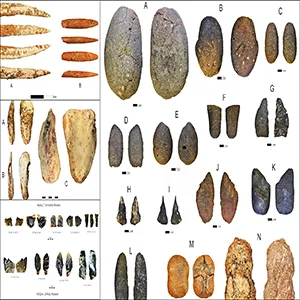

The deposits include shells from meals, bones of land and marine animals, and tools shaped from stone, bone, and shell.

Because the layers sit in order and dating methods anchor them, the team was able to show a sustained human presence on Mindoro rather than a brief visit.

Food, tools, and the sea

Diet reveals technology available to the early humans of Mindoro. Coastal layers show bulk harvesting of shellfish and other invertebrates, which matches what rich reefs and tidal flats can offer.

The faunal record also includes reef fish and pelagic species. Open‑water fish point to watercraft and gear suited for deeper water. That requires planning and repeatable methods, not chance scavenging.

“Advanced” in this context does not mean high‑tech gadgets; it means that people developed specialized, reliable systems to live with and from the sea.

Regularly catching open‑water fish, processing shellfish at scale, and adding land animals to the menu fit a flexible strategy that could handle shifting conditions.

Humans networking beyond Mindoro

Material patterns hint at social links. When similar tool types, processing methods, or coastal practices appear across separate islands, they suggest movement of ideas and skills.

The study situates Mindoro within wider maritime networks across Island Southeast Asia, with long‑distance intercultural relations dating back over 35,000 years.

These ties do not require preserved boats or written records. Consistent combinations of artifacts and food remains across places and times mark knowledge sharing. The sea connected communities rather than isolating them.

How the evidence holds up

Archaeologists documented each item’s exact location and layer, analyzed the surrounding sediments, and used radiocarbon dating to set ages.

They looked for repeated associations – shell heaps with particular fish species and distinctive tool forms – across multiple layers and sites.

Repetition strengthens the signal. When the same pattern appears across layers and sites, it supports long‑term behavior rather than a single event. The Mindoro record meets that test across independent contexts.

Evidence from Mindoro shows that maritime skills were not an afterthought. They sat near the start of the story for modern humans in this part of the world.

Demands of isolated island life

Even for modern humans, living on islands like Mindoro requires significant planning and unique skillsets. Resources fluctuate, storms reshape coasts, and sea levels rise and fall through time.

The Mindoro sequence shows communities who adapted to change by combining reef gathering, fishing that reached into open water, and hunting on land. That mix spreads risk and stabilizes supply.

Technology followed those needs. Stone, bone, and shell provided the raw materials for points, scrapers, and fishing gear.

Boats or rafts and the know‑how to use them enabled regular trips between shorelines and across channels.

Mindoro and the human timeline

The study challenges the idea that complex seafaring arrived much later in the evolution of human civilization.

To inhabit the islands at the times recorded in Mindoro, technological advances in seafaring – beyond what many scholars considered possible for the Paleolithic – were necessary.

The evidence shows that early humans somehow learned and adopted a mature, maritime lifestyle much earlier in history than the textbooks suggest.

It also reframes the Philippine archipelago as a central setting for ancient maritime Southeast Asia. By documenting a long sequence of coastal living and repeated crossings, the work positions the islands as active hubs rather than remote outposts.

Many questions remain

With a timeline that reaches into the Old Stone Age, new questions arise.

How did watercraft designs evolve to manage local currents and winds? Which fishing methods targeted pelagic species, and how did gear change with season and habitat? Can isotopic studies on shell and bone tie specific layers to wet or dry periods?

Taken together, the Mindoro record shows early humans who understood reefs, fish behavior, and tides, and who managed the logistics of life on islands.

They used reliable systems that tied land and sea into a single economy. They kept connections to other island groups and shared techniques over distance.

The portrait painted by this study rests on a layered archive, stratigraphy that holds together, and dates that anchor the story in an exact historical time period.

It presents a clear, human‑scale view of early seafarers who, in ways still unknown to science, made the Philippine islands part of a connected maritime world.

The full study was published in the journal Archaeological Research in Asia.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–