Archaeologists find a huge auditorium hidden for 2,200 years

Archaeologists uncovered a 200 seat Greek auditorium in Agrigento, on Sicily’s southwest coast. The structure stayed hidden for roughly 2,200 years within a gymnasium that doubled as a school.

The location and design point to a place where physical drills and public speech shared the same address.

The work was led by Monika Trümper, professor of classical archaeology at Freie Universität Berlin. Her research focuses on Greek urban architecture and the ways young citizens were trained.

Finding a Greek auditorium

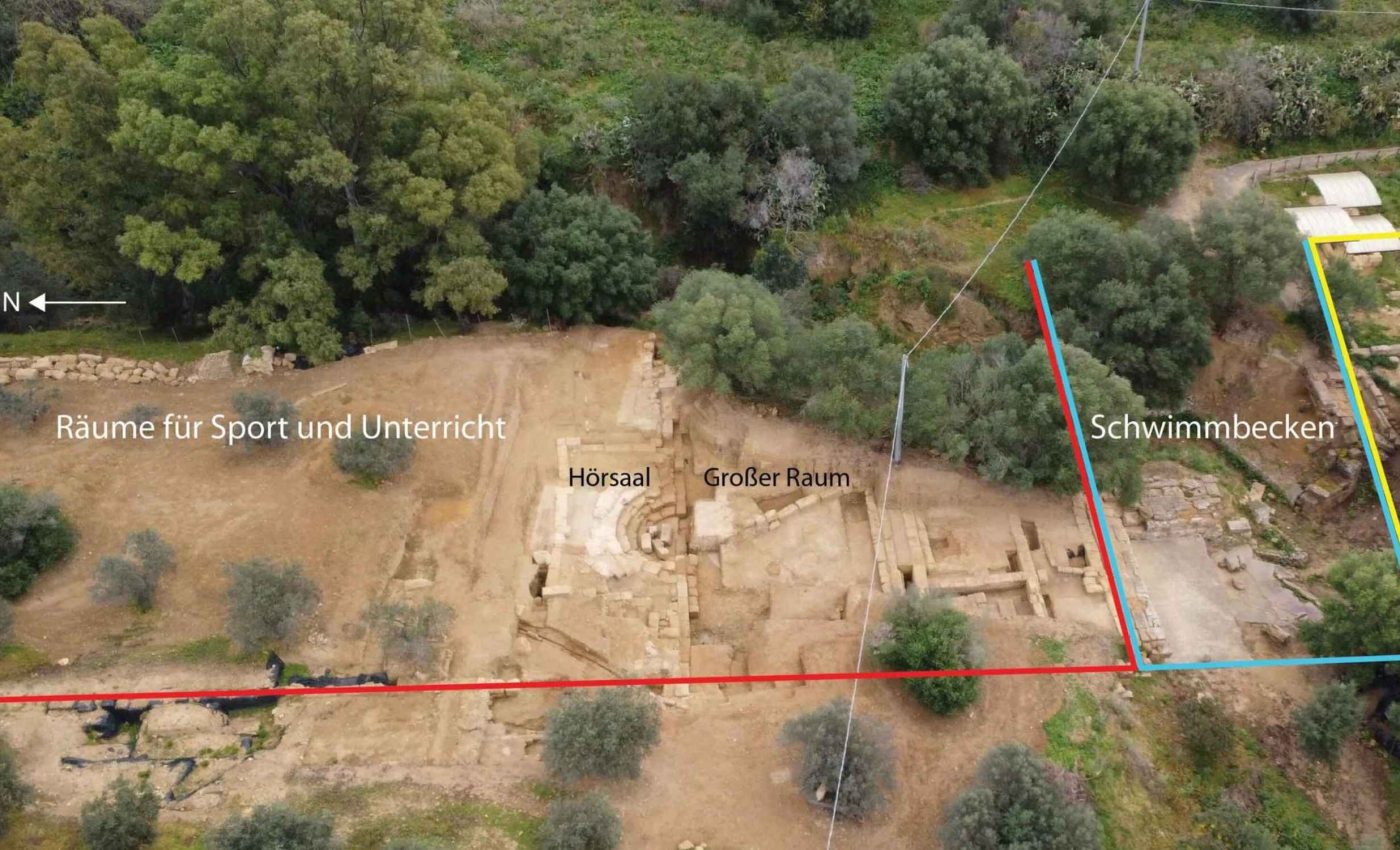

Excavators traced a semicircle of stepped benches built into the slope of the palaestra, open courtyard for exercise and instruction. The seating formed seven to eight tiers around a performance floor, with stairways for access.

The room measured about 23 by 39 feet and opened into a hall roughly 36 by 75 feet. The walls and benches were cut from calcarenite, soft limestone used widely in Sicilian buildings.

A wide doorway joined the benches to the larger hall so audiences could enter quickly. The floor in front of the seats was paved to steady speakers and students.

Survey and trenching also revealed two terraces that organized the court and rooms. The upper terrace sat about 13 to 16 feet above the lower one. The same campus already stood out for its 656 foot running tracks and a large pool.

Akragas as a school for citizens

A historian notes that among Hellenistic dynasties, the Attalids gave the strongest patronage to city gymnasia. That patronage turned these complexes into focal points for training citizens. It shaped how cities invested in spaces for young people.

In many cities, older teens entered the ephebate, year long civic and military training. They learned how to run, wrestle, and speak in public.

Gymnasia were civic engines where teenagers learned athletics, ethics, and argument. In a city like Akragas, that mix created a steady pipeline of public voices.

The auditorium’s shape fits lessons in rhetoric, law, and history. Students could test speeches, then listen to critiques that sharpened memory and timing.

Students would have trained on sanded courts, then filed into the hall for lessons. Teachers staged lessons, contests, and readings for an audience.

Unusual for a Greek auditorium

An official season report records the auditorium and its context. It notes that no other known gymnasium of the 2nd century BC held such a roofed auditorium.

It compares the space to an odeion, small covered theater for speech and music. The room functioned for lectures, performances, and competitions.

At Pergamon, a theater shaped lecture hall was added to the great gymnasium centuries later, in the mid 2nd century AD. That timing underscores how early Agrigento linked classroom speech to athletic training.

Elsewhere, similar semicircles tended to belong to city council buildings. Akragas had its own bouleuterion, council house for debate, in the civic center.

The find rewrites what we expect from western Magna Graecia, Greek settlements in southern Italy and Sicily. It shows inventive teaching infrastructure at the edges of the Greek Mediterranean.

With rows curving toward the floor, voices could carry without props. The adjacent hall with benches made quick transitions between display and discussion possible.

Reading the stones

Two inscribed blocks surfaced in the orchestra at the foot of the seating. One named a gymnasiarch and described a roof project funded by a citizen.

The text tied that private gift to the apodyterium, changing room for students and athletes. Letters traced in red spoke to dedications made to Hermes and Heracles in the late first century BC.

The stones had been reused in a later installation that cut across the floor. Parts of the inscription were damaged when walls were robbed centuries afterward.

Roof tiles stamped with Greek letters for gymnasium turned up in debris layers. They support the identification of the court as part of the same complex.

Greek civic offices and language stayed in use even under Roman rule. The gymnasium kept its role as the city’s training ground for youth.

Inscriptions from Agrigento are scarce across more than a thousand years. These lines sharpen the social life of a real campus, not just a ruin.

Learning from Greek auditoriums

Recent seasons have mapped walls, benches, and rooms that frame the auditorium and pool. A geophysical survey guided the first trenches and set the grid. That early work paid off when the auditorium appeared where hints had clustered.

The project brings together Italian and German institutions with student field schools. Cooperation keeps the site moving while training the next generation of researchers.

Work continues north of the auditorium where rooms cluster along a terrace. Researchers expect more classrooms and work spaces to emerge as the plan fills in.

Each trench extends the plan and clarifies how spaces worked together. The Agrigento team is assembling a full blueprint of education in stone.

Finds like this also feed practical training for students and early career archaeologists. The work unites careful measurement with a story that broad audiences can follow.

Image source: Thomas Lappi – Monika Trümper, © FU Berlin, Institute for Classical Archaeology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–