Oldest known human fingerprint found on first confirmed Neanderthal artwork

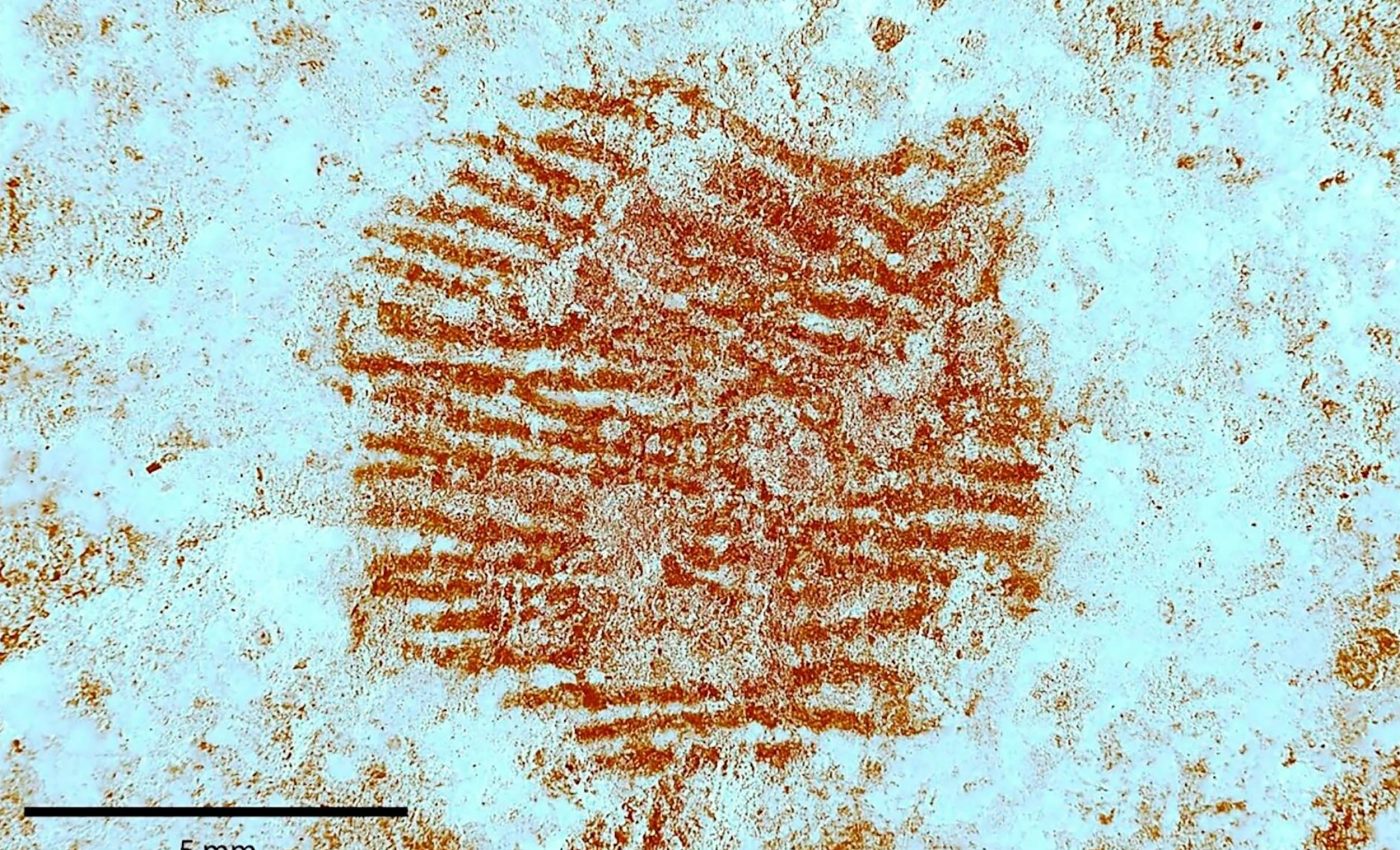

Archaeologists recently uncovered a pebble that appears to show the oldest full human fingerprint ever recorded. Their investigations suggest it was made by Neanderthals, who may have used a red pigment on a rock to shape what looks like an artistic rendition of a facial figure from roughly 43,000 years ago.

Curiosity grew when researchers noticed the pebble’s unusual shape and the red coloring placed where a nose might be.

Questions emerged over whether it was a random stain or if someone had placed the pigment there on purpose.

Professor María de Andrés-Herrero from the Complutense University explained that the team soon realized the mark was distinct from other stones, prompting a deeper look into the paint’s composition.

Neanderthal fingerprints and art

Researchers applied advanced imaging to identify whether the mark was simple residue. They found dermatoglyphic details, which refer to the ridges present in human fingerprints.

The imprint is thought to belong to an adult male who dabbed his finger on the pebble’s surface.

Experts ruled out accidental contact because the red pigment does not occur naturally in that location and appears specifically in the position of a nose-like feature.

These findings add new weight to discussions around Neanderthal creativity.

Studies indicate that communities of that era also painted cave walls and may have carried personal objects with symbolic markings.

Although most portable art is attributed to later populations, this new discovery suggests Neanderthals played a part in early artistic efforts.

Red pigment was placed on purpose

Some archaeologists initially wondered if the dot came from day-to-day tasks involving colored minerals. That explanation seemed unlikely because the pigment was deliberately placed and not randomly smudged.

Conclusive tests showed an iron-oxide-based compound consistent with ochre. An X-ray fluorescence analysis confirmed that the red hue was foreign to the shelter, implying someone brought it from outside.

A scanning electron microscope then revealed no other binding agents, supporting the idea that only natural pigment was used.

Neanderthal art shows early creativity

Neanderthals have long faced questions about their capacity to think symbolically, but fresh data from multiple excavations is broadening that view.

Earlier signs of symbolic behavior include shell collections, pierced animal teeth, and possible use of pigment.

This pebble from Segovia suggests Neanderthals may have marked objects with personal or communal meaning.

Archaeologist David Álvarez Alonso believes the red dot’s strategic placement hints at an intentional choice.

The entire rock was uncovered in a layer dated to the late Mousterian period. The occupant or occupants likely selected it for a reason unrelated to practical uses like pounding or cutting.

Unique identification details

Once the fingerprint’s presence was confirmed by digital imaging, forensic specialists studied its ridge patterns. These ridges gave clues about the individual who made the mark.

Officials relied on modern comparative methods and concluded that although it aligns with male characteristics, there is no absolute way to confirm species-specific traits because no Neanderthal reference prints exist in modern databases.

Spanish official Gonzalo Santonja described the pebble as “the only object of portable art painted by Neanderthals,” at a news conference updating locals on the find.

The designation of “art” sparks debate, yet researchers argue that marking a found object suggests some level of abstract thinking.

Why Neanderthal art matters

Many scientists now consider Neanderthals capable of symbolic thought. Their tool sets varied across regions, and some shaped pigments into lumps or used them for body decoration.

Although modern humans still produce the most recognizable forms of Paleolithic cave art, sites across Europe demonstrate that Neanderthals applied ochre in ways that go beyond simple functionality.

Experts hope that as more pieces turn up, the broader picture of these ancient populations will continue to evolve.

The close examination of this rock has already prompted rethinking about how creativity might have manifested in everyday Neanderthal life.

Still so much to learn

There may be disagreements over how to define art in prehistoric contexts, yet scholars increasingly see variety in Neanderthal expression.

Specialists suggest that this Spanish pebble fits into a growing collection of objects that highlight personal agency and symbolic awareness in the distant past.

Scientists caution that a single discovery rarely changes scientific consensus overnight. Still, the Spanish find is poised to spur ongoing study of subtle cues in future Neanderthal excavations.

The presence of a deliberately placed pigment and a clear imprint is a strong indication that these individuals viewed their surroundings in complex ways.

“The pebble from San Lázaro rock-shelter presents a series of characteristics that render it exceptional. It represents the first known pigment-marked object in an archaeological context,” said Andrés-Herrero at the end of an assessment with her team.

This view reinforces the idea that Neanderthals participated in artistic ventures once thought to belong solely to more recent humans.

The study is published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–