Astronomers capture the 'invisible' corona of a black hole located 6 billion light-years away

Astronomers have found a way to measure the hot corona around a distant supermassive black hole. The black hole sits in the quasar RX J1131, about 6 billion light years from Earth, and it glows with intense energy as it pulls in nearby gas.

Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the team watched how the black hole’s signal changed over several years. Those subtle flickers revealed the size and brightness of the gas halo.

This approach turned a distant quasar into a natural experiment on black hole physics and offered a rare look at conditions near one of the most extreme objects in the universe.

Invisible edge of RX J1131

The work was led by Matus Rybak, a senior researcher at Leiden University in the Netherlands. His research focuses on the hot gas and magnetic fields that surround actively feeding supermassive black holes.

Around RX J1131 lies a corona, a cloud of extremely hot, thin gas just outside the black hole. In this zone, particles are heated to millions of degrees and glow in high energy X-rays and low energy radio-like light.

The whole system shines as a quasar, a very bright galaxy center powered by a feeding supermassive black hole. As the black hole pulls in surrounding gas and dust, that material releases huge amounts of energy, across the spectrum, before falling in.

Gravity becomes a natural telescope

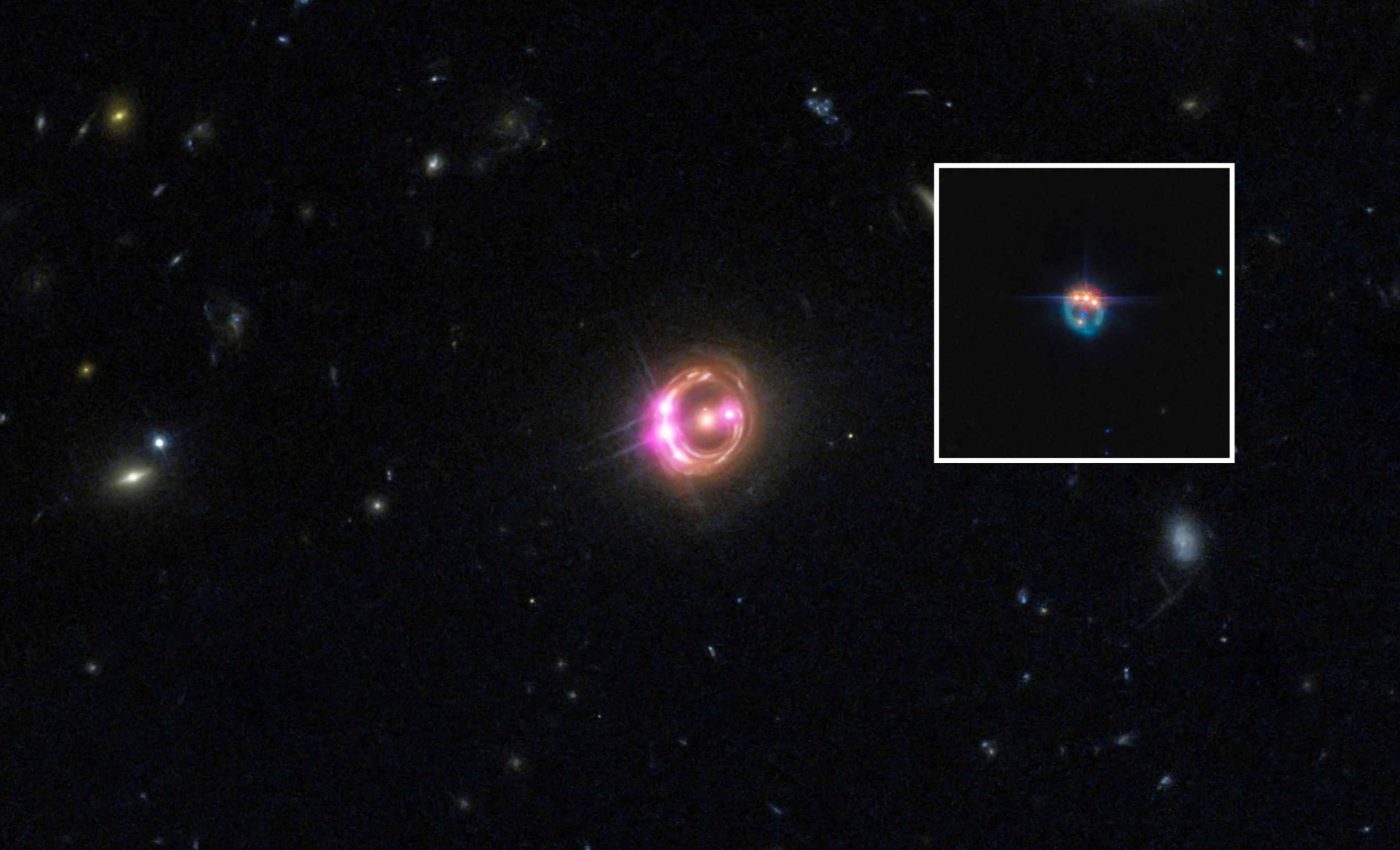

Between Earth and RX J1131 sits a galaxy that causes gravitational lensing. This phenomenon occurs where a foreground mass bends the light from a distant source.

These observations split the quasar’s light into four images around the lensing galaxy, each taking a different path through space.

Individual stars inside the lensing galaxy create an extra effect called microlensing. This is where a single star briefly acts like a tiny magnifying glass.

As the background light drifts behind different stars, small patches near the black hole get singled out and boosted in brightness.

Together, strong lensing by the whole galaxy and microlensing by its stars act like two stacked zoom lenses. That rare alignment sharpened the view of the corona. Such resolution would normally be impossible, even with our most powerful telescopes.

Solar system size corona

Rybak’s team examined older ALMA observations and paired them with new data. Within a few days of reviewing the material, Rybak noted that the patterns did not look right and warranted a closer look.

If the brightness changes had come from the quasar itself, all four images would have brightened and dimmed together. Instead, each one flickered on its own. This was a clear sign that tiny lenses inside the foreground galaxy were picking out different parts of the source at different times.

Using detailed analysis of those flickers, the researchers concluded that the light came from a very small region beside the black hole. They found that this region emits millimeter wave radiation, light with wavelengths around a millimeter.

From the strength of the microlensing, they estimated that the emitting zone is about 50 astronomical units across. That span is roughly the distance from the Sun to the icy outer edge of our solar system.

Magnetic fields and black holes

The new size measurement supports the idea that the corona is a compact region shaped by strong magnetic fields. Earlier theoretical work suggested that long wavelength emission in radio-quiet quasars can arise in this zone, rather than from star-forming regions or a jet.

The combination of millimeter brightness and X-ray power in RX J1131 lines up with the Gudel Benz relation. This is a pattern linking radio and X-ray output in magnetically active stars. Seeing the same balance in this quasar strongly favors a coronal origin for the long wavelength emission.

Millimeter light from radio-quiet quasars was once thought to change very little over time. Recent X-ray monitoring of RX J1131, however, reveals changes close to the black hole. Studies can match that behavior to the measured corona.

Lessons from RX J1131

ALMA is expanding into lower radio frequencies where black hole coronas glow brightest. This will enable astronomers to use microlensing tricks on many, more distant systems.

Each new flicker they catch will help map out how these extreme environments are structured and how their magnetic fields move energy around.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory will image the sky deeply and often, likely uncovering thousands of new lensed quasars similar to RX J1131.

Even if budgets for X-ray missions shrink, combining these optical searches with millimeter observations will keep revealing what happens just outside distant black holes.

The study is published in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–