Autonomous ocean glider will circle the Earth in historic mission

A sleek, carbon-fiber glider named Redwing slipped from a dock at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and headed for open ocean. If all goes to plan, it will not return for years.

Built by Teledyne Marine and operated in partnership with Rutgers University, Redwing is designed to become the first autonomous underwater vehicle to circumnavigate the planet. The journey is expected to last five years.

“This is a truly historic mission,” said Brian Maguire, Teledyne Marine’s chief operating officer. “It will pave the way for a future where a global fleet of autonomous underwater gliders continuously gather data from the oceans.”

The payoff, he added, will be early warnings of extreme weather and sharper climate projections.

Redwing glider has no propellers

Redwing is a next-generation Slocum Sentinel Glider, a descendant of the pioneering undersea vehicles invented by the late Doug Webb.

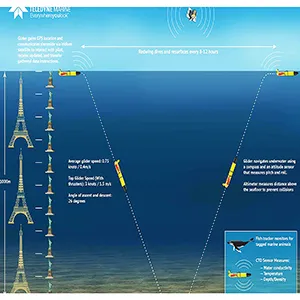

Unlike torpedo-shaped robots that rely on propellers, Redwing travels by subtly changing its buoyancy. It takes on or expels small amounts of seawater to sink and rise, converting that vertical motion into forward glide with stubby wings.

The result is a slow, ultra-efficient zigzag through the water column that can stretch a single deployment to a year or more.

Teledyne’s upgrades – larger frame, more battery capacity, and stronger communications – extend that endurance even further.

“This glider has the endurance and energy to do more than any other vehicle could,” said Shea Quinn, Teledyne’s glider product line manager and mission lead. “It’s designed to stay out there for a year or two at a time.”

Following Earth’s ocean currents

Redwing’s first act is to catch the Gulf Stream south of Martha’s Vineyard and surf it toward Europe.

From there, it will head south to Gran Canaria and onward to Cape Town, to further cross the Indian Ocean to Western Australia and New Zealand.

Next, it will traverse the Antarctic Circumpolar Current – Earth’s most powerful current – toward the Falkland Islands. Depending on conditions, the glider may tag Brazil and the Caribbean before closing the loop.

That routing isn’t just scenic. It threads Redwing through the ocean’s major highways and climate engines, where small shifts in heat and salt ripple outward to shape weather on land.

“We live on an ocean planet,” said Oscar Schofield, who co-leads the mission at Rutgers with fellow oceanographer Scott Glenn.

“All weather and climate are regulated by the ocean. This mission will give us another tool we need to achieve real understanding.”

Tracking the ocean’s pulse

Redwing carries a streamlined sensor suite that measures temperature, salinity, and depth. These are the basic variables that reveal how the ocean stores heat, moves it around, and exchanges energy with the atmosphere.

By diving and climbing through the water column, the glider builds a 3D picture of changing layers and fronts. These features can intensify hurricanes, drive marine heat waves, or shift fisheries.

Every eight to twelve hours, Redwing will surface, aim an antenna at the sky, and beam back data by satellite.

If a connection fails in rough seas or bad weather, the glider simply continues on its preplanned route and checks in later.

The glider’s built-in acoustic receiver will listen for tagged fish and marine mammals. These detections will reveal rare details of long-distance migrations in the open ocean.

Redwing glider as a student project

Rutgers students have shaped the Slocum glider story for decades – most notably in 2009, when the university’s Scarlet Knight became the first underwater robot to cross the Atlantic.

Redwing extends that tradition. Over 50 undergraduates are enrolled in a hands-on research course taught by Glenn and Schofield.

The students will develop flight tools and navigation aids, track the ocean glider’s progress, and publish field reports and explainers for a public audience.

The educational footprint stretches far beyond New Jersey. As Redwing reaches various continents, classrooms in those regions will join virtual sessions, swap stories and culture, and even exchange letters with Rutgers students.

The goal is a global cohort that follows a single instrument’s data trail while learning how the ocean works.

Pushing ocean tech forward

The mission’s name – Redwing, short for Research and Education Doug Webb Inter-National Glider – nods to Rutgers’ scarlet colors.

The name also memorializes Webb, whose motto, “Work hard, have fun, and change the world,” is stamped into the project’s ethos.

Webb began his career at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), where Redwing will begin its journey.

Today WHOI runs one of the world’s largest glider fleets, using them for climate research, endangered species protection, and real-time ocean observing.

Scott Glenn, a distinguished professor at Rutgers, sees Redwing as both an engineering milestone and a proof of concept.

“We’re deploying a robot that will travel the world’s oceans, gathering data,” he said. “And we’re doing it with students, educators, and international collaborators every step of the way.”

Continuing a record-setting journey

Fifteen years ago, Scarlet Knight logged 7,300 miles (11,748 kilometers) in 221 days, dodging ships and storms to land in Baiona, Spain, where Columbus’s fleet once returned from the Americas.

Redwing’s goals are more ambitious: a planet-spanning loop through the currents that underpin Earth’s climate.

If it succeeds, Redwing won’t be an outlier for long. Teledyne and Rutgers envision a global fleet of long-endurance gliders – quiet, persistent watchers that turn the ocean’s vast, under sampled interior into a living, measured system.

The ocean has always been our planet’s memory and thermostat. With missions like this, we’ll read it in finer detail, and teach a new generation how to do the same.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–