Canada passes bill to protect whales and dolphins from the cruelty of captivity

There are currently at least 2,360 cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in captivity worldwide, according to estimates by the Change for Animals Foundation. Since the 1950s, more than 5,000 cetaceans have died in captivity.

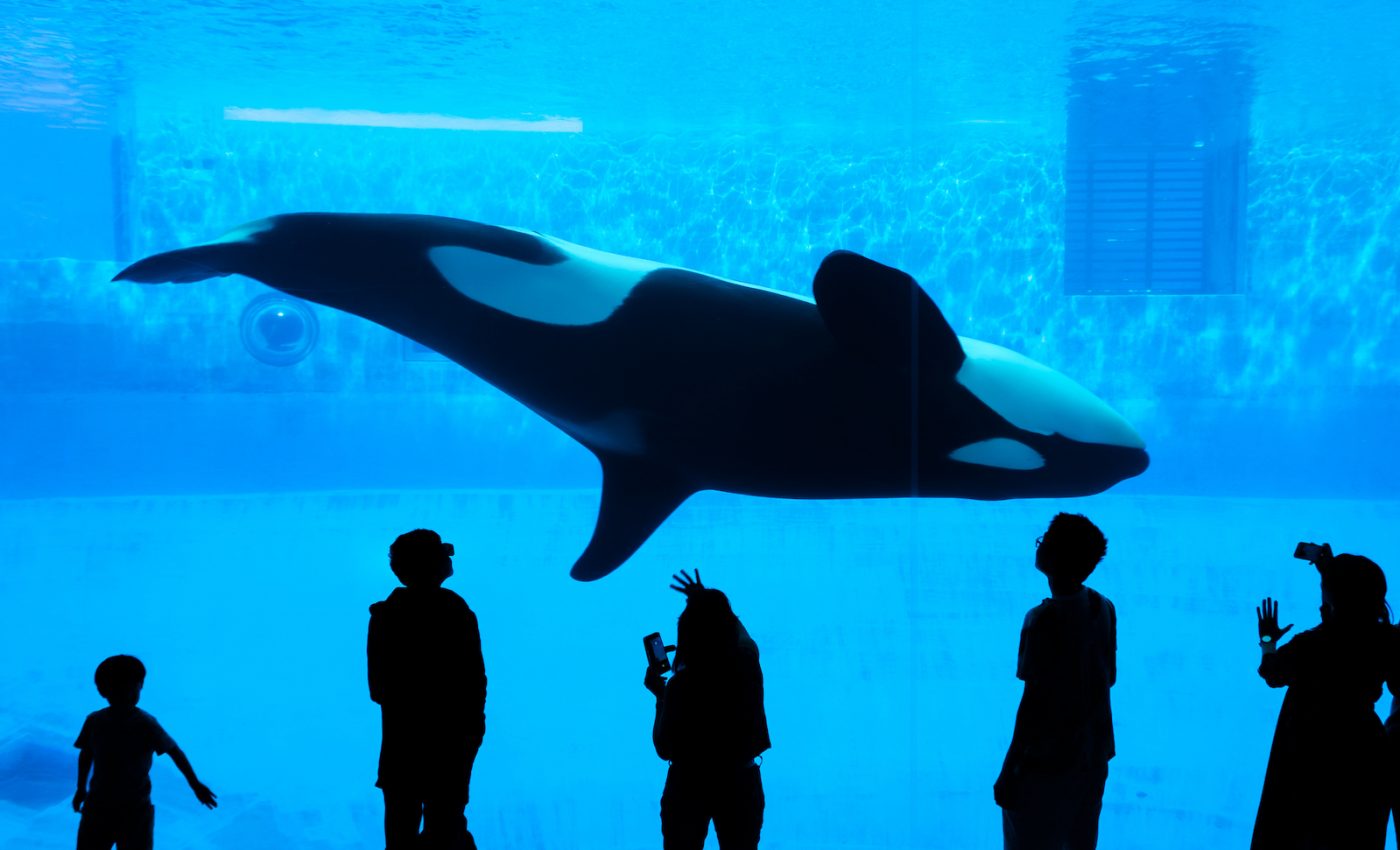

Captive cetaceans and other sea life are big business, bringing in millions of tourists each year to gawk at the acrobatics or sheer natural beauty of whales and dolphins. The documentary Blackfish and a growing public concern over the wellbeing of captive dolphins, orcas and whales has put a dent into businesses like SeaWorld, but the demise of captive cetacean entertainment is still far off. The Los Angeles Times reported in 2018 that more than 3.2 million people visited SeaWorld during the first three months of that year, reversing a downward trend in visitation and profit. Despite the ongoing controversy of keeping cetaceans in captivity, no laws in the US really limit the keeping or capturing of many cetaceans for shows open to the public or for research.

World Animal Protection reports that it is still legal in the US to capture wild dolphins with a permit. No permits for capture have been issued in the US since 1989, but this is largely because a large number of whale beaching has supplied dolphins kept in captivity instead. It’s still perfectly legal to capture dolphins with a permit.

Even the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 stipulates that dolphins and other marine mammals may be captured with the proper permits. Along with permits for capture, there is a 30 day period open for public objections to issue a capture permit and facilities must meet basic requirements for captivity of the marine mammals in question. Some contend that animals like orcas, dolphins and whales are too large or require too much space to ever be adequately cared for in captivity. No additional permit is required for a facility to export a captive cetacean to a foreign zoo or aquarium. This lack of substantial regulation of captivity for large and potentially dangerous animals leaves the industry open for criticism.

The Humane Society paints a bleak picture of captivity for cetaceans. The organization points out that captive facilities purport to give their animals good lives, partially by removing them from the ‘rigors’ of the wild, however these are rigors these animals evolved with. Lack of opportunities to travel long distances or to hunt and a change in normal mating and other social behaviors are part of captivity for cetaceans. These forced changes in behavior lead to stress-related conditions, and captive cetaceans develop ulcer, mutilate themselves and are abnormally aggressive. Mortality rates for orcas in captivity are also higher than in the wild.

All of this leads to a distorted view of these wild animals by the public that comes to view them in their cages, undermining what many of these organizations bill as education. Despite a slowly changing public opinion and the outrage expressed by animal organizations like the Humane Society, the US government has been slow to change any laws regarding cetaceans or other marine mammals in captivity.

Canada’s government is another story. Last October, Canada’s senate passed bill S-203 that would make illegal holding cetaceans in captivity or breeding them. The bill was first introduced in 2015 by a now retired senator and had the backing of Canada’s Green Party. The bill was vocally opposed by Canada’s Marineland, a popular marine theme park that currently holds 61 captive cetaceans. After years of debate and pushback from some conservative senators, the bill passed the senate last year.

Now, the bill has passed Canada’s House of Commons and has almost become law. All that stands in the way of the bill becoming law is royal consent, merely a formality in modern times. The bill has been hailed as Canada’s ‘Free Willy’ law, based on the 1993 movie where a young boy frees an orca from captivity. Animal rights groups have been thrilled with the new law and the progress it represents. The new law was also celebrated by Green Party leader Elizabeth May in a speech, calling it a ‘really good day for animals in Canada’, CTV reported. Marineland for its part says it will abide by what will be the new law. For now, parks that already exist, like Marineland, will continue to operate as the law grandfathered them in.

When law, the bill will punish violators will fines of up to CAD $200,000 (roughly US $150,000). Animals kept in captivity during rehabilitation are also allowed by the bill.

Some groups celebrating the bill want the Canadian government to go further and not grandfather in the existing marine parks, and instead outlaw all captive marine mammal parks now. One Green Planet reports that Marineland has a checkered history. SeaWorld once sued Marineland for the return of an orca lent them for breeding due to a decline in the orca’s health. In 50 years of operation, 17 orcas, 25 belugas and approximately 22 dolphins have died at Marineland. A solitary orca that outlived her children and the other orcas she once shared her enclosure with lives in Marineland. The practice of keeping an orca alone in captivity is illegal in the US, due to the social nature of the animals. Former employees of the park have painted a dark picture of neglect in media interviews. Dirty water, not changed often enough led to disease, eye infections even possibly blindness in some animals.

Some animal rights advocates started a petition to push Canada’s government to go further. The petition asks that existing marine parks are not grandfathered into the law. Whether the old parks exist for a while longer or not, they’ve led to their own, eventual demise. Perhaps the new law in Canada will also be an inspiration to other nations, like the US.

This morning I was sea kayaking in a cheap inflatable boat in the Gulf of Mexico. By coincidence, I saw sleek grey bodies moving through the water, dorsal fins slicing quickly. A dolphin, perhaps curious, surfaced about 6 feet from me for a second and then was gone. The dolphin had more important business than a person, as it should.

—

By Zach Fitzner, Earth.com Contributing Writer

Image Credit: Thanaphong Araveeporn / Shutterstock