China begins construction of a 'mega dam' that may cause problems for India

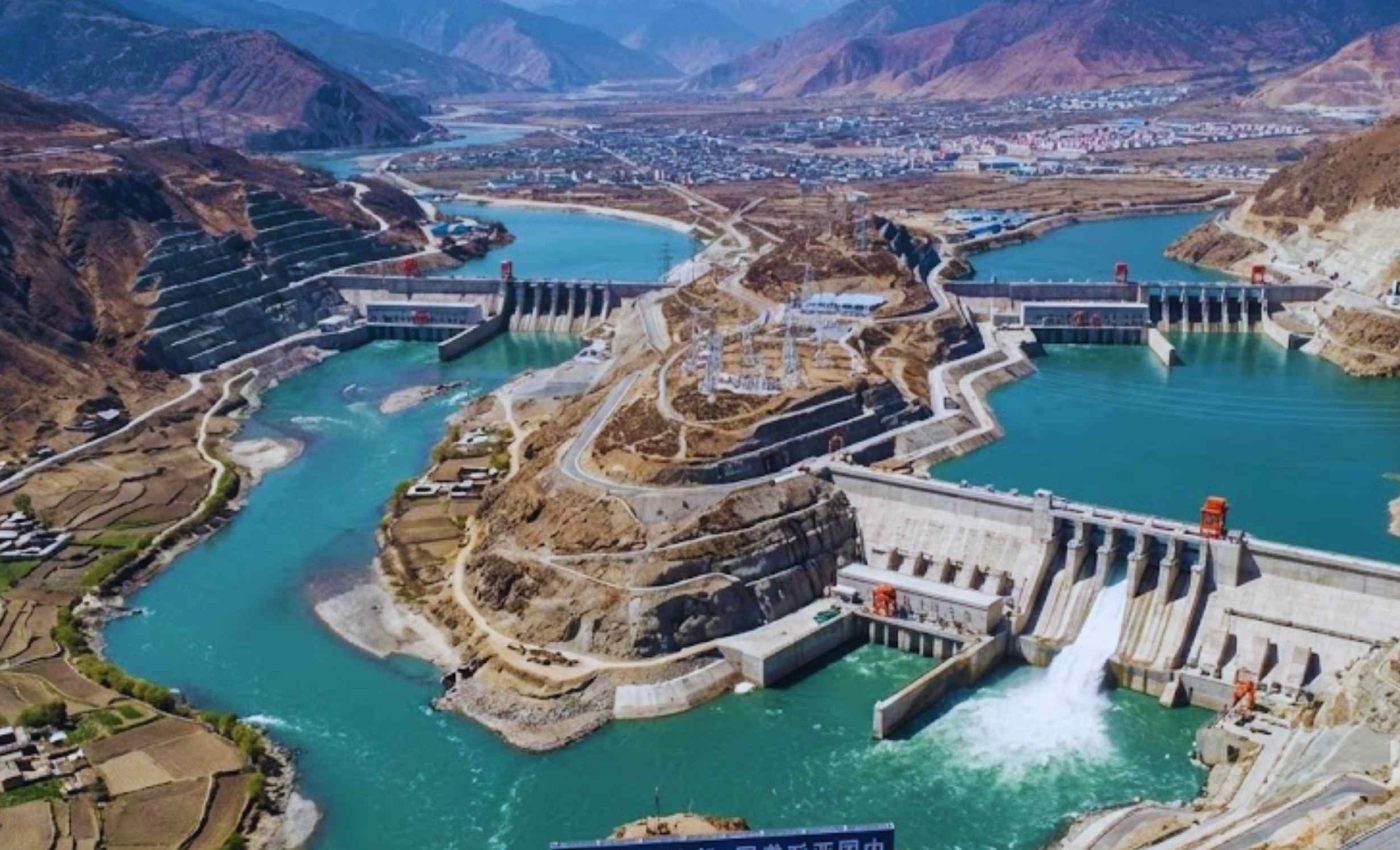

China has begun building a new hydropower “mega dam” complex on Tibet’s Yarlung Zangbo River. Designed for about 60 gigawatts of capacity, it would outmuscle every other dam system on the planet.

The project rises near the city of Nyingchi in the Tibet Autonomous Region, close to the border with India. Far downstream, communities in India and Bangladesh already wonder what happens if that tap can one day be turned down.

Yarlung dam dwarfs Three Gorges

Official plans describe a chain of five linked power stations along a canyon where the river falls about 6,600 feet in roughly 31 miles.

Recent reporting claims that it will cost about 1.2 trillion yuan and produce 300 billion kilowatt hours of electricity each year by the 2030s.

One of the scientists watching the region most closely is Taigang Zhang, a researcher at the Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research in Beijing (ITPCAS).

His work focuses on cryospheric hazards, dangerous events linked to ice and snow that can damage mountain communities and infrastructure.

Beijing has created a new state owned company, China Yajiang Group, to manage construction and later operation of the dam cascade.

Most of the electricity is meant to flow toward coastal factories and cities, with a smaller share reserved for homes and businesses in Tibet.

Premier Li Qiang has praised the development as a “project of the century” and urged engineers to put ecological safety first.

Officials also insist that the structure will not harm downstream water supplies or ecosystems, a claim that neighbors intend to scrutinize closely.

River shared with India

After leaving Tibet, the Yarlung Zangbo becomes the Brahmaputra in India, then flows into Bangladesh where it helps sustain one of the world’s largest river deltas.

Along the way it supports drinking water systems, irrigation for rice and other crops, inland fisheries, river transport, and dense clusters of riverbank towns.

A detailed graphic maps how the rivers of the Hindu Kush Himalayan region supply water to communities across South Asia.

It indicates that about 1.3 billion people live downstream, relying on river basins, land areas that drain toward a river, for freshwater.

Hydropower development in Tibet has already uprooted many communities. One recent analysis estimates that 144,468 people have been relocated and that 1.2 million could be affected by dam projects in Tibet.

Downstream governments tend to view this new dam through the lens of water security. Officials in New Delhi and Dhaka worry that sudden cuts, diversions, or accidental releases could damage farms, fisheries, and flood protection far downstream.

Fragile mountains, rising risks

The Tibetan Plateau and the Himalayas are called the Third Pole because they store amounts of ice and snow outside the Arctic and Antarctic.

That frozen water feeds Asia’s great rivers, including the system now harnessed, yet warming temperatures are shrinking glaciers and changing how meltwater arrives downstream.

In a recent open access study, researchers led by Zhang mapped thousands of high mountain lakes across the wider high mountain region.

They reported that glacial lake outburst floods have become more frequent and threaten hydropower sites and villages.

The new dam site lies in a seismically active zone, an area where earthquakes occur often enough that engineers must design for sudden shaking.

Together with unstable slopes and glacier fed lakes upstream, that location creates risks far more complicated than a simple change in river level.

People who live in mountain valleys often notice small changes in rivers or slopes long before distant agencies see them on a screen.

If resettlement pushes those residents away from riverbanks without giving them a role in monitoring, knowledge of hazards can disappear when needed most.

Clean energy and a climate puzzle

Beijing presents the Yarlung Zangbo project as a flagship renewable energy investment that will cut coal use and help meet national climate pledges.

In a country where electricity demand keeps climbing and heat waves have caused blackouts, a huge new source of steady power is politically attractive.

Yet hydropower is not carbon free over its cycle, particularly when a large reservoir, an artificial lake behind a dam, floods forests and wetlands.

A U.S. Department of Energy overview explains that reservoirs change river carbon cycles, releasing methane as vegetation decomposes and water passes through turbines.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, and over the first few decades after its release it can trap heat more effectively than carbon dioxide.

If a future Tibetan reservoir stores much rotting organic matter, its methane emissions could reduce some climate gains from replacing coal plants.

China is investing in solar farms and wind parks on the plateau, and critics argue these options could grow without social and ecological disruption.

Hydropower can steady a grid, yet relying on a single dam rather than many modest projects concentrates power over the river in few hands.

Lessons from the Yarlung Zango dam

For many observers, the Yarlung Zangbo project revives a long running question about whether upstream countries can use shared rivers to pressure their neighbors.

These projects can “threaten to turn internationally shared river-water resources into a Chinese political weapon,” said Brahma Chellaney, a professor, in one commentary.

Chinese officials reject talk of water hegemony, saying projects like the Yarlung Zangbo dam will be run to respect interests and protect plateau ecosystems.

Yet past disputes over flood season data on other shared rivers, including the Brahmaputra, make India and Bangladesh skeptical that transparency will match rhetoric.

India’s government has said it will monitor the new dam closely and take whatever steps it judges necessary to protect its interests.

Officials in Bangladesh focus on what happens downstream, concerned about both low flows in the dry months and flood pulses if operators misjudge releases.

The Yarlung Zangbo dam shows how engineering choices reach into climate policy, national security, and life along riverbanks.

How this project unfolds will shape China’s energy system and the trust of neighbors who see water as a source of power in Asia.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–