Cleopatra loses her sister again as scientists confirm they were wrong about Roman tomb remains

A skull pulled from an ancient sarcophagus in western Turkey once thrilled historians who hoped it belonged to Cleopatra VII’s politically dangerous sister, Arsinoë IV. Ninety-six years after that exhumation, new tests tell a very different story.

Gerhard Weber of the University of Vienna and his team reveal that the bones weren’t a royal woman at all but a teenage boy whose short life ended between 205 BCE and 36 BCE.

Turning a mystery on its head

Arsinoë IV died in Ephesus in 41 BCE after Cleopatra persuaded Mark Antony to have her executed. When an eight-sided mausoleum known as the Octagon emerged nearby, its Egyptian-style architecture stirred hopes that the fallen princess had been found.

That link became dogma in guidebooks, but the first red flag appeared once researchers removed the skull to Vienna for study. Early measurements hinted at a young female, yet no inscription ever proved the identification.

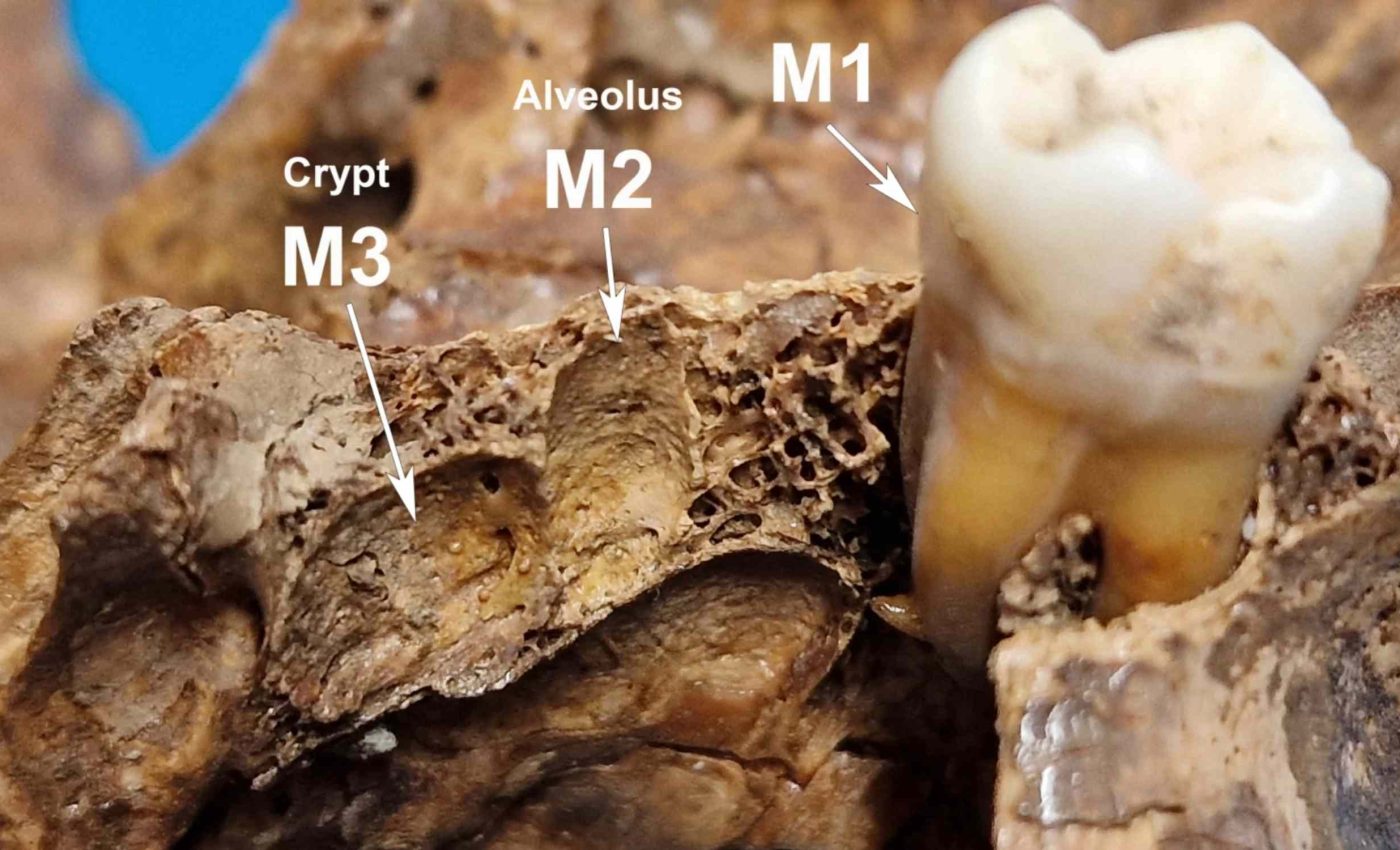

Modern micro-computed tomography archived the cranium at eighty-micron resolution, letting anthropologists probe growth plates, tooth roots, and hidden sutures.

Radiocarbon readings then tightened the time frame to the late Hellenistic era, perfectly bracketing Arsinoë’s lifetime, so anticipation soared once more.

“But then came the big surprise: in repeated tests, the skull and femur both clearly showed the presence of a Y chromosome, in other words, a male,” explained Weber. The decades-old rumor collapsed in a single genetic scan.

What the octagon really holds

DNA snippets place the boy’s ancestry somewhere between mainland Italy and Sardinia. That finding fits Ephesus’ status as a bustling Roman port where traders, soldiers, and aristocrats mixed freely.

The skeleton’s resting place sits beside the city’s Curetes Street, a marble boulevard normally reserved for civic monuments.

Burial within the walls signaled elite standing, so the child likely belonged to a powerful Roman household stationed abroad.

Architects in 1904 noted that the Octagon’s eight sides and tapered roof echoed the Pharos of Alexandria.

Even if no Egyptian princess lay inside, the stylized tribute to Egypt still puzzles historians who wonder why a Roman family adopted such symbolism.

A life cut short, not royal

Dental evidence shows the boy was only eleven to fourteen years old when he died. His first molar was pristine, yet a later-erupting premolar was cracked and worn, a mismatch pointing to serious jaw misalignment.

One cranial suture, normally open until old age, had fused far too early, warping the skull and tilting the face. Researchers suspect a developmental syndrome such as Treacher Collins or a severe vitamin-D deficit.

He also endured an unusually steep palate and under-grown upper jaw, impairing chewing and, likely, speech. Such anomalies would have been obvious in life, challenging any assumption that he was interred for heroic deeds.

Clues carved in bone and DNA

Radiocarbon calibration incorporated marine-food offsets to curb the “fish-diet” error often seen in coastal burials.

The narrow window that emerged dovetails with the late Republic period when Rome tightened its grip on Asia Minor.

Genetic mapping compared the boy’s markers to more than a thousand ancient genomes from across Europe.

Statistical overlays placed his closest matches among Etruscan-related Italians and Nuragic Sardinians, not Alexandrian Greeks.

No long runs of homozygosity appeared, so he was not the product of close inbreeding. Yet the lack of grave goods leaves open whether he was a visiting relative, a diplomat’s child, or a youthful casualty of disease.

Why the Egyptian styling still intrigues

The Octagon once stood 43 feet tall, crowned by a steep pyramid roof clad in white marble. Its echoes of Egypt’s lighthouse may simply reflect fashionable exoticism among wealthy Romans.

Another theory argues that Rome’s rulers co-opted Egyptian imagery to showcase Mediterranean dominion. If so, building a “mini-Pharos” above the harbor road offered a symbolic-boast visible to every arriving merchant.

Some scholars propose a commemorative motive, suggesting a family with Alexandrian ties chose the design to honor ancestral service in Egypt.

With the bones now ruled out as Arsinoë, researchers can pursue those architectural riddles without royal bias.

The hunt for Arsinoë resumes

Cleopatra’s defeated sister still eludes archaeologists, but the Octagon boy gives fresh direction to the search. His misidentification shows how longing for dramatic narratives can overshadow patient science.

Future digs may trace Arsinoë’s fate to a simpler grave near the Temple of Artemis where she sought sanctuary.

Until then, the Octagon’s young inhabitant stands as a cautionary tale and a human story worth telling on its own.

The study is published in Scientific Reports.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–