Earth's oceans are quickly getting darker, a big problem for all life on our planet

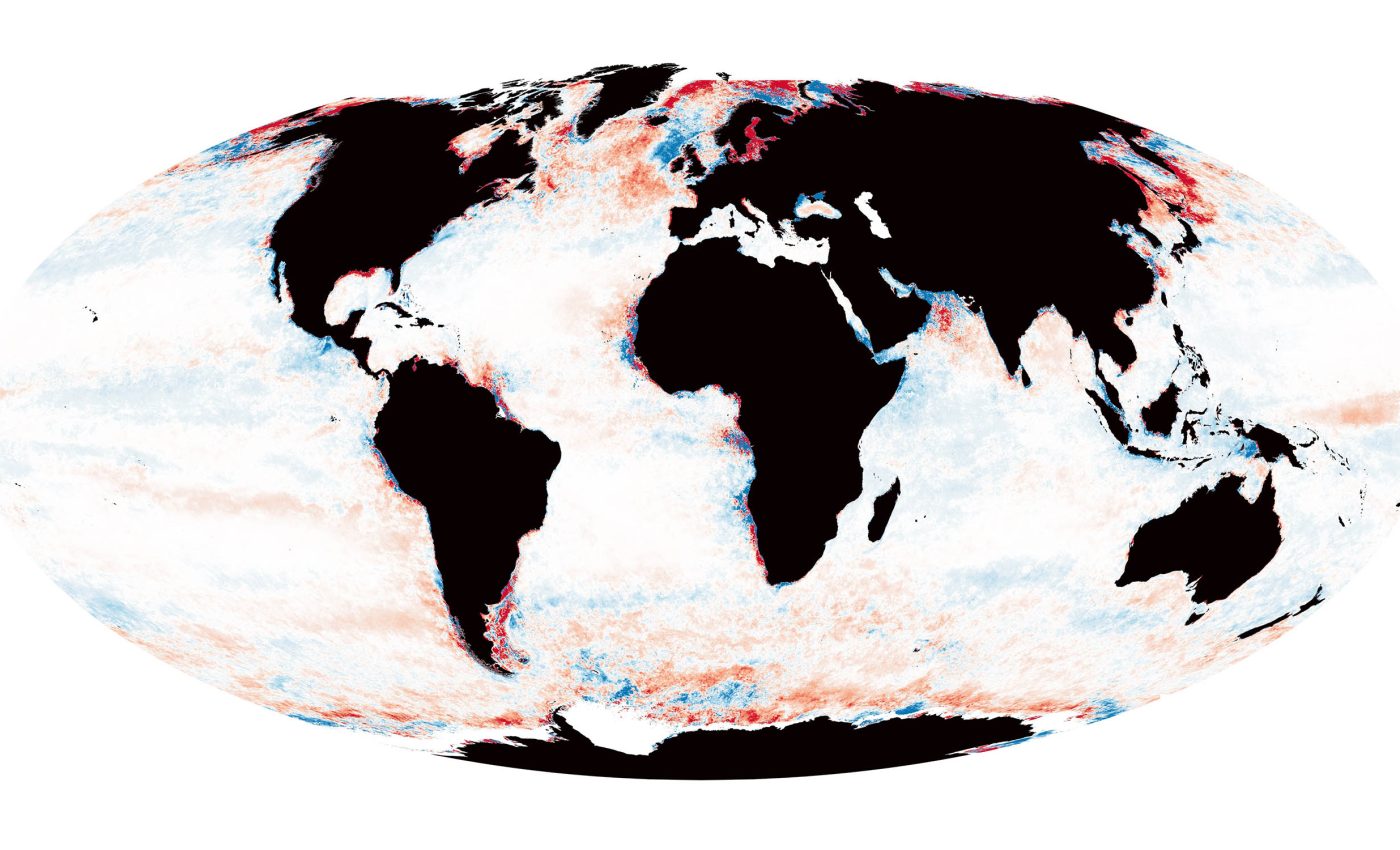

More than one-fifth of the ocean – over 46 million square miles – has gotten noticeably darker in the past two decades. This shift isn’t just about color; it signals a dramatic change in the ocean’s ability to support marine life.

Sunlight and moonlight drive life in the ocean’s photic zone – the upper layer where most marine organisms live and interact.

When the ocean darkens, less light gets through, shrinking this vital zone. That means less space for life to thrive.

Tracking ocean light loss

Scientists from the University of Plymouth and the Plymouth Marine Laboratory spent years analyzing changes in light penetration across the globe.

They combined NASA satellite data with light measurement models to track changes in the photic zone from 2003 to 2022.

The results were startling. Around 21% of the global ocean has darkened. Over nine percent of the ocean has lost more than 164 feet (50 meters) of light depth.

And in 2.6% of the ocean, the photic zone has shrunk by over 328 feet (100 meters) – an area roughly the size of India.

Interestingly, not all the news is dark. About 10% of the ocean, or 23 million square miles, has become lighter during the same time.

What’s causing the darkness?

The causes of ocean darkening vary depending on the location. In coastal areas, rain carries sediment, nutrients, and organic material from land into the ocean.

This cloudy water blocks sunlight. Agricultural runoff and changing weather patterns are partly to blame.

In the open ocean, factors like algal blooms and shifting sea surface temperatures are making it harder for sunlight to penetrate. These changes could be altering the entire structure of ocean ecosystems.

Big impacts on marine life

“There has been research showing how the surface of the ocean has changed color over the last 20 years, potentially as a result of changes in plankton communities,” said Dr. Thomas Davies, professor of marine conservation at the University of Plymouth.

“But our results provide evidence that such changes cause widespread darkening that reduces the amount of ocean available for animals that rely on the sun and the moon for their survival and reproduction.”

The ocean’s photic zones sustain essential life-supporting functions, so threats to them are deeply concerning.

“The ocean is far more dynamic than it is often given credit for. For example, we know the light levels within the water column vary massively over any 24-hour period, and animals whose behavior is directly influenced by light are far more sensitive to its processes and change,” said Professor Tim Smyth from the Plymouth Marine Laboratory.

If the photic zone shrinks, light-dependent animals will crowd the surface and compete harder for resources. “That could bring about fundamental changes in the entire marine ecosystem,” Smyth added.

Tracking changes with satellites

The team used data from NASA’s Ocean Color Web, which splits the ocean into 9km-wide pixels. For each pixel, they tracked surface changes using satellite imagery.

To estimate how deep light reached, the researchers applied an algorithm that calculates how light moves through water.

They included both solar and lunar light models to account for changes in daylight and moonlight conditions. While nighttime changes were smaller, they still had ecological effects.

Ocean darkening hotspots

Some of the largest declines in light depth were seen in the Gulf Stream and polar regions.

These areas are also among the most affected by climate change, experiencing rising temperatures, melting ice, and shifting currents – all of which contribute to changes in how light penetrates the ocean.

Coastal areas and enclosed seas, like the Baltic Sea, have also seen major darkening. Rainfall flushes in nutrients and sediment from land, triggering plankton growth.

The result is murkier water that blocks sunlight from reaching deeper layers. In shallow areas, this can disrupt fish behavior, coral health, and breeding cycles – further unsettling fragile marine ecosystems.

The full study was published in the journal Global Change Biology.

Image Credit: University of Plymouth

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–