Star in deep space has been transmitting a signal every 22 minutes for 33 years

Somewhere in the Milky Way, a tiny star named GPM J1839-10 has been sending out a radio pulse every 22 minutes. Astronomers now realize that this pattern has been repeating, almost without fail, for several decades.

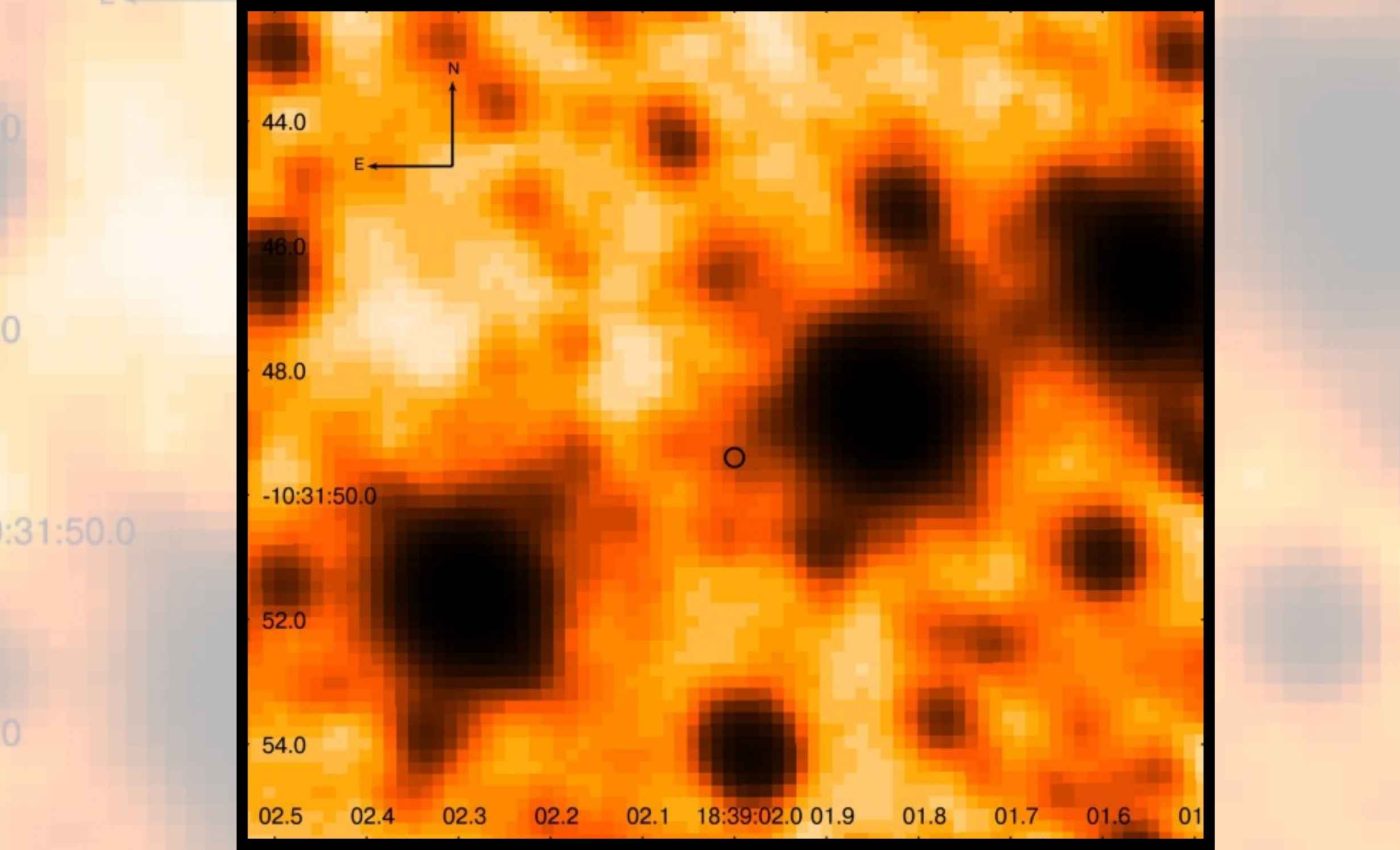

GPM J1839-10 is about 15,000 light-years away in the constellation Scutum. Its slow but steady flashing breaks the usual rules for how dead stars should behave, leaving scientists puzzled about the engine powering it.

Odd signal from GPM J1839-10

This long-term puzzle has become a focus for Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker, a radio astronomer at Curtin University in Western Australia.

Her research focuses on using large radio telescopes, instruments that catch faint radio waves from space, to map the sky and uncover rare objects.

Using the Murchison Widefield Array in Western Australia, the team scanned the Milky Way every few nights, searching for objects that blink.

The Murchison Widefield Array is a low-frequency radio telescope made of many small antennas, and its design lets astronomers monitor large areas of the sky at the same time.

Archival data from the Very Large Array in New Mexico revealed matching pulses in observations taken almost every year back to 1988.

This array, a group of radio dishes working together, showed the signal had stayed active for at least 33 years.

Together, the records showed bright bursts that lasted about five minutes, followed by roughly seventeen minutes of silence before the next pulse arrived.

Instead of slowing down the way normal pulsars do as they age, this object seems to keep rotating steadily while still emitting radio waves.

How pulsars usually behave

Most pulsars, rapidly spinning neutron stars that beam radio waves from their magnetic poles, flash every few seconds or even faster.

Their beams sweep across Earth as they rotate, so observers see a regular series of short, bright radio blips.

When pulsars are very young, they spin quickly and have plenty of energy to power strong radio emission.

As they lose energy, their rotation slows and their radio beams fade until they cross the death line, a threshold where emission should stop.

Magnetars, neutron stars with magnetic fields a thousand times stronger than typical pulsars, pour this energy into intense X-rays and gamma rays.

Reviews of these objects suggest there are only a few dozen known in our galaxy, and most spin once every few seconds.

In contrast, the star behind GPM J1839-10 rotates so slowly that theory says it should sit below the death line, unable to power radio waves.

That mismatch between models and observation is what makes this source feel less like a solved puzzle and more like an open question.

Aliens are not involved

When Jocelyn Bell Burnell spotted a radio signal in 1967, her team jokingly called it LGM 1, short for Little Green Men 1.

Soon after, more pulsars were found in different parts of the sky, and the idea that they were messages from aliens quickly faded.

For the new source, astronomers have run through the same basic checklist, looking for any hints of artificial communication.

Its pulses carry no extra patterns or data, just broad band noise across many frequencies, exactly what natural radio sources tend to produce.

On top of that, the power needed to broadcast such a strong, broad band signal deliberately would rival the output of a compact star.

Lessons from GPM J1839-10

Right now, the star behind GPM J1839-10 is still active, which means observatories around the world can keep timing its flashes.

Careful timing over the coming years will test whether the rotation stays perfectly steady or shows subtle changes that hint at the driving physics.

If the signal ever fades or switches behavior, that transition will be just as important as the steady years already recorded.

Any sudden glitch in timing or brightness could reveal whether the object is rearranging its magnetic field, shedding matter, or interacting with a companion.

Future instruments such as the Square Kilometre Array will listen more deeply to the sky and may uncover additional slow transients that help fill in this picture.

By comparing those signals with GPM J1839-10, researchers can test whether it is unusual or the first member of a larger population of long-period emitters.

For now, the safest conclusion is that nature can keep a slowly rotating compact object emitting radio waves beyond what standard theory predicts.

That gap between expectation and reality is exactly where new physics often begins.

The study is published in Nature.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–