Main chemical used for insect repellant is building up in the drinking water supply

Many people reach for insect repellents like DEET during summer evenings or outdoor trips.

A simple spray offers comfort and confidence, especially in regions where mosquito-borne infections remain active. Yet a slow chemical journey unfolds once these sprays wash into sinks, rivers, and soil.

Scientists now warn that one familiar repellent is moving across aquatic systems in rising amounts. A new wave of research urges earlier action before small traces grow into persistent environmental burdens.

DEET’s silent water footprint

DEET stands as a vital tool for protection against mosquito-borne infections. It also now appears in rivers, lakes, coastal zones, groundwater, and even treated drinking water.

“DEET has been a public-health success story for decades, but our analysis shows it is also becoming a quiet, global water contaminant,” said Yan Zhao of Dalian Maritime University.

“We shouldn’t wait for a crisis; it is time to treat DEET as an emerging pollutant that requires better monitoring and smarter management.”

Cui explained that repellents remain essential for regions facing dengue or malaria. The concern lies in uncontrolled environmental release, not consumer use.

Rising global demand adds to the challenge, as more households, farms, and industries incorporate DEET for varied purposes.

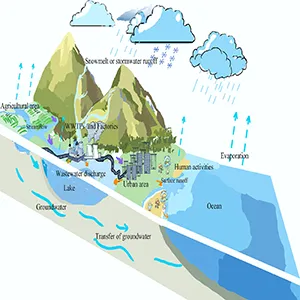

How DEET enters water

DEET originates in military research, yet now supports farming, medicine and materials science. Many products wash into drains after swimming or bathing.

Laundry removes residues from fabrics. Skin absorption leads to later release through urine. Each activity sends small chemical pulses into wastewater systems.

Wastewater plants remove only part of these inputs, allowing a sizable fraction to reach rivers. Stormwater runoff adds more from farms and land surfaces.

Rainfall also mobilizes residues from solid-waste sites, creating highly concentrated leachate that can seep into nearby groundwater.

Due to its low to moderate attachment to sediments, DEET remains mobile in water columns. These properties enable movement across long distances.

Rising contamination zones

Surveyed regions across Asia, Europe, North America, and South America report steady detection in surface waters, often at nanogram to microgram levels.

Tourist coasts show higher peaks due to direct washoff from recreational swimmers. Urban zones exhibit similar trends as treated effluent enters nearby waterways.

Groundwater samples in dense cities show notable concentrations, shaped by leaky sewage, poor sanitation, and intensive repellent use. Solid-waste sites form the most contaminated water sources, with levels reaching microgram- to milligram-range concentrations.

Sediments from lakes and marine zones also reveal consistent DEET presence, indicating long-term environmental entry.

Environmental toll of DEET

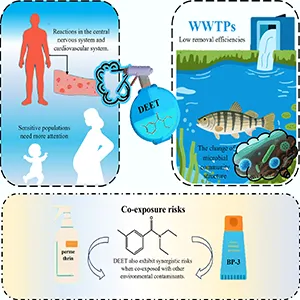

Sensitive aquatic algae show reduced cytochrome content and irreversible cell injury under high exposure. Fish and invertebrates exhibit growth limits and disrupted neural activity.

Microbial groups responsible for nitrogen cycling also shift under exposure. Altered community structure can influence ecosystem processes tied to nutrient flow.

Some evidence now points to uptake in mussels, bees, and honey, which suggests food-web movement. Researchers note that mixtures of DEET with other chemicals can intensify cellular injury.

Combined exposure with caffeine or sunscreen ingredients has produced genotoxic impacts, while joint exposure with certain pesticides increases epithelial damage. These interactions widen the scope of ecological concern.

Understanding exposure risks

Scientists use a risk-quotient method comparing environmental levels with safe-effect thresholds. A broader weighted system helps capture global patterns without overemphasizing extreme data.

Calculated global averages fall within a moderate-risk category. The highest concern centers on landfill leachate, followed by groundwater and surface waters.

Key uncertainties remain. Many regions with heavy repellent use lack long-term monitoring. Sensitive groups, like children, pregnant individuals, and immunologically vulnerable populations, may face higher risks from low-dose exposure.

Microbial adaptation, long-term exposure patterns, and possible links to antibiotic resistance remain understudied.

Treating DEET pollution in water

Advanced oxidation systems show strong potential. Reactive radicals degrade DEET more effectively than standard treatment.

Certain ozonation setups boost breakdown efficiency. Hybrid systems that combine UV, chemical agents, and filtration steps also show promise.

Microbial processes contribute in natural and engineered settings. Some bacteria harness DEET as a carbon source, breaking it into simpler compounds.

Fungal systems with enzyme-rich substrates can perform similar tasks. Yet incomplete breakdown sometimes forms new by-products, making full mineralization an important target for future work.

Researchers call for deeper study of enzyme pathways, improved purification strategies, and technologies that balance efficiency with safety.

Protecting water’s future

“Mosquito repellents are here to stay, but the way society manages their life cycles can and should change,” said corresponding author Jingwei Wang.

A coordinated global monitoring network could help map high-risk areas. Local species data would refine ecological thresholds. More research on long-term exposure effects could guide safer product design.

A well-planned system can protect both public health and freshwater environments. The science now points toward steady vigilance, smarter treatment options, and regulations that adjust as new data emerges.

The study is published in the journal Agricultural Ecology and Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–