Direct link found between solar storms and heart attacks in alarming new study

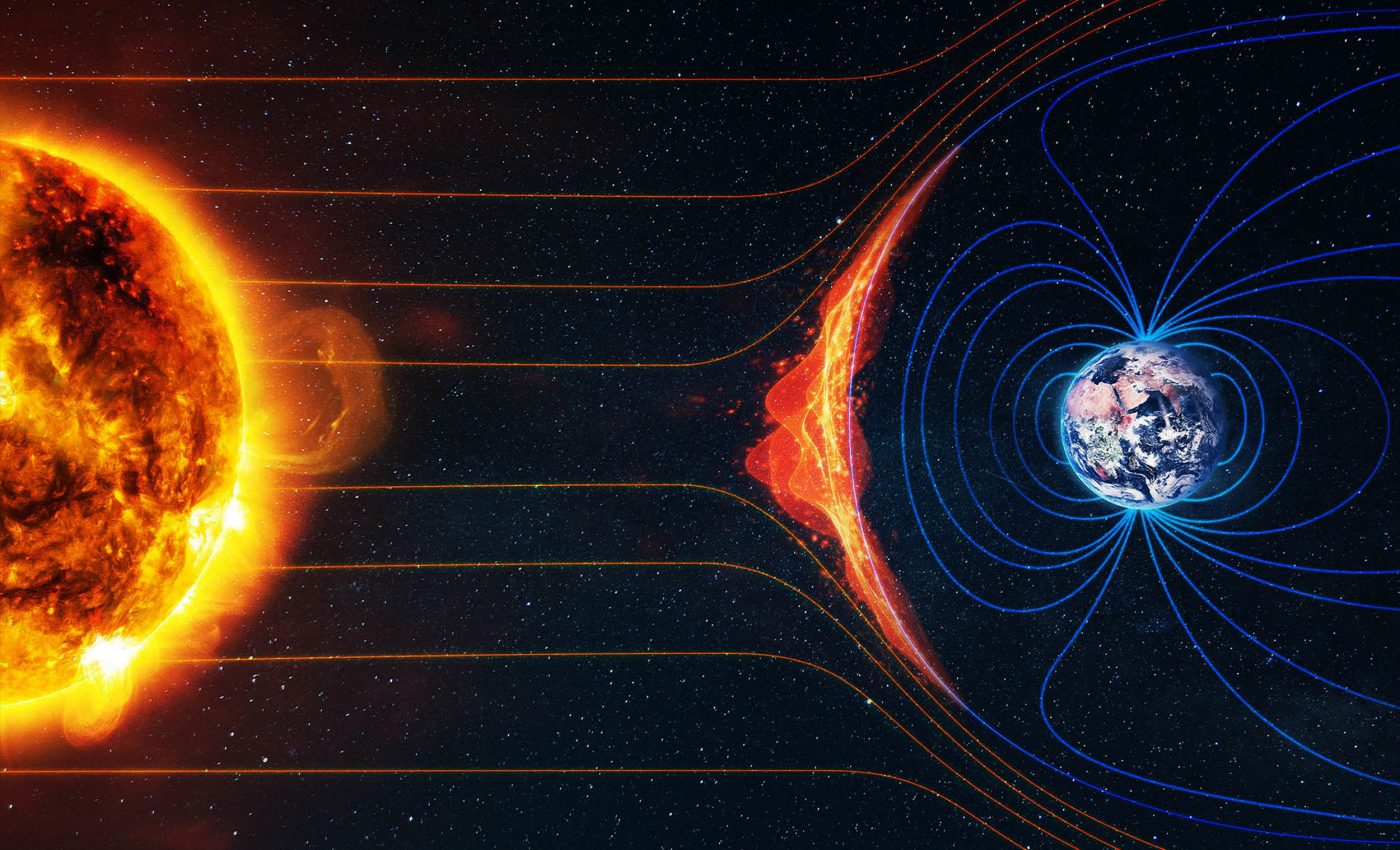

We live on a planet wrapped in a magnetic shield that waxes and wanes with solar activity. Most days, that quiet background barely draws notice. Some days, it fluctuates more strongly.

The study behind this article asked a simple question: when Earth’s magnetic field gets unsettled, as it does during solar storms, is there a direct correlation to the number of heart attacks reported in humans on Earth?

Doctors in Brazil analyzed hospital admissions for myocardial infarction (heart attacks) over several years.

They tracked age, sex, and whether patients survived to discharge. Then they set those numbers alongside daily magnetic activity scores to see whether patterns aligned.

Only after the team matched health records with space weather data did a pattern emerge clearly enough to discuss.

The corresponding author, Luiz Felipe Campos de Rezende at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE), later explained what they saw and how they checked it.

This included comparisons across age groups and a second, computer-based analysis to verify the signal.

Solar storms and human heart attacks

The question was specific: do heart attack admissions, and in-hospital deaths tied to those events, show different timing on days when the magnetic field is more disturbed?

The team also wanted to know if women and men responded the same way.

They did not try to prove cause and effect. They looked for an association in the timing of outcomes across calm, moderate, and disturbed days. That frame kept the analysis grounded in what the records could support.

The researchers used the Planetary Index (Kp-Index) – a standard global index that classifies each day’s magnetic activity from very quiet to very disturbed. That gave them a simple daily label to compare with the hospital totals.

They grouped the calendar into quiet, moderate, and disturbed days, then counted admissions and in-hospital deaths in each bucket. They split those counts by sex and age group to see where differences stood out.

What the numbers showed

On days when the Sun was highly active and solar storms disturbed Earth’s magnetic field, women had a higher rate of heart attack admissions than on quiet days. The signal was most visible among middle-aged and older women.

In the same age groups, in-hospital deaths also rose on disturbed days compared with quiet ones.

Men did not show the same clear increase on disturbed days in those groups, even though they accounted for more admissions overall in the dataset.

The study’s point was not about who has more heart attacks in general, but whether the timing shifted with space weather conditions.

Timing heart attacks with solar activity

The scientists classified the days analyzed as calm, moderate, or disturbed. The health data were divided by sex and age group [up to 30 years old; between 31 and 60; over 60 years old].

“It’s worth noting that the number of heart attacks among men is almost twice as high – regardless of geomagnetic conditions,” Luiz Felipe Campos de Rezende, a researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and the corresponding author of the article, told Agência FAPESP.

“But when we look at the relative frequency rate of cases, we find that for women, it’s significantly higher during disturbed geomagnetic conditions compared to calm conditions.

“In the 31-60 age group, it’s up to three times higher. Therefore, our results suggest that women are more susceptible to geomagnetic conditions,” Rezende expounded.

Adding layers of confidence

Statistics can mislead if one method biases the result.

To guard against that, the team used clustering, which groups similar cases without pre-labeling what should matter. They fed the model each day’s magnetic category and strength (Kp-Index), along with sex and age.

One cluster highlighted disturbed-day cases with a predominance of women in their mid-60s.

That lined up with the simpler counts, adding another layer of confidence that the observed pattern was not a quirk of a single approach.

Statistically significant link

This was an observational study using historical records from one city. Observational means no experiment and no intervention – only careful matching of timelines.

By design, that cannot prove that a magnetic disturbance triggers a heart attack.

What it can say is that admissions and in-hospital deaths among women, especially in older groups, tended to be more frequent on days when solar storms disturbed Earth’s geomagnetic field than on quiet ones within the studied setting.

The authors are clear about that limit and avoid causal claims.

Why this link is plausible

The heart runs on tiny electrical signals that coordinate each beat. Nerves rely on electrical pulses, and many body rhythms follow cycles that can be nudged by outside cues.

Some scientists think external electromagnetic variations could add a small nudge to systems already under strain.

If someone has vulnerable arteries or a rhythm on edge, even a subtle push might affect when an event occurs.

That is a hypothesis. The study did not test a mechanism, but it points to a focused question that further research can take on.

Larger datasets and forecasting

Larger datasets drawn from multiple regions and latitudes could test whether the same timing pattern holds across different magnetic environments.

More detailed patient information – medications, underlying conditions, and daily factors – could clarify who is most sensitive and why.

Pairing health records with local magnetic measurements and other environmental variables, like temperature and air quality, would help separate overlapping influences.

That kind of design moves the field from suggestive timing links toward causal explanations.

“Scientists around the world have been trying to predict the occurrence of geomagnetic disturbances, but the accuracy, for now, isn’t good,” Rezende says.

“When this type of service is more advanced – and if the impact of magnetic disturbances on the heart is confirmed – we’ll be able to consider prevention strategies from a public health perspective, especially for individuals who already suffer from heart problems,” he concluded.

Solar storms, heart attacks, and next steps

Public health teams already use short-term alerts for heat and pollution.

If future work confirms a definitively reliable association between solar storms and higher rates of heart attack admissions, hospitals could plan for a small uptick in cardiology load during strong disturbances of Earth’s magnetic field.

People with known heart disease could follow common-sense steps that clinicians routinely advise, with extra attention during solar storm notices: take prescribed medications, watch for symptoms, and avoid unusual exertion.

Those actions fit standard care and require no alarm.

Many more questions need to be answered, but the evidence presented from this study leaves no doubt that there is “something” there that justifies further investigation.

Until then, keep an eye on the Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC) alerts and act accordingly. It’s better to be safe than sorry, especially when the “being safe” part doesn’t require much effort.

The full study was published in the journal Nature Communications Medicine.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–