Dolphins around the world are showing signs of Alzheimer's-like brain disease

When a dolphin washes ashore, people rush in with towels, water, and hope. The harder question is why these smart animals end up stranded on sandy beaches in the first place.

A new study looked for answers in the brains of stranded dolphins from Florida’s Indian River Lagoon, checking for toxins and Alzheimer’s-like signatures.

The research was led by David A. Davis at University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Understanding dolphin strandings

Dolphin strandings happen when dolphins end up on beaches or in very shallow water and can’t get back to sea on their own.

Several forces can push a healthy animal into trouble, including potential issues with their brains.

Once on land, dolphins crash physiologically. Their body weight, normally supported by water, compresses organs; thick blubber overheats; and skin dries quickly, leading to shock.

In mass strandings – common in tight-knit species like pilot whales – their strong social bonds keep the group together even when one animal makes a bad turn, so many end up grounded.

Questions on dolphins’ brain

Blooms of algae known as harmful algal blooms occur more often as waters warm and nutrients build up, according to a national report.

These blooms can be fueled by cyanobacteria, which are photosynthetic microbes that sometimes make potent poisons.

The team asked whether dolphins that strand during bloom-season show higher levels of a neurotoxin called 2,4-diaminobutyric acid, and whether their brains carry molecular signs linked to Alzheimer’s disease.

They also examined whether season and toxin exposure move certain risk genes in the same direction as human disease.

Dolphins show Alzheimer’s signs

The scientists examined 20 common bottlenose dolphins that stranded between 2010 and 2019 in the lagoon.

During bloom months, the neurotoxin 2,4-diaminobutyric acid measured in the cerebral cortex was 2,900 times higher than in non-bloom seasons.

The same dolphins showed 536 genes turned up or down in patterns that map to Alzheimer’s biology.

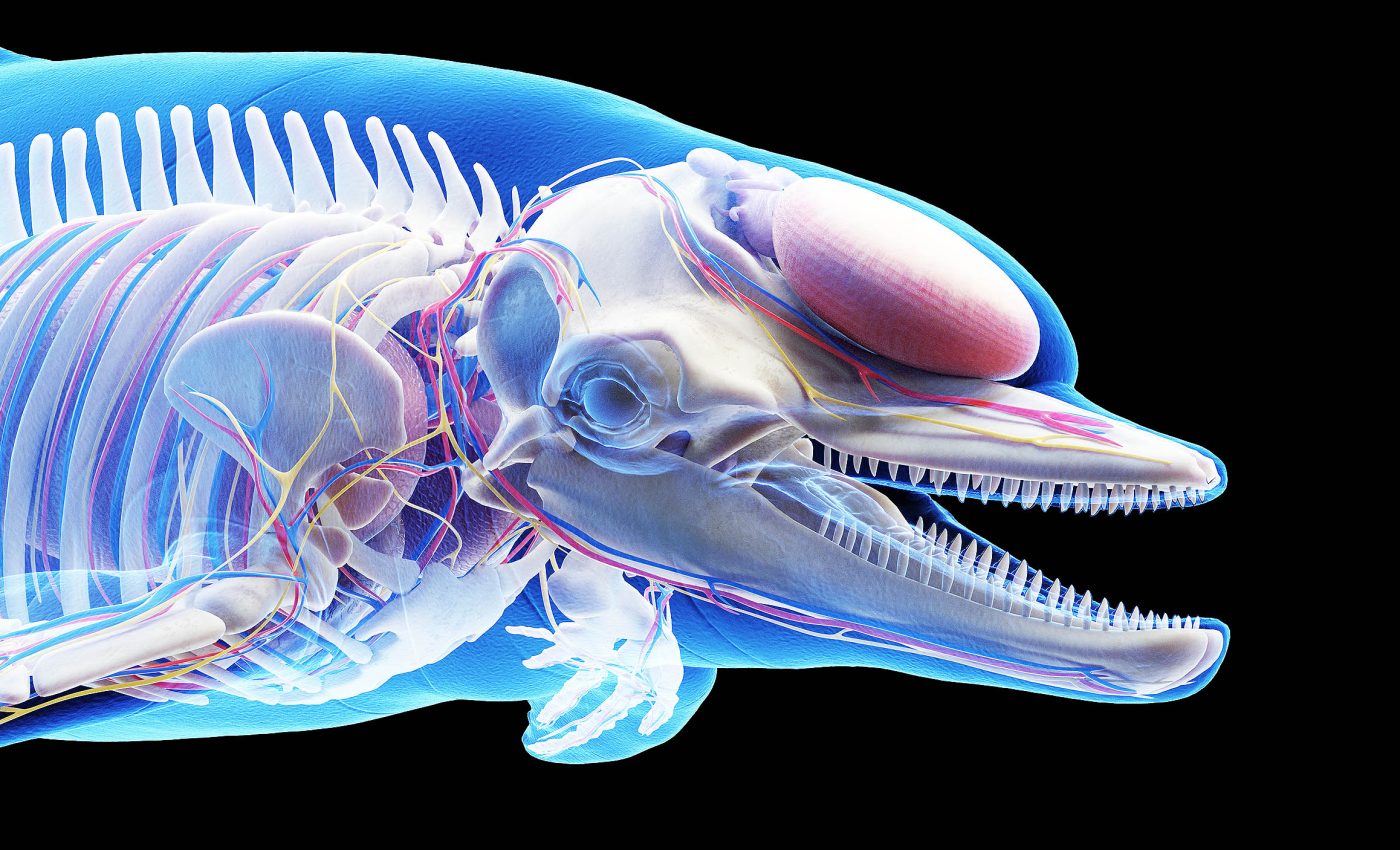

Their brain tissue also displayed amyloid plaques, which are clumps of amyloid beta protein, and abnormal tau, which is a protein that forms tangles inside neurons.

TDP-43, a protein tied to aggressive courses of Alzheimer’s, is associated with worse cognition in patients, as shown in a major review.

The stranded dolphins had TDP-43 inclusions, a marker that often tracks with faster decline.

Dolphins’ brain linked to toxins

Laboratory research shows that 2,4-diaminobutyric acid can harm nerve cells and disrupt early development in vertebrates.

In the lagoon dolphins, higher toxin levels aligned with stronger Alzheimer’s-like gene activity.

There is evidence that the related cyanobacterial toxin BMAA can trigger tangles and plaques in nonhuman primates.

That history makes the 2,4-diaminobutyric acid spike during bloom season an important red flag.

Why season stacked the deck

Season mattered for networks that control inhibitory signaling and the barrier that protects the brain.

Genes tied to GABAergic synapses shifted with bloom exposure, a sign that the chemical wiring for calming signals may be off balance.

The GABA system helps neurons put the brakes on activity, while the basement membrane supports blood vessels and limits what crosses into the brain.

Disrupt both, and you raise the odds of inflammation, leaks, and misfiring circuits.

Why dolphins’ brain matters

Public agencies call dolphins a sentinel species because they sit high on the food chain and live in the same coastal waters we use.

What shows up in their tissues can be a warning sign for coastal communities.

“Since dolphins are considered environmental sentinels for toxic exposures in marine environments, there are concerns about human health issues associated with cyanobacterial blooms,” said Dr. Davis.

This work does not prove that dementia causes strandings or that one toxin acts alone. It does show a tight seasonal link between exposure and Alzheimer’s-like signals in the brain.

“Although there are likely many paths to Alzheimer’s disease, cyanobacterial exposures increasingly appear to be a risk factor,” added Dr. Davis.

How scientists tested dolphins

Investigators measured toxins in the cerebral cortex of dolphins and checked gene activity across the whole transcriptome.

They cross-checked risk genes, looked at proteins in tissue slices, and compared bloom and non-bloom seasons.

They used stranded animals collected under federal permits and focused on high quality RNA to avoid noise in the data.

The work ran across several Florida sub-basins and spanned nearly a decade of strandings.

Protecting dolphins and their brains

The data connect warmer seasons, bigger blooms, and higher loads of a cyanobacterial toxin with Alzheimer’s-like signatures in a long lived marine mammal.

That pattern suggests exposure risk rises with hotter summers and nutrient runoff.

It also points to practical steps, including tracking bloom toxins alongside strandings and improving wastewater and farm runoff controls.

Better monitoring can help sort cause from correlation and protect wildlife and people.

Dolphin brains are not human brains, and not all molecular signals equal disease. Still, the overlap with human pathways, including TDP-43, deserves attention given its clinical weight.

Cooling the bloom engine is not simple. Warmer water and nutrient inputs pull in the same direction, which means coastal management must tackle both heat and pollution to move the needle.

The study is published in Communications Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–