Fishermen catch a large-eyed shark never before documented in the country

Fishermen in the Western Visayas brought a small, large-eyed shark to a local port, and a visiting research team recognized what they were seeing.

It was a sandbar shark, a species never before verified in the Philippines, according to a recent peer-reviewed study.

Three males were recorded at roughly 14 to 15 inches (35 to 38 centimeters) long, which is smaller than published birth size for the species, and a red flag for management.

The work was led by Roxanne Cabebe-Barnuevo of the University of the Philippines Visayas (UPV).

Why this sandbar shark turns heads

“This is the first verified report of Carcharhinus plumbeus from Philippine waters,” stated Cabebe-Barnuevo. Records like this reshape field guides, update species lists, and influence rules that affect what fishers can catch and when.

Finding very small individuals matters for another reason. Young sandbar sharks often use shallow coastal habitats as nursery areas, and consistent landings of tiny sharks can signal pressure where it hurts most.

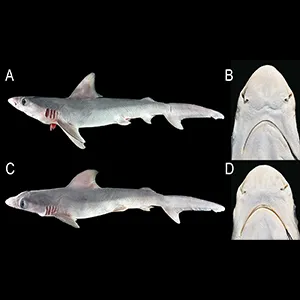

The team described the sharks with clear field traits. They noted the large eyes, the dark gray body above a white belly, and the tall first dorsal fin with all fins carrying dusky tips.

Market-based surveys give a window into what swims near the shore and what fishing gear is catching it. They also keep the spotlight on species that pass through ports without ever reaching scientific journals or museums.

Why this small sandbar shark matters

Sandbar sharks are a fixture in many fisheries across the world. “In fact, because of its numbers, moderate size, palatable meat, and high fin-to-carcass ratio, it is the primary targeted species in this area,” notes the Florida Museum species profile.

Growth and reproduction are slow in this species. That life history pattern makes populations easy to deplete and slow to rebound.

Healthy sandbar shark populations help hold food webs together in coastal waters. They feed on fish, squid, and crustaceans; mid-sized predators like these sharks can shape which species thrive.

The new Philippine records highlight a local piece of a global story. Small-scale fisheries, like those in Western Visayas, carry real weight for species that take years to mature.

What the survey actually found

The team focused on cartilaginous fish, a group that includes sharks, rays, skates, and chimaeras. Over two years of market and port visits across Panay and Guimaras, they documented 14 species, including six sharks, seven rays, and one chimaera.

Two batoids stood out as likely undescribed species. That tells us there is still hidden diversity in busy coastal waters that are fished regularly.

A ghost shark, several catsharks, spottail shark, and familiar rays also turned up. Each specimen was purchased, cataloged, and moved to a lab for analysis.

All specimens are now housed in the University of the Philippines Visayas Museum of Natural Sciences. That means other scientists can verify the identifications, compare material, and build on the work.

Confirming the shark’s identity

The team paired classical measurements with DNA barcoding, a method that compares a short stretch of DNA to reference sequences. The target marker was the mitochondrial COI gene, which is widely used for identifying fishes.

Barcode matches reinforced the field identifications and flagged the two rays that did not fit known species. When morphology and genetics agree, confidence is high, and when they disagree, researchers know where to dig deeper.

Detailed photographs and measurements were taken for every shark and ray. Those data, with the DNA sequences, create a durable record that outlives any single survey.

Voucher specimens, photographs, and barcodes make the results reusable. That is how a market observation becomes a reliable entry in a national checklist.

Why sandbar sharks are at risk

Globally, the sandbar shark is listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List. The most recent IUCN assessment reports a generation length around 20 to 26 years and links declines to overfishing and habitat loss.

Long gestation, small litters, and late maturity mean populations turn over slowly. That combination makes heavy fishing pressure especially damaging.

Local management can reduce risk in simple ways. Tracking landings, protecting known nursery areas, and tightening gear rules in shallow bays can all help.

Better data from markets are part of the fix. When small sharks appear often, agencies can respond before declines become hard to reverse.

A rare ray and a teachable moment

The survey also recorded specimens of Philippine guitarfish, including a juvenile, which adds a key piece of life history information. The species was first described from Philippine markets and is known for its restricted range.

Knowing where juveniles show up can guide protection of critical habitats. For a ray with a narrow distribution, that knowledge can make the difference.

A chimaera, sometimes called a ghost shark, turned up too. That record shows that even deep slope species can pass through coastal ports and be captured in routine monitoring.

Fishers, port staff, and scientists shared the work. When enumerators and buyers know what to watch for, small changes on the dock add up to better conservation.

The study is published in Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–