Happiness doesn't rebound in a 'U-shaped curve' as we age - here’s what really happens

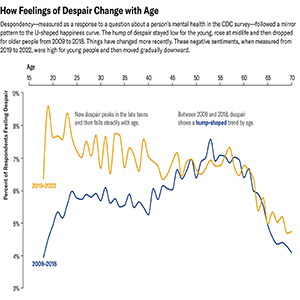

For years, a tidy story has shaped how we talk about well-being across the lifespan: people are happy in youth, hit a gloomy trough in midlife, then happiness bounces back to a cheery old age. It’s simple, it’s memorable, and it has seeped into self-help books and policy briefs alike.

A new analysis from Ludwig Maximilian University (LMU) Munich, however, suggests the real arc of happiness is messier – and the late-life rebound that anchors the U-shape may not exist at all.

The U-shape happiness age curve

The U-shape idea burst into prominence in the late 2000s, when economists published attention-grabbing cross-sectional studies showing that, on average, life satisfaction scores were higher among young and older adults than among those in their 40s and early 50s.

Those papers looked across large samples at a single point in time and sketched a neat curve by age. The result fit cultural tropes about “midlife crises,” and it stuck.

But cross-sectional snapshots have a blind spot. They blur together people of different ages and different generations.

A 70-year-old who came of age in the 1960s is not just an older version of a 30-year-old who grew up online; economic fortunes, health care, and social expectations all differ by cohort.

If you want to know how happiness changes as people age, you need to follow the same individuals over time.

Watching happiness change over time

That’s what Fabian Kratz and Josef Brüderl set out to do with Germany’s long-running Socio-Economic Panel, a nationally representative survey that has followed tens of thousands of adults for decades.

They focused on 70,922 people surveyed repeatedly between 1984 and 2017 and modeled within-person change – tracking each participant’s self-rated happiness as they moved from one life stage to the next.

The team’s approach helped to separate genuine aging processes from differences between generations.

Their curve doesn’t look like a U. On average, reported happiness declines slowly through adulthood, rises modestly in the late 50s into the early 60s (peaking around age 64), and then falls sharply.

In other words, midlife isn’t a dramatic sinkhole followed by a long, bright recovery. It’s more of a gradual slide, a brief plateau, and a late-life drop.

The illusion of late-age joy

One reason the earlier U-curve can look so clean is survivorship bias. If people who are unhappier also face higher risks of illness or premature death, then the sample of very old adults left in cross-sectional surveys will skew toward those who are doing relatively well.

That can create the illusion of a late-life resurgence even if, within individuals, happiness doesn’t rebound.

The German analysis explicitly addresses this by modeling trajectories inside people’s lives and by accounting for the fact that some participants exit the panel through death.

The researchers also argue that some past work imposed overly simplistic statistical shapes on the data – essentially forcing a U where the underlying pattern is more complex.

Real lives rarely trace perfect parabolas, and smoothing techniques can conjure pleasing pictures that travel well without being faithful to the experience beneath.

Happiness debate continues

The new paper has drawn a mix of enthusiasm and pushback. Methodologists welcome the shift from cross-sectional to longitudinal analysis and the authors’ willingness to interrogate a popular claim.

Others note that the study focuses on a single country; before we rewrite the story globally, we should replicate the method in settings with different social safety nets, family structures, and health profiles.

One of the economists behind the original U-curve findings points out that the German analysis does not adjust for life factors known to influence well-being – marital and partnership changes, income shocks, health events, and work transitions.

Those dynamics can muddy the shape of an age curve, and disentangling them will be important. Still, the core message stands: when you follow the same people over time, the dramatic late-life rebound is hard to find.

Helping happiness last in old age

The U-curve has often been used to justify extra attention to midlife. The new trajectory doesn’t deny that the 40s and 50s can be tough – caregiving squeezes, career ceilings, and financial strains are real – but it shifts the spotlight toward the years after the early-60s bump.

If happiness commonly drops off in later life, the urgent policy questions become how to prevent isolation, cushion health and income shocks, and give older adults roles that feel meaningful.

That points to practical investments. These include neighborhood designs that make it easy to see people and get around without a car. Social prescribing and community centers can create low-friction opportunities to connect.

Workplaces need protections against age discrimination. Retirement planning should include purpose, not just money.

And health systems should treat hearing loss, mobility limits, chronic pain, and depression as quality-of-life issues – not afterthoughts.

Why happiness still puzzles us

The study is careful not to claim a definitive mechanism. It doesn’t say why the small late-life rise happens or why the sharper decline follows; it simply shows that, in one large national panel, that is the average path within individuals.

We don’t yet know how much of the late-life dip reflects biology versus circumstance, or how heterogeneous these trajectories are – some people undoubtedly buck the average.

We also don’t know whether similar patterns appear in countries with stronger eldercare systems or different cultural scripts around aging.

Future work can layer in the big drivers of well-being – partnership, income, health events, caregiving, social participation – to see which combinations predict resilience.

It can also broaden the lens beyond life satisfaction to include affect (day-to-day positive and negative emotions), purpose, and meaning. Sometimes those facets move differently from the single ladder-of-life question most surveys use.

U-shaped happiness age myth

The appeal of the U-curve was always its neatness. It gave us permission to grin and bear midlife and to look forward to a sunnier sunset. The German data invite a more sober, more compassionate story.

Happiness doesn’t automatically bounce back with age; for many, it slips. That’s not cause for fatalism – it’s a prompt to design lives and communities that make the later chapters worth living.

If we accept that the curve is messier than a textbook U, we can aim our energy where it matters most and give more people a shot at a satisfying end to their story.

The study is published in the journal European Sociological Review.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–