Hidden temple discovered that could rewrite the history of an ancient empire

Archaeologists working in the Bolivian highlands have mapped a large ceremonial complex called Palaspata, about 130 miles southeast of the ancient city of Tiwanaku.

The structure sits on a ridge above long used travel routes and shows features typical of Tiwanaku sacred architecture.

This find matters because it sits outside the area where most scholars expected firm Tiwanaku influence.

It points to a wider political and religious footprint than many reconstructions allow for the first millennium in the southern Andes.

Finding the Palaspata complex

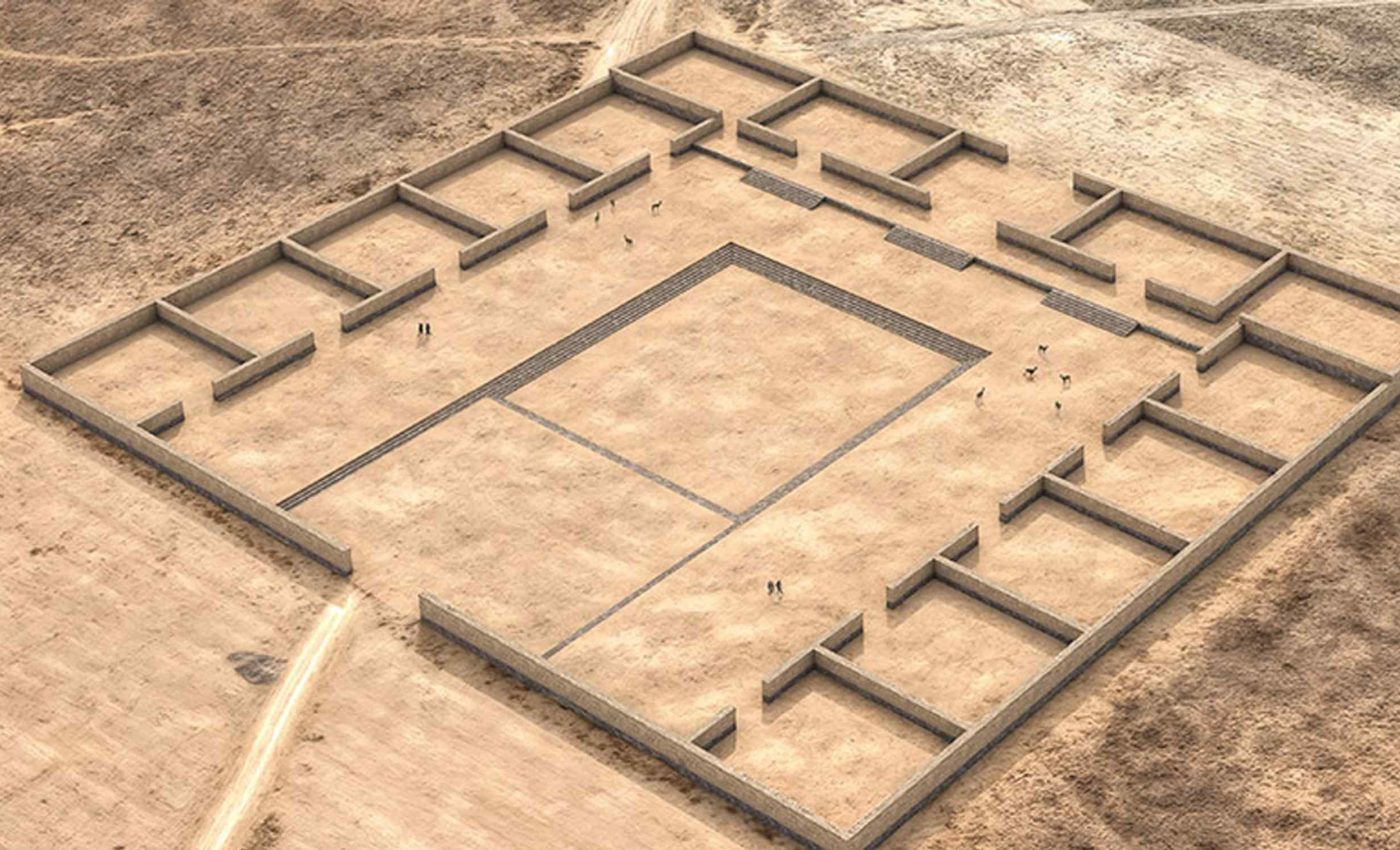

The Palaspata complex enters the record through a peer-reviewed study that describes a rectangular, modular temple built with a terraced platform and a sunken court.

It measures roughly 410 by 475 feet and encloses 15 rooms around a central plaza, with the main entry facing west.

Dr. José M. Capriles is the lead author and an associate professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University (PSU).

His team argues that Palaspata sat at a junction linking highland, plateau, and eastern valley corridors.

The orientation of the entrance lines up with the solar equinox, a typical cue in Andean ceremonial design. Surface finds include decorated pottery and drinking vessels that fit Tiwanaku styles tied to public ritual.

Archaeologists also noted keru cups scattered on the surface, which match feasting and formal gatherings. The red sandstone perimeter stones still trace the outline of the building.

“Because the features are very faint, we blended various satellite images together. Most economic and political transactions had to be mediated through divinity, because that would be a common language that would facilitate various individuals cooperating,” said Capriles, explaining how remote sensing revealed the faint plan.

Researchers combined satellite imagery with low altitude drone photography and 3D photogrammetry to produce a digital model. The model helped confirm the modular layout and the west facing entrance alignment.

Tiwanaku people and Palaspata

The ancient city of Tiwanaku developed on the south shore of Lake Titicaca and led a wide network of communities from about A.D. 500 to 1000.

Farmers and herders in these heights built monumental platforms, carved monoliths, and large plazas in stone.

Tiwanaku rose on the altiplano, a high plateau near 12,600 feet where frost and thin air challenge crops.

Llama caravans linked scattered settlements and carried goods between the lake basin, valleys to the east, and coastal deserts to the west.

Trading hubs, ritual centers, and residential mounds marked the landscape under Tiwanaku’s sway. Scholars still debate how much control the central city exercised beyond its core.

Why Palaspata matters

Palaspata lies southeast of Lake Titicaca, off the usual search grid for Tiwanaku structures of this size. Its placement by a long used corridor between La Paz and Cochabamba hints at planned oversight of movement.

The temple’s scale and labor investment suggest state level backing rather than a local shrine.

In that light, Palaspata reads as a gateway that materialized authority through ceremony, gathering, and storage tied to traffic and exchange.

The complex also links ritual and logistics in a single place, which fits how Tiwanaku often joined sacred power to political action. It expands the map of where that blend operated in practice.

What happened to Tiwanaku

A Bayesian analysis of 102 radiocarbon dates narrows the city wide collapse to around A.D. 1010 to 1050. The modeling tracks the end of monument building, formal burials, and permanent residence across a few decades.

Independent evidence from lake sediments points to a prolonged drought that peaked near 1025 C.E. and stressed highland societies.

Some researchers link that aridity to political unraveling, while others see social conflicts rising before the worst climate signals.

These different readings show why precise site dates and regional climate curves both matter. Palaspata adds a new node to test ideas about how power stretched eastward and how networks failed.

What the artifacts say

The presence of keru drinking cups, used for chicha made from maize, signals planned feasts that tied people together across distances. Maize from lower valleys would have moved uphill to fuel events in the highlands.

Feasts were not just meals. They helped seal alliances, settle accounts, and publicize decisions in a world where sacred ritual, politics, and commerce fit tightly together.

How the team built the case

The map of Palaspata draws on surface survey, drone flights, and a stitched image mosaic that pulls out subtle soil and stone contrasts. Those filters highlight the red sandstone perimeter and faint interior walls.

Nearby excavations at Ocotavi and Cayhuasi add context for the settlement cluster on the ridge and plain. Together they outline a 75 hectare landscape with ritual and domestic features.

This discovery shows how new tools can change long held assumptions without digging a single deep trench. It also shows how careful mapping can reset where we look for state investment and control.

Archaeology is not only about finding objects. It is about testing ideas with better evidence, clearer timelines, and broader comparisons.

What comes next for Palaspata

Future work aims to date construction phases at Palaspata and tie them to regional movements of people and goods. More sampling could connect the temple’s use to known episodes of stress or growth.

Charcoal and bone from linked sites will go through radiocarbon dating, a method that measures the decay of carbon 14 to estimate age ranges.

With tighter ranges, researchers can test whether ceremonies at Palaspata rose with trade and fell with conflict.

Local communities and authorities are now planning how to protect the ridge while field teams document what remains. That collaboration will help keep both the science and the heritage on solid footing.

The study is published in Antiquity.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–