High-tech tool helps scientists identify coral reef fish by sound

From the bellowing songs of whales to the clicks and pops of fish species, marine life communicates with sound in ways that science is just beginning to understand. Coral reefs, with their dazzling biodiversity, are especially noisy places.

Until now, however, scientists have lacked a reliable method to untangle these soundscapes and connect specific sounds to individual fish species. A new study has changed that.

Experts from FishEye Collaborative, Cornell University, and Aalto University have introduced an innovative tool that pairs 360° video with spatial audio recordings.

The research has opened a new dimension in understanding the secret voices of fish.

Diversity makes decoding difficult

Traditional underwater recorders capture dense layers of thumps, clicks, and pops. While useful, these sounds are difficult to trace to specific species.

Coral reefs often host hundreds of fish species, and only a few have had their calls clearly identified.

“When it comes to identifying sounds, the same biodiversity we aim to protect is also our greatest challenge,” explained Dr. Marc Dantzker, executive director of FishEye Collaborative.

“The diversity of fish sounds on a coral reef rivals that of birds in a rainforest. In the Caribbean alone, we estimate that over 700 fish species produce sounds.”

A new way to listen

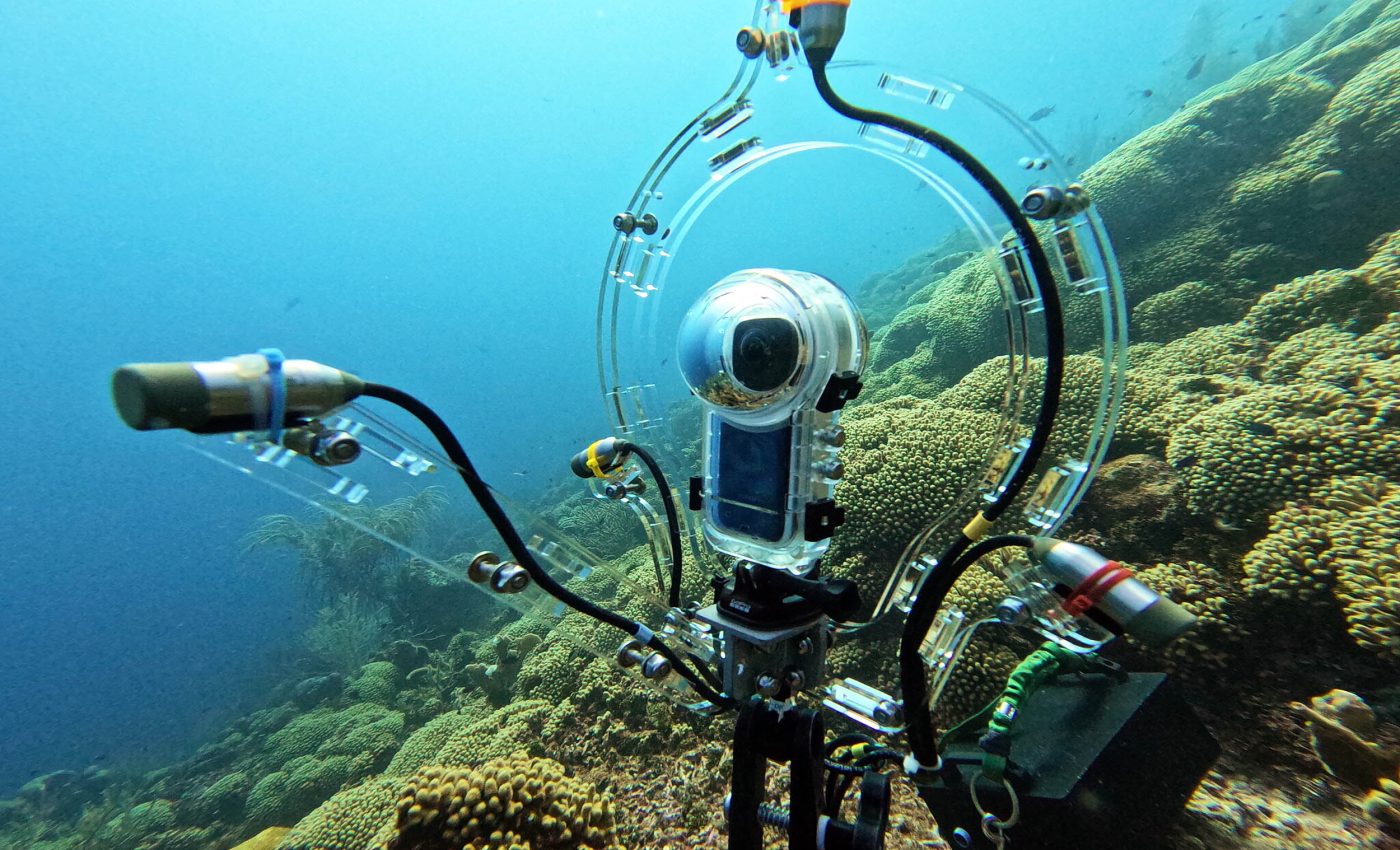

The device, named the Omnidirectional Underwater Passive Acoustic Camera (UPAC-360), combines hydrophones and a 360° camera.

This pairing allows researchers to both hear and see which fish makes each sound. On reefs in Curaçao, the team attributed sounds to 46 fish species, with more than half never before recognized as sound-producing.

This breakthrough has produced the most extensive collection of natural fish sounds ever published. The growing library is available online.

Teaching machines fish voices

The identified sounds now provide the foundation for training machine-learning models to recognize fish species automatically.

“We are a long way from being able to build ‘Merlin’ for the oceans, but the sounds are useful for scientists and conservationists right away,” said Dr. Aaron Rice, senior author of the study.

“By identifying which species make which sounds, we’re making it possible to decode reef soundscapes, transforming acoustic monitoring into a powerful tool for ocean conservation,” noted Dr. Dantzker.

Capturing fish sounds

The technology can be deployed without human presence, recording continuously across long time spans. This makes it possible to capture previously undocumented sounds.

“The fact that our recording system is put out in nature and can record for long periods of time means that we’re able to capture species’ behaviors and sounds that have never before been witnessed,” said Dr. Rice.

Reefs under growing threat

Shallow tropical reefs cover only 0.1 percent of the ocean floor but support around a quarter of all marine species. Yet they face severe declines from climate change, pollution, and overfishing.

“These reefs are declining rapidly, threatening not just biodiversity, but also the food security and livelihoods of nearly a billion people who depend on them,” said Dr. Dantzker. “In response, governments and NGOs are investing billions in reef protection and restoration.”

“That’s not enough, so we must ensure that we spend these limited funds effectively. We need to track how reefs are responding both to the stressors and the interventions.”

Until now, the loudest species – like dolphins, whales, and snapping shrimp – have overshadowed the many other voices in the sea.

By discovering the identity of these hidden voices, acoustics can become a powerful indicator of reef health and resilience, as well as a strategy for broader and deeper monitoring.

Combining fish sound and vision

To build the UPAC-360, the team adapted spatial audio technology often used in virtual reality. “Spatial audio lets you hear the direction from which sounds arrive at the camera,” explained Dr. Dantzker.

“When we visualize that sound and lay the picture on top of the 360° image, the result is a video that can reveal which sound came from which fish.”

Although this library is the most comprehensive ever created, it only scratches the surface of reef diversity. The researchers plan to expand recordings across the Caribbean and extend them to reefs in Hawai‘i and Indonesia.

With every addition, the underwater soundscape becomes clearer, offering science a new lens to monitor, protect, and perhaps one day predict the future of coral reefs.

The study is published in the journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–