DNA from famous extinct horse species found next to a wooden spear that killed it

Scientists have reconstructed the genetic blueprint of Schöningen horses – an ancient horse species (Equus mosbachensis) that became extinct.

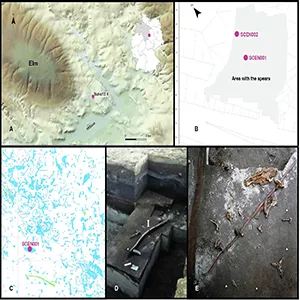

The horse bones came from Schöningen in Germany, and they reaches back roughly 300,000 years. A new study reports nearly complete mitochondrial genomes from two animals found beside those famous wooden spears.

The team shows these horses belonged to the maternal line that eventually led to today’s horses. The work also sets a new milestone for ancient DNA recovered from an open air site – this sample is older than any previous example taken outside caves or permafrost.

Why Schöningen horses matter

The work was led by Cosimo Posth, Ph.D., at the University of Tübingen. His research focuses on ancient DNA – genetic fragments preserved in old bones or sediments.

In a report, the team described how the Schöningen finds expand what is possible at open air sites. They also noted Schöningen is well known for its 300,000-year-old wooden spears, the oldest complete hunting weapons ever discovered.

The ancient horses’ maternal genomes do not sit among modern diversity, they sit beneath it. The sequences fall on deep branches, showing a previously hidden split inside mitochondrial DNA. This is the genetic material found inside the cell’s energy making structures.

Horses have a long backstory in North America and Eurasia, with movements across the Bering Land Bridge, a land connection between Siberia and Alaska that was present during ice ages.

A landmark genome from permafrost shifted the Equus family’s origin back to about 4.0 to 4.5 million years.

Reading 300,000-year-old DNA

Researchers sampled the petrous bone of the Schöningen horse – the dense skull bone that protects the inner ear – because it often shelters DNA.

They then used targeted capture and careful filtering to fish out surviving fragments and reduce errors caused by chemical damage.

The Schöningen bones lay in wet, low oxygen mud for ages, which helped protect molecules that usually fall apart in the open air. That waterlogged setting created anoxic conditions – lacking the oxygen that speeds decay in warmer places.

The team emphasized that very old DNA can be recovered even when conditions appear poor at first glance, noting that even in seemingly unfavorable environments such as open air excavation sites, extremely ancient DNA can still survive and be recovered.

Earlier open air recoveries reached about 240,000 years with straight-tusked elephants from Germany. That earlier record set expectations that Schöningen has now exceeded by a wide margin.

Horse history from genomes

Phylogenetic tests place the Schöningen sequences as deep, separate branches within the maternal line that includes living horses.

That means the extinct Equus mosbachensis shared a more recent maternal ancestor with modern horses than with other extinct horse groups.

The samples also clarify how ancient horse populations spread and mixed between continents. Two major waves moved through Beringia, and later back movements blended populations that had split earlier.

These genomes come from the maternal side only, since the sequences are from mitochondria. A maternal lineage, ancestry traced through mothers, cannot reveal past mixing from fathers, but it is powerful for timing events.

Molecular models estimate a mean genetic age for one Schöningen lineage at about 360,000 years. That timing helps bracket when the maternal line that leads to modern horses first began to branch. The approach uses a molecular clock, a method that estimates time from genetic mutation rates.

Schöningen horse DNA survival

Schöningen is an open air site, an excavation area not buffered by cave walls or permanent ice. Open sites usually see hotter summers, colder winters, and more microbes, all of which are rough on DNA.

Even so, the lakeshore mud kept oxygen low and temperatures relatively steady down in the sediments. That palaeolake – an ancient lake preserved in geology – left layers that trapped bones, tools, and plant remains together.

There is an ongoing debate about exactly how old the spear horizon is at Schöningen. A team reanalyzed the wooden tools and proposed an age near 200,000 years for that layer.

The genetic dating from the Schöningen horse supports an older timeline near 360,000 years for the sampled lineage.

That estimate lines up with biostratigraphic evidence, and it underscores how DNA can complement other dating tools when layers are complex.

Horses, hunters, and humans

Schöningen preserves a tight snapshot of people and prey, not just isolated bones. The find includes complete spears and clustered horse remains with cut marks that match systematic butchery, a hallmark pattern in zooarchaeology.

A detailed analysis of the horse kill site concluded that hunters focused on horse family groups through multiple seasons. The pattern points to organized, cooperative hunts run throughout the year.

This new genetic work ties that behavioral scene to a deeper biological history. The horses eaten at that lakeshore were part of the maternal line that would eventually give rise to the horses alive today.

The result shows why ancient DNA belongs in every archaeologist’s toolkit. When bones, tools, and genomes share the same ground, the past becomes clearer and more precise.

The study is published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–