Household dust contains microplastics that accelerate aging at the cellular level

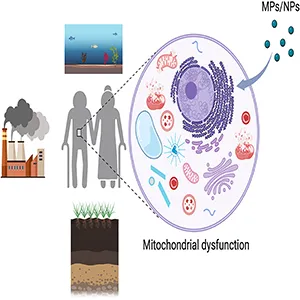

Tiny plastic particles are not just in oceans, food and bottled water. These microplastics also settle in ordinary house dust, where they can get into the body and stress the mitochondria that keep our cells running.

A recent scientific review connects those exposures to wear and tear on mitochondria, the structures in cells that manage energy and help control stress responses over a lifetime.

Microplastics and mitochondria

The new paper gathered evidence on how microplastics and nanoplastics move from air, food, and dust into the body, where they can lodge in tissues and interact with cells.

It also maps how these particles can damage mitochondrial membranes, interrupt energy production, and amplify stress signals.

“Mitochondrial dysfunction is widely recognized as a hallmark of aging,” wrote Liang Kong of the Institute of Translational Medicine, Medical College, Yangzhou University, who led the team that wrote the review.

Why mitochondria matter

Mitochondria act like cell control centers for energy and stress management. When they falter, cells have a harder time powering essential work and clearing up damage.

Small hits add up. Over time, chronic strain on mitochondria can accelerate age-related changes in tissues and raise the odds of diseases.

Dust as a daily exposure

Indoor environments collect fibers and fragments from carpets, clothing, furniture, and packaging.

Multiple indoor studies and a comprehensive review show that dust and air inside homes often contain more microplastic particles than outdoor air.

People inhale and swallow some of this dust during normal activities. Infants and toddlers tend to take in more, which means early life exposure deserves careful attention.

Microplastics in drinking water

Drinking water is another route. One high-resolution study counted about 240,000 plastic particles in each liter of bottled water, and about 90 percent were at the nano scale.

Microplastics have also been identified in water bottled in glass.

Smaller particles can move more easily through the body. That raises reasonable questions about where they travel to and what they do once they arrive.

Plastic in human tissues

Scientists have detected plastic polymers circulating in human blood. A biomonitoring study measured a mean concentration of about 1.6 micrograms per milliliter across 22 healthy donors.

That finding does not tell us the health impact by itself. It does show these particles are bioavailable and able to reach internal compartments that matter.

What about the brain

Animal experiments indicate that some nanoplastics can pass the blood-brain barrier and switch on inflammatory cells in the brain.

Lab work with brain endothelial cells also shows tight junction changes and leaky barriers after exposure.

These observations do not prove what happens in people. They do point to a plausible path for neurological effects that warrants careful human research.

Why this links to aging

The review highlights mitochondrial injury as a central mechanism. When mitochondria lose structure or fail to maintain quality control, cells slide toward chronic inflammation and impaired repair.

Those processes are tied to age-related decline in muscles, vessels, and nerves. If microplastics and nanoplastics push mitochondria in that direction, day to day exposures could shape long-term risk.

Clues from human outcomes

Researchers recently examined carotid artery plaques removed during surgery and tracked future events.

In that clinical study patients whose plaques contained polyethylene or polyvinyl chloride had a 4.53 times higher risk of heart attack, stroke, or death over about 34 months.

The particles were visible under electron microscopy in plaque macrophages. That kind of signal aligns with the idea that persistent plastic fragments can stoke inflammation in places where it matters.

What can you do now

You cannot avoid plastics entirely, but you can lower contact in practical ways. Regular vacuuming with an air filter and damp dusting reduces indoor particle loads.

Cool food before storing, and use glass or stainless steel for hot leftovers. Simple cooking and storage habits cut down on plastic wear and tear.

Mitochondria, microplastics, and human health

Better exposure tracking is coming, including methods that count smaller particles with chemical fingerprints. Controlled human studies can then relate measured body burdens to early mitochondrial stress signals.

Teams will watch for changes in energy production, oxidative damage, and inflammatory markers. If the patterns hold, public health guidance can target the highest yield sources.

House dust sits at the intersection of multiple sources, including textiles and packaging. Concentrations indoors can exceed outdoor levels because there is less mixing and more shedding from surfaces.

Cleaning practices matter. So do choices on fabrics, filters, and storage, which can lower the total you breathe and swallow without much fuss.

Evidence is converging on a simple point. Tiny plastic particles are getting into people, and mitochondria look like a key stress target.

Scientists will keep testing how size, polymer type, and additives influence risk. As the picture sharpens, small changes at home can help you stay on the safer side.

The study is published in Food and Chemical Toxicology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–