"Wildfire paradox" tries to explain why fires are raging across the entire planet

Wildfire headlines can feel all over the place. One summer brings walls of flames putting millions of people in danger. The next brings lots of fires, but very few near humans. This is called the “wildfire paradox.”

Here’s the twist: the planet has actually seen less land burned in recent years, yet more people are ending up in the path of flames.

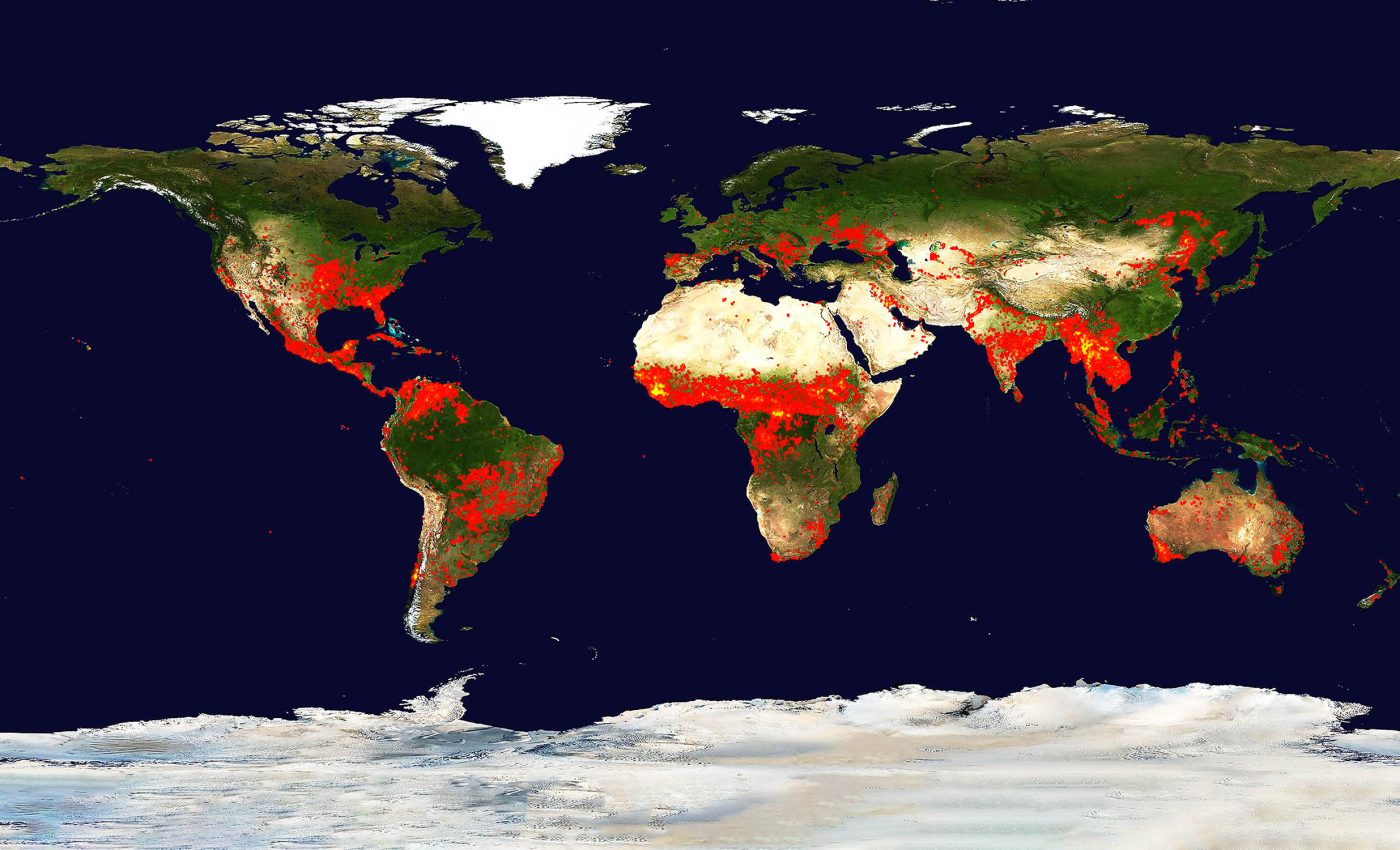

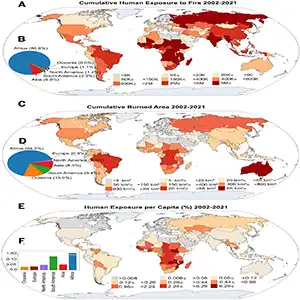

From 2002 to 2021, the total area that burned worldwide went down by about a quarter.

Over the same years, the number of people directly exposed to wildfires – meaning flames reached the places where they live – went up by roughly 40%. Those two facts sit side by side. They also change how we think about risk.

The “wildfire paradox” term fits. The land is burning less, but exposure is rising because more homes and towns now sit where fires naturally occur. That shift is not random. It grows out of how and where people build.

Africa carries the weight

Across that same period from 2002 to 2021, the authors estimate that about 440 million people experienced a wildfire reaching their community.

Year to year, exposure climbed by several hundred thousand people annually on average, even as total burned acreage fell. Fewer acres does not automatically mean fewer people in danger.

Most news stories highlight wildfires in California, Greece, or Australia. Yet wildfires in these places account for less than 2.5 percent of all exposures. Africa, often missing from headlines, saw 85 percent of them.

Just five countries – Congo, South Sudan, Mozambique, Zambia, and Angola – accounted for about half of the global total.

The United States, Europe, and Australia combined made up less than 2.5%. That contrast says more about population patterns and fire frequency than media attention.

“We are surprised by the disproportionate impacts of wildfires on humans in Africa,” said Dr. Mojtaba Sadegh, Climate and Wildfire Analytics Lead at UNU-INWEH.

“We knew that around 65 percent of global burned area occurs there, but their 85 percent share of human exposure shows a pronounced impact that deserves more attention.”

Farming plays a big role. Fields break up grasslands and stop large fires from spreading. But they also bring villages and farms closer to the flames.

Wildfire paradox and climate change

Climate change is amplifying fire danger. Since 1979, extreme fire weather jumped by more than 54 percent. Fire seasons now stretch longer. Nights, once safer, often stay hot and dry enough for fires to keep burning.

Still, the story changes depending on where you look. Africa shows smaller fires but far more people exposed.

In North and South America, invasive plants help fires grow larger. Europe tries to suppress fires, yet expanding settlements keep raising the risks.

Human actions reshape fire risks

Study co-author Professor Amir AghaKouchak noted that while the human exposure to fires is rising, the team saw that burned land is shrinking by 26 percent.

“In Africa, farming has broken up large grasslands into smaller fields, which stops fires from spreading as widely but also puts more villages and farms closer to fire-prone land.”

“In the Americas, invasive plants have fueled bigger and more frequent wildfires, showing how human actions can change fire risks in very different ways.”

The numbers back this up. Nearly half of the world’s people now live in the wildland–urban interface, an area covering less than 5 percent of Earth’s surface.

The study shows that population growth and migration explain about a quarter of all exposures. Without these changes, exposure levels would have fallen alongside shrinking burned area.

Instead, exposure density nearly doubled. In plain terms, more people are living inside or right next to land that burns.

Beyond burned land

Focusing only on how much land burns hides the real danger. Intense fires make up just 0.01 percent of all events, but they exposed 2.7 million people and burned 5 percent of the total land in the study.

Regions like Western North America, Southern Europe, and Southern Australia faced far more human loss than their share of exposures suggested.

“Wildfires are no longer seasonal or regional anomalies; they have become a global crisis, intensified by rising heatwaves, worsening droughts, and drastic land use changes,” said Professor Kaveh Madani, Director of UNU-INWEH.

“But instead of stepping up to confront this threat, some of the world’s biggest economies are rolling back protections, leaving vulnerable regions and communities to shoulder the heaviest burden.”

The wildfire paradox needs solutions

The study warns that measuring only burned land misses the true danger of wildfires. What matters most is how close people live to fire-prone areas. As populations expand into these zones, exposure to wildfires rises even if less land burns.

The authors stress the need for stronger fire management and strategies tailored to local conditions. Communities require infrastructure designed to withstand fire, along with better preparedness.

At the same time, global climate action is essential to slow the worsening of extreme fire weather. Without these combined efforts, more lives will remain directly in the path of devastating wildfires.

The study is published in the journal Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–