Interstellar object appears out of nowhere and stuns astronomers with its size and speed

Astronomers have recently added a new member to the small club of confirmed interstellar objects. The icy wanderer, known as 3I/Atlas, was officially recognized this week by the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center (MPC).

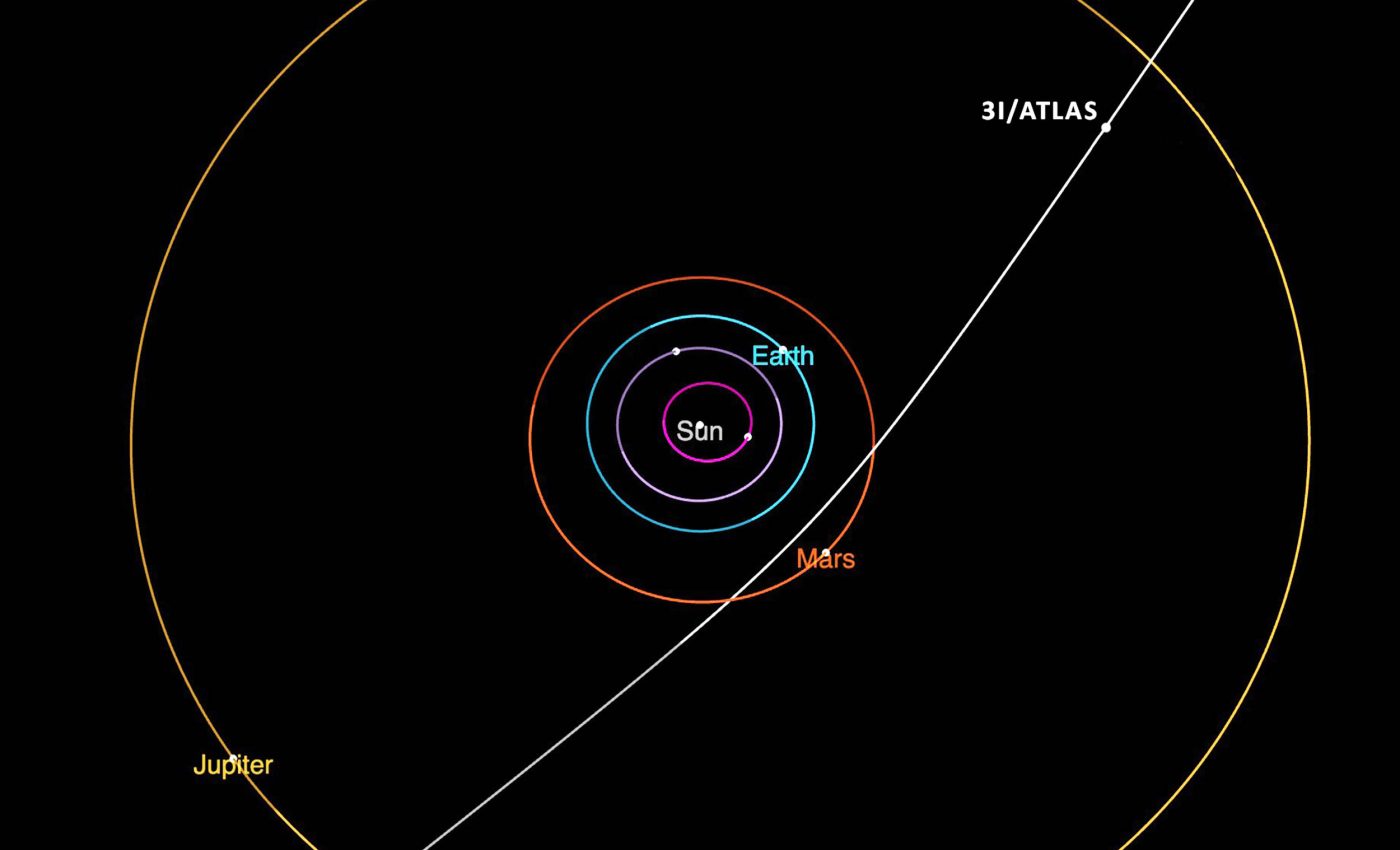

Observations showed it is racing through the solar system on a hyperbolic path – one that will carry it back into interstellar space after a brief celestial cameo.

A fuzzy comet with incredible speed

Early images of 3I/Atlas revealed the hazy glow typical of a comet. “It looks kind of fuzzy,” said Peter Veres, an astronomer at the MPC who helped confirm the object’s status. “It seems that there is some gas around it, and I think one or two telescopes reported a very short tail.”

That fuzzy halo is created as sunlight warms the comet’s surface, releasing dust and gas that trail behind it. Current estimates suggest the nucleus spans six to 12 miles (10 to 20 kilometers).

Because icy bodies reflect sunlight efficiently, the true size may prove smaller if the surface is especially bright.

What is certain is the object’s speed. Preliminary calculations put its velocity at more than 60 km per second (roughly 135,000 mph). At that speed, solar gravity cannot capture it, confirming its extrasolar origin.

Spotting an interstellar traveler

The discovery began on Tuesday when a telescope in Chile, operated as part of the NASA-funded ATLAS survey, recorded an unfamiliar, rapidly moving speck.

Within hours, professional and amateur observers worldwide had combed archival data, tracing its motion back to at least June 14.

The collected positions fit a hyperbolic orbit – unmistakable evidence the object is diving in from beyond the Sun’s gravitational reach.

Richard Moissl, head of planetary defense at the European Space Agency, emphasized that 3I/Atlas poses no danger.

“It will fly deep through the solar system, passing just inside the orbit of Mars,” he said, adding that the flyby comes nowhere near a collision with Earth or the Red Planet.

Calculations show the interstellar comet will reach perihelion, its closest point to the Sun, on 29 October, then fade as it speeds back into the darkness over the next few years.

How interstellar comets differ

Unlike comets bound to the Sun, interstellar objects are born around distant stars. Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard–Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics explained the likely origin scenario.

“We think that probably these little ice balls get formed associated with star systems. And then as another star passes by, tugs on the ice ball, frees it out. It goes rogue, wanders through the galaxy, and now this one is just passing us,” he said.

In 2017, astronomers found the first known example, 1I/ʻOumuamua, whose odd shape and tumbling motion sparked contentious debate – including speculation it might be alien technology.

Two years later came 2I/Borisov, a more conventional comet with clear gas jets. 3I/Atlas now becomes the largest and fastest of the trio, offering scientists a fresh specimen to study.

Observations of a fast-moving comet

The MPC initially labeled the body A11pl3Z, but the “3I” prefix signifies its confirmed interstellar status. As data pours in, researchers aim to refine its orbit, rotation rate, and composition.

Scientists are particularly eager to learn whether its chemistry differs from solar system comets, which would provide clues about its natal environment.

Despite enthusiasm, a spacecraft intercept is beyond reach, since there is not enough time to plan, launch, and meet with an object moving this quickly and appearing on such short notice.

Ground-based and space-based telescopes will therefore carry the observational load, capturing spectra and high-resolution imagery while the interstellar comet remains within range.

Interstellar objects may be common

Mark Norris, an astronomer at the University of Central Lancashire, pointed out an intriguing statistic: modeling work suggests up to 10,000 interstellar objects could be drifting inside the solar system at any given moment – most of them too small or faint to detect.

The newly built Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, scheduled to begin its wide-field survey soon, is expected to uncover many more. Such a flood of discoveries would transform the study of planetary system formation.

Each passerby carries a chemical and physical record of processes that occurred around alien suns. They deliver natural “samples” at no cost other than the telescopic time required to study them.

Fly-by science in action

Scientists will watch 3I/Atlas brighten through the northern autumn, hoping for unobstructed views of its coma chemistry.

Spectrographs on large telescopes may reveal ratios of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and water vapor – benchmarks that help distinguish comets formed under different conditions.

Photometric monitoring can nail down its spin. Careful astrometry will improve the orbit and may even hint at non-gravitational forces from asymmetric outgassing.

Improving planetary defense capabilities

Beyond pure science, each interstellar detection enhances planetary defense capabilities.

Rapidly identifying an object’s orbit and assessing any hazard is a rehearsal for future surprises – though, happily, none of the known interstellar visitors have posed a threat.

For now, astronomers relish the serendipity. A cosmic snowball born around an unknown star has swung through humanity’s celestial neighborhood, offering a fleeting chance to study matter forged in a far-off corner of the galaxy.

With upgraded surveys on the horizon, the odds of such encounters – and the insights they carry – are only set to increase.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–