Invasive termites are interbreeding and creating a more destructive and resilient species

Florida homeowners have learned to keep watch for wood dust, yet the latest alert sounds different. Two separate termite invaders have started a family, and the offspring could march far beyond state lines.

Associate Professor Thomas Chouvenc of the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UFIFAS) spent years noting odd courtship dances between Formosan and Asian subterranean termites.

His new genetic survey confirms that those dances produced hybrids and that the young colonies are already sending winged scouts into the air.

Hybrid termites enter the scene

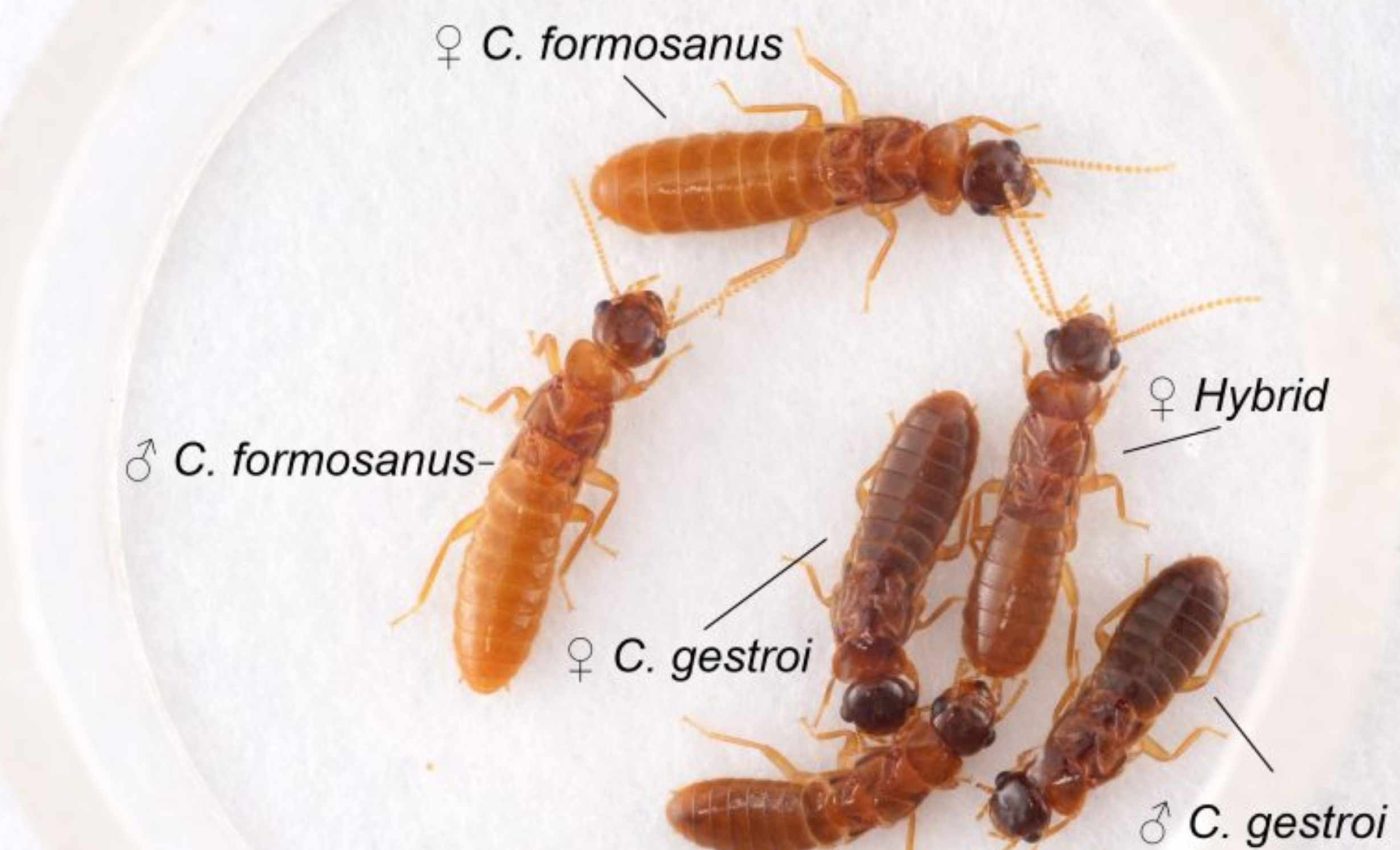

Both parents, Coptotermes formosanus and C. gestroi, rank among the world’s top structural pests, each with colonies topping two million workers and an annual United States repair bill near one billion dollars. Their hybrid offspring inherit twice the genetic playbook for gnawing through cellulose.

“We have confirmed the presence of hybrid swarms every year since 2021, including in April 2025,” says Chouvenc.

The discovery rests on field collections from Fort Lauderdale, where every spring since 2021 researchers have captured swarms that do not match either parent species, then confirmed mixed DNA in the lab.

That persistence signals a stable population rather than a one off incident. The study labels the event introgressive hybridization, a process that can speed evolution when separated lineages suddenly meet.

Two invaders are worse than one

Each parent species forms sprawling underground galleries that let workers chew through a foot of two by four pine in roughly six months. Combining that appetite with larger hybrid brood sizes could overwhelm local control efforts.

Laboratory tests show that first generation hybrid queens can backcross with males from either original species, opening the door to second generation mixes that might pick up even more survival tricks.

The team also notes that hybrid alates emerge at dusk when humid winds rise, a timing that maximizes dispersal and pairs easily with the yacht traffic common along Florida’s coast.

Chouvenc warns, “This may be a Florida story now, but it likely won’t stay just in Florida, give it time.”

The warning carries weight because adult alates can ride prevailing winds twenty miles or stow away on wooden pallets, boats, and nursery stock bound for distant ports.

The cost of hybrid termites

Formosan colonies alone have emptied homeowner wallets in New Orleans, where the pest costs an estimated three hundred million dollars a year in damage and treatment. The hybrids threaten to export that expense to every Gulf state and eventually the Mid Atlantic.

Unlike drywood termites, these subterranean colonies keep contact with the soil, sip water through mud tubes, and can attack wooden frames, live trees, and even foam insulation. Insurance rarely covers termite damage, leaving families to foot the repair bills.

City managers also fret over infrastructure because the insects tunnel under sidewalks and hollow utility poles. An untreated infestation can topple a mature oak, creating both public safety hazards and hefty removal fees.

Hybrid termites and climate change

Termites do more than eat houses; their gut microbes pump out methane, a greenhouse gas thirty times more potent than carbon dioxide over a century.

Global estimates place termite methane at one to three percent of natural sources, roughly twenty million tons each year.

Field research in northern Australia shows that termite mounds can trap about half of that gas before it escapes, but subterranean colonies lack such filters and vent straight into the air.

More colonies, especially in warming regions where the insects thrive, could nudge emissions higher.

Researchers in Louisiana and Brazil report that colonies increase feeding rates at temperatures above 77 degrees Fahrenheit, suggesting warmer states could see faster wood turnover and even higher methane release. Higher energy demands inside each colony translate into more gas expelled per worker.

Scientists already predict termites will expand poleward as winters soften. Hybrid vigor may accelerate that march, giving the insects tolerance for cooler nights and broader diet choices.

What scientists can and cannot do

Chouvenc’s group can monitor flight seasons, map nest distribution, and test baits, yet they cannot stop wild mating flights.

Once a male and female land in damp soil, they seal themselves inside a starter chamber, shed their wings, and vanish from view.

Chemical barriers around foundations help, but rainfall and shifting soils create gaps big enough for a worker as thin as a credit card to slip through.

Baits laced with chitin synthesis inhibitors work better because returning workers share the toxin with nestmates, collapsing the colony quietly.

Regulators consider introducing natural enemies risky, as past biological control attempts sometimes harmed native insects. For now, the strategy focuses on early detection and public education.

Protecting homes and forests

Home inspectors recommend removing firewood piles, trimming shrubs away from siding, and fixing leaks that keep soil moist.

Simple steps reduce the chemical footprint and buy time for researchers to refine next generation baits that exploit hybrid genetics.

Marine surveyors now inspect hulls and wooden crates before granting port clearance, trying to cut off oceangoing “termites as stowaways,” as one expert called them. Similar protocols could appear at rail hubs if inland incursions begin.

Good record keeping matters too. When contractors document infestation dates, treatment types, and reinfestation intervals, entomologists can model spread patterns and plug weak spots in the defense grid.

Looking ahead

Hybrid termites remind us that invasive species do not stay within political borders. Global trade, climate shifts, and urban sprawl give them tickets to ride.

The question is not whether the hybrids will reach new zip codes but how prepared those zip codes will be when the first alates flutter down. As Chouvenc quips, “Give it time.”

The study is published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Photo credit Thomas Chouvenc.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–