Leg bones found from a massive meat-eating 'terror bird' that lived 12 million years ago

Twelve million years ago, a huge flightless predator known as a “terror bird” sprinted across tropical floodplains in what is now central Colombia.

Archaeologists discovered a single broken leg bone – evidence that turns a fragment into a clear view of life in the Miocene.

The study was led by Federico J. Degrange, a terror bird specialist, and included Siobhán Cooke, Ph.D., associate professor of functional anatomy and evolution at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The fossil comes from the Tatacoa Desert, a dry landscape today that once held broad, meandering rivers lined with forests and wetlands.

Monkeys lived in the canopy. Hoofed mammals moved across open ground. Giant ground sloths and armored glyptodonts – about the size of a small car – shared the scene. A top predator fit right in.

Understanding terror birds

Terror birds, or Phorusrhacidae, were large, flightless, meat-eating birds tuned for running rather than flight.

They carried heavy, hooked beaks for seizing prey and long, powerful legs that made speed their edge on land. They shaped South American food webs for much of the Cenozoic.

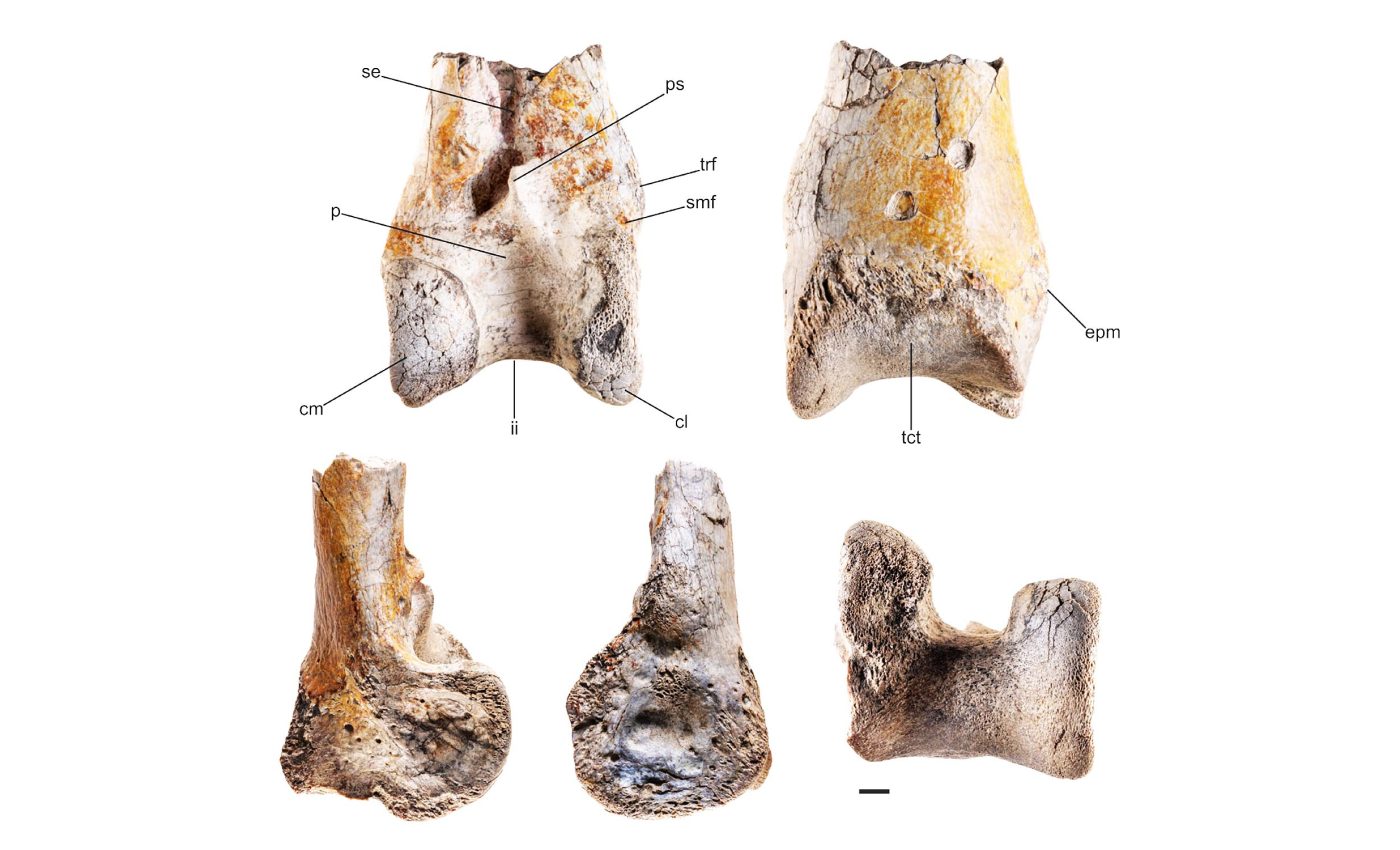

This Colombian fossil is just the distal end of a left tibiotarsus, the main lower leg bone in birds.

That part of the skeleton preserves deep pits and ridges where ligaments and tendons anchored, along with the joint surface that connected to the ankle joint.

Those features point squarely to a terror bird, not a plant-eating bird or a crocodilian.

Fragments tell tales

Researchers scanned the bone and built a high-resolution 3D model to measure it without damage. They compared it with terror bird fossils from farther south.

The virtual model made size estimates possible and allowed close anatomical matches.

The La Venta fossil site provides precise geographic and geologic context, anchoring the bone in the middle Miocene of tropical northern South America. That gives the specimen both an address and a date.

Scaling the bone against other species pointed to the same result: this terror bird was roughly five to twenty percent larger than the biggest confirmed terror birds in the fossil record.

“Terror birds lived on the ground, had limbs adapted for running, and mostly ate other animals,” Cooke says. Previously discovered fossils indicate that terror bird species ranged in size from 3 feet to 9 feet tall.

Picture a runner reaching the height of a basketball hoop, with legs built to accelerate fast on open ground.

Modern seriemas, long-legged ground hunters native to South America, offer a living echo. They are much smaller and lighter. Terror birds were the bulked-up apex version from millions of years earlier.

Terror birds had wide ranges

Most well-known terror bird fossils come from Argentina and Uruguay. A specimen in Colombia pushes their range north and shows they thrived in tropical lowlands as well.

They were not limited to the Southern Cone; they occupied a broad swath of the continent.

That range expansion shifts how we read Miocene ecosystems in northern South America. These places supported huge, fast terrestrial birds near the top of the food chain, not just herbivores and mid-level carnivores.

Clash at the water’s edge

The tibiotarsus fragment preserves a round, tooth-shaped gouge and other damage that look like bites. The likely biter was Purussaurus, an extinct giant caiman that could grow longer than a pickup truck – up to 30 feet long.

The bone records predator-versus-predator action, whether an ambush at the river margin or scavenging after death.

“We suspect that the terror bird would have died as a result of its injuries given the size of crocodilians 12 million years ago,” Cooke says.

Direct evidence like this moves us from a list of animals to a record of interactions. It shows who did what to whom.

One bone holds lots of information

In paleontology, certain bones pack dense information about identity and performance. The tibiotarsus is one of them.

Because terror birds were runners, their leg joints evolved to handle high forces during sprinting and turning. Those shapes differ from the joints of waders, perchers, or strong fliers.

With diagnostic anatomy in hand, scientists apply established scaling relationships to estimate body size.

Combine that with reliable site data, and the picture sharpens: a giant, fleet predator in the middle Miocene of Colombia.

South American landscape

Before the Isthmus of Panama connected the continents, tropical South America held both water and land dangers: large crocodilians in rivers and lakes, and fast terrestrial hunters on floodplains.

With a top bird predator confirmed in the north, models of ancient food webs gain a crucial data point.

Prey species faced pressure from different directions, shaping growth rates, movement patterns, feeding times, and escape strategies.

Context matters here. The Miocene was a time of changing climates and shifting habitats. A large runner on land and a giant caiman in the water show how layered those ecosystems were.

Old bones, new tools

This bone sat in a regional collection for years before anyone recognized it as part of a terror bird.

A portable scanner and modern imaging made non-destructive study possible and let collaborators examine the model from anywhere.

That approach – local collections paired with digital tools – is speeding up discoveries across museums.

It’s not just new digs that change our understanding. Looking again at what we already have can be just as powerful.

“It’s possible there are fossils in existing collections that haven’t been recognized yet as terror birds because the bones are less diagnostic than the lower leg bone we found,” she says.

For Cooke, the finding helps her imagine an environment one can no longer find in nature.

“It would have been a fascinating place to walk around and see all of these now extinct animals,” she says.

Terror birds, dedication, and some luck

Finds like this come together because many people do their part. A curator spots something that others overlooked.

Field notes and careful labels keep the specimen tied to time and place. Specialists in anatomy, imaging, and ancient environments pool their skills to test ideas against the evidence.

The result is more than a size record. It’s a clearer story of life and death in a green Miocene world where a giant, flightless “terror bird” thundered along riverbanks, wary of crocodilian jaws and ready to sprint down prey.

If you think the South American jungles are a scary place now, stop for a minute and imagine what it was like 12 million years ago when the terror birds and Purussaurus ruled.

The full study was published in the journal Paleontology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–