Long-dead satellite emitted an incredibly powerful radio pulse, baffling astronomers

A satellite launched when slide rules still ruled has jolted astronomers in 2025. NASA’s Relay 2, silent since the summer of 1967, fired off a single radio pulse so bright it briefly eclipsed every cosmic source above Earth.

Clancy James of Curtin University in Perth and colleagues stumbled on the flash during a routine search for fast radio burst signals.

Old hardware, new mystery

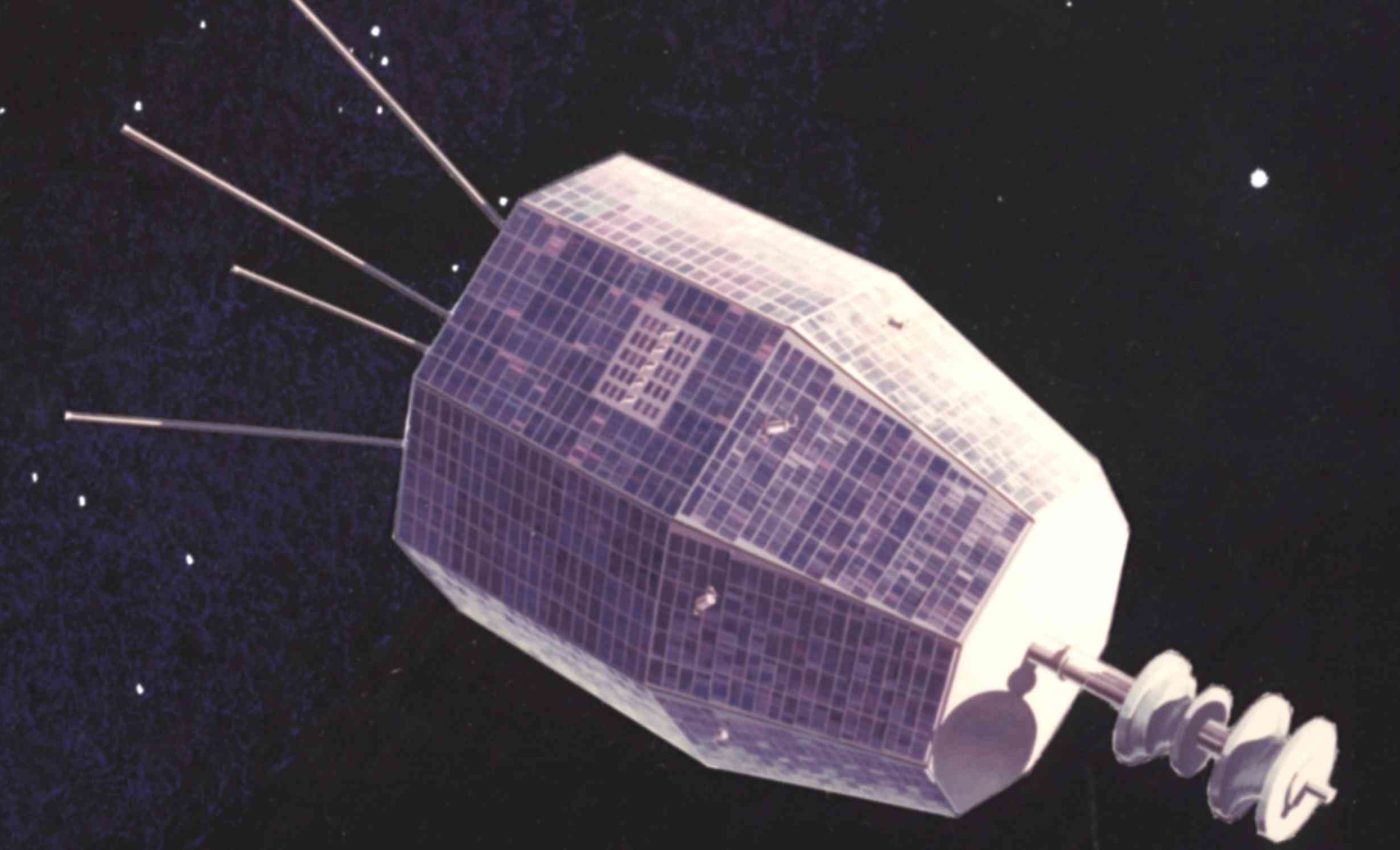

Relay 2 left Cape Canaveral on January 21, 1964 as an experimental communications craft, then slipped into bureaucratic oblivion once its battery failed.

NASA’s archival record shows the carcass still loops along an orbit ranging between 1,160 and 4,750 miles above the surface.

On June 13, 2024 Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) registered a 695.5-to-1031.5 MHz spike that saturated the array’s detectors.

The burst’s dispersion measure, essentially a fingerprint of electrons along its path, matched a single hop through the ionosphere, telling the team the culprit was local rather than interstellar.

“If it’s nearby, we can study it through optical telescopes really easily, so we got all excited, thinking maybe we’d discovered a new pulsar or some other object,” said James.

ASKAP’s software could not focus properly because the source lay close, inside a 12,400-mile shell around Earth.

Catching a nanosecond flash

“That was an incredibly powerful radio pulse that vastly outshone everything else in the sky for a very short amount of time,” added James.

The team rebuilt the signal with sub-nanosecond precision and found it lasted under 30 ns while pumping at least 300 kilojanskys of flux, millions of times the brightness of Jupiter at radio wavelengths.

ASKAP excels at rapid wide-field surveys and normally hunts distant galaxies. Its 36 twelve-meter dishes, spread over six square miles of Western Australia, feed a supercomputer that digests 100 trillion bits per second.

Because ASKAP triangulates sources, the group compared time delays across dishes and nailed the origin to Relay 2’s predicted track. No other satellite sat within the narrow uncertainty cone at that instant.

What could light up a corpse in orbit

Relay 2 carries no active transmitters, so the flash must have come from an external trigger. The leading suspect is an electrostatic discharge, a spark leaping between charged surfaces after the craft rubbed against plasma in low Earth orbit.

Spacecraft charging worries engineers on the International Space Station, where analyses show stray arcs can jolt metal tools and even astronauts during spacewalks.

The same physics applies to derelict aluminum shells tumbling through Earth’s shadow and sunlight several times a day.

A rival idea invokes a tiny micrometeoroid striking the satellite at about 22,000 mph, instantly vaporizing metal and creating an expanding plasma cloud that radiates radio noise.

Particles smaller than a pea pepper thousands of spacecraft annually, and shielding against them is limited on old buses like Relay 2.

“In a world where there is a lot of space debris and there are more small, low-cost satellites with limited protection from electrostatic discharges, this radio detection may ultimately offer a new technique to evaluate electrostatic discharges in space,” said Karen Aplin of the University of Bristol, who was not involved in the study.

Why short radio pulses matter

Bursts this short push detectors to their limits, highlighting a blind spot in modern transient surveys. Most instruments record millisecond snapshots, so any comparable events elsewhere in the sky would have slipped past unnoticed until now.

A single nanosecond pulse contains frequency components up to gigahertz levels, revealing fine structure in the ionosphere when it passes through.

That makes each flash an unintended probe of Earth’s upper atmosphere, much like lightning strokes map thunderstorms.

The new detection also reminds astronomers that local clutter can masquerade as cosmic treasure. Search pipelines looking for extragalactic fast radio burst events must now filter out possible shots from derelict satellites, lest they misclassify Earth-orbiting sparks as distant magnetars.

Debris, satellites, and hidden hazards

More than 29,000 tracked objects crowd low Earth orbit, and millions of fragments smaller than a marble remain invisible to radar. A metric-ton satellite built in the Apollo era was never screened for today’s debris environment.

Micrometeoroids travel so fast that even a flake of paint can punch dime-sized craters in solar panels. NASA modeling shows a one-centimeter chip at hypervelocity matches the kinetic energy of a 550-pound weight dropped at 60 mph on Earth.

If such an impact occurred on Relay 2, vaporized aluminum and solar-panel glass would briefly ionize, setting up currents that ring like a bell in radio.

The ASKAP detection suggests this clang can be loud enough to outshine the entire sky, at least for a few billionths of a second.

What happens next

James’s group is developing software triggers so ASKAP will save raw voltages when a nanosecond flash hits, preserving more detail.

Parallel efforts are under way at the Canadian CHIME and South African MeerKAT arrays to watch known dead satellites during meteor showers.

Engineers welcome the possibility of passive monitoring. Real-time radio surveillance could flag electrostatic discharge events on active spacecraft and warn operators before cumulative damage builds.

At the policy level, agencies may need to include radio-quiet zones in licensing rules, preventing future constellations from producing spurious flashes that muddy astrophysical data.

The Relay 2 episode proves even silent satellites can still speak, just not on purpose.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–