Medieval volcanic eruptions may have sparked the deadliest plague in human history, killing tens of millions of people

The Black Death tore through Europe in the late 1340s, killing tens of millions and halving populations across the continent in a matter of years.

Scientists have long known the plague’s culprit was Yersinia pestis, which is carried by fleas and rats. However, what is still up for debate is how the pandemic moved so swiftly across medieval Europe, and why the it ignited when it did.

Black Death and volcanic eruptions

A new study published in Communications Earth & Environment suggests the spark for the Black Death plague may not have come solely from war or commerce, but from climate conditions caused by volcanic eruptions.

The researchers argue that two unusually cool summers, which may have been caused by layers of volcanic ash in the atmosphere, ultimately disrupted harvests across the Mediterranean.

These dramatic climate events then forced desperate Italian city-states to reopen grain routes to the Black Sea, just as the Black Death plague was circulating there.

“It’s adding a piece to the puzzle we did not previously have,” Hannah Barker, a historian at Arizona State University who was not involved in the study, told Science. “People hadn’t looked at climate before when it came to the Black Death.”

Tree rings and climate cooling

The research team picked up the trail by studying wood and ice from that time period. Study co-author Ulf Büntgen, a dendrochronologist from the University of Cambridge, noticed that trees in the high Pyrenees struggled to grow in the summers of 1345 and 1346.

Tree rings during that period show a fingerprint of unusual cold weather during those growing seasons, and eight more tree ring records from Europe echoed those signals found in the Pyrenees.

Those same years, ice cores from Greenland and Antarctica captured spikes in sulfur, the airborne residue of volcanic eruptions that loft sun-dimming particles into the stratosphere.

“The summer temperature isn’t extreme, but it’s cold – and it’s two years in a row,” said Büntgen. “That’s likely the result of a cluster of sulfur-rich volcanic eruptions.”

Harvests falter across Europe

The historical written record reflects the mood on the ground. Chroniclers from Japan to France noted persistently cloudy skies between 1345 and 1347.

In Italy and its hinterlands, harvests faltered in 1345 and 1346, while grain prices shot to their highest in eighty years. As stocks dwindled in early 1347, unrest simmered in the great city-states.

“In the sources you can see governments panicking and trying to figure out what to do,” Barker noted.

Venice and Genoa were not passive actors in the food trade. By the 14th century, they ran far-flung procurement systems and spent heavily on strategic reserves.

But geopolitics boxed them in: since 1343, they had been at war with the Mongol Empire over Black Sea access, severing a critical grain lifeline.

Desperation reopens trade

Cooling across the Mediterranean tightened the situation. With Sicily, Spain, and North Africa also squeezed by poor yields, Italy’s maritime republics were cornered.

“In 1347, they were forced to make peace with the Mongols because they felt the pressure of dwindling food supplies,” said study co-author and historian Martin Bauch.

Within months, grain galleys were again departing from Black Sea ports in Crimea and along today’s Ukrainian coast, their holds crammed with wheat, the study argues, unwittingly with plague as well.

Black Death, volcanic ash, and grain

How does a bacterium hitch a ride in bulk cargo? Sparse but telling reports suggest plague had been afflicting Mongol forces in the region for years.

Researchers propose that when the embargo lifted, the wheat shipments also imported fleas carrying Yersinia pestis, possibly feeding on grain dust, noted Büntgen.

Once dockside sacks were opened and stores distributed, the fleas needed only to jump to local rats and, from there, to people.

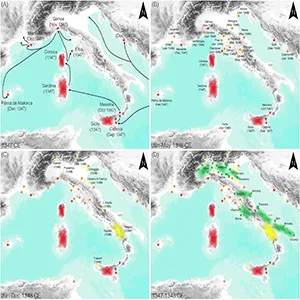

The epidemic’s pattern fits the supply chain: Venice and Genoa, regions that depended on imported grain, saw plague hit their lands first. Inland cities with stronger local harvests, like Rome and Milan, faced it later.

“It’s a very early ramification of globalization,” said Büntgen. “Trade helps it spread.”

Conditions aligned for Black Death

To Timothy Newfield, a historical epidemiologist, the work highlights just how contingent the Black Death was.

“These results make the Black Death seem like even more of an anomaly,” he said. “It really demonstrates how many variables had to line up for the Black Death to start.”

The pathogen had to be circulating in the Black Sea zone. The climate shock had to be strong enough – and sustained over back-to-back summers – to upend Mediterranean harvests.

The Italian city-states had to accept peace with the Mongols at precisely the wrong moment. And then maritime logistics had to do what they always do: move huge quantities of food rapidly across long distances.

Climate enters the narrative

None of this dethrones Y. pestis as the engine of catastrophe or minimizes the roles of warfare, poverty, and urban crowding.

But it adds climate to the prelude in a concrete way: not as a vague backdrop, but as a direct shove that reconfigured supply lines.

Volcanic aerosols dimmed sunlight, crops faltered, grain markets convulsed, and shipping lanes reopened to the very ports where plague lurked. In that sense, the study does not just revise a medieval story; it highlights a modern one.

Earth’s food, health, and financial systems are interlocked. A perturbation in one domain can cascade into another, and commerce can transform local hazards into continent-sized disasters with startling speed.

Black Death lessons from volcanic eruptions

Tree rings and ice cores cannot name the volcanoes involved or isolate the first flea to carry the plague. However, they can pinpoint the timing of the unseasonably cold weather in the region.

Those dates match written accounts of hunger and policy reversals that put Italian galleys back in the Black Sea in 1347.

The rest of the Black Death pandemic unfolded with grim efficiency, quickly spreading through a combination of volcanic shade, failed harvests, and desperate purchases.

Grain in the hold, fleas in the dust, plague in the streets.

Breaking it down in this way, the research team does not claim that climate change from volcanic eruptions directly caused the Black Death plague, but they believe it did set dominoes in motion.

The study is published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–