Moon-forming dust disk discovered around a massive planet

The James Webb Space Telescope just made another big catch – and this one might help explain how moons are made. Way out in space, about 625 light-years from Earth, there’s a young planet called CT Cha b. It’s not alone.

It’s surrounded by a thick, carbon-rich disk that might be building moons. While scientists didn’t find any moons in this observation, the stuff needed to make them is clearly there.

This is the first time we have taken a direct look at the chemicals and physical features of a disk like this – one that could actually be forming moons around a planet.

Moons in the making

We live in a solar system packed with moons. Some, like our own, just tag along quietly. Others might even have the right ingredients for life.

But when and how do these moons form? Until now, we’ve had theories, but not much direct evidence.

Now, thanks to the James Webb Telescope’s powerful infrared eyes, that’s changing.

CT Cha b orbits a very young star – only about 2 million years old. That’s extremely young in space terms. Both the planet and the star are still gathering material.

But here’s the twist: the planet’s disk isn’t just part of the leftover junk from the star.

CT Cha b sits a massive 46 billion miles away from its star – too far to be caught up in the same swirl of gas and dust. That makes this disk something special.

It’s forming on its own, around the planet, possibly cooking up moons in the process.

Studying CT Cha b with Webb

Researchers used Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) to look closely at CT Cha b. Even with Webb, that wasn’t easy.

The planet’s signal was faint and buried in the glare from the bright star. Scientists had to use special methods to separate the planet’s light from the star’s.

“We saw molecules at the location of the planet, and so we knew that there was stuff in there worth digging for and spending a year trying to tease out of the data. It really took a lot of perseverance,” said Sierra Grant of the Carnegie Institution for Science.

What they found made the effort worth it.

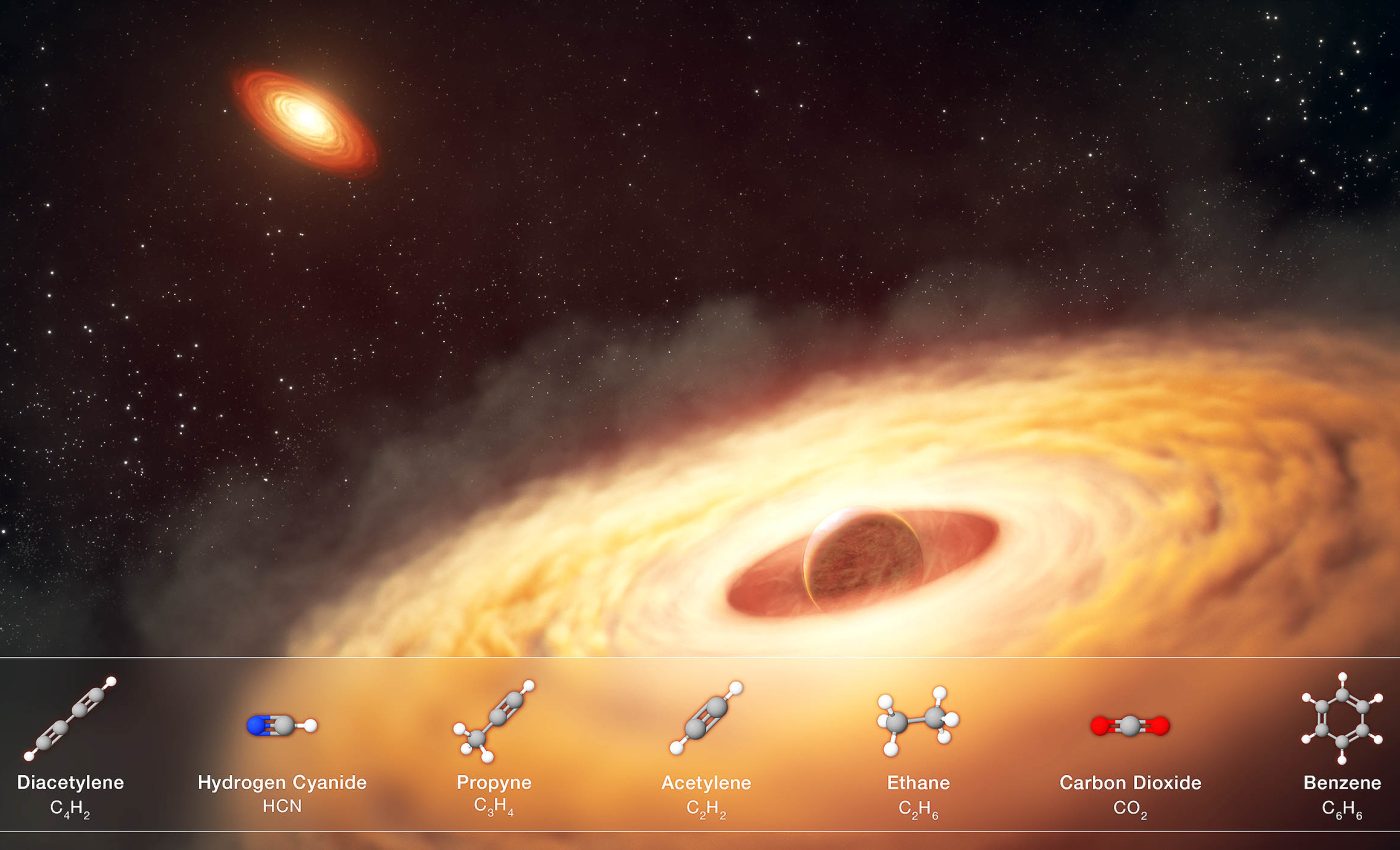

The telescope detected seven carbon-based molecules inside the planet’s disk, including acetylene (C₂H₂) and benzene (C₆H₆). These are both simple, carbon-rich molecules.

What’s more interesting is that this carbon chemistry is very different from the chemistry around the central star – that area has water but little carbon.

This sharp difference shows just how fast things can change in space. The planet and star formed around the same time, yet their surrounding disks already look very different.

Connecting the dots to Jupiter

This discovery leads into a much bigger question: how did the moons in our solar system form?

Jupiter’s four largest moons – the Galilean moons – likely formed from a circumplanetary disk like the one around CT Cha b. That idea isn’t new. But until now, no one had actually seen such a disk with this much detail.

“We are seeing what material is accreting to build the planet and moons,” said Gabriele Cugno of the University of Zürich.

The Galilean moons, especially Ganymede and Callisto, are half water ice. But they also seem to have rocky cores – possibly made of carbon or silicon.

That mix of ingredients points back to the kind of environment we’re now observing around CT Cha b.

“We want to learn more about how our solar system formed moons. This means that we need to look at other systems that are still under construction. We’re trying to understand how it all works,” said Cugno.

“How do these moons come to be? What are their ingredients? What physical processes are at play, and over what timescales? Webb allows us to witness the drama of moon formation and investigate these questions observationally for the first time.”

Lessons learned from CT Cha b

So far, CT Cha b’s disk doesn’t show any actual moons. But that doesn’t mean they won’t form. The materials are there. And scientists now have a real shot at catching future systems as they evolve.

The research team plans to use Webb again soon to scan other young planetary systems and see what kinds of disks they’re hiding.

By comparing different systems, they hope to understand how common – or rare – moon-forming disks really are.

Information from a NASA press release.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–