Multiple new species of 'living fossil' fish discovered that lived over 200 million years ago

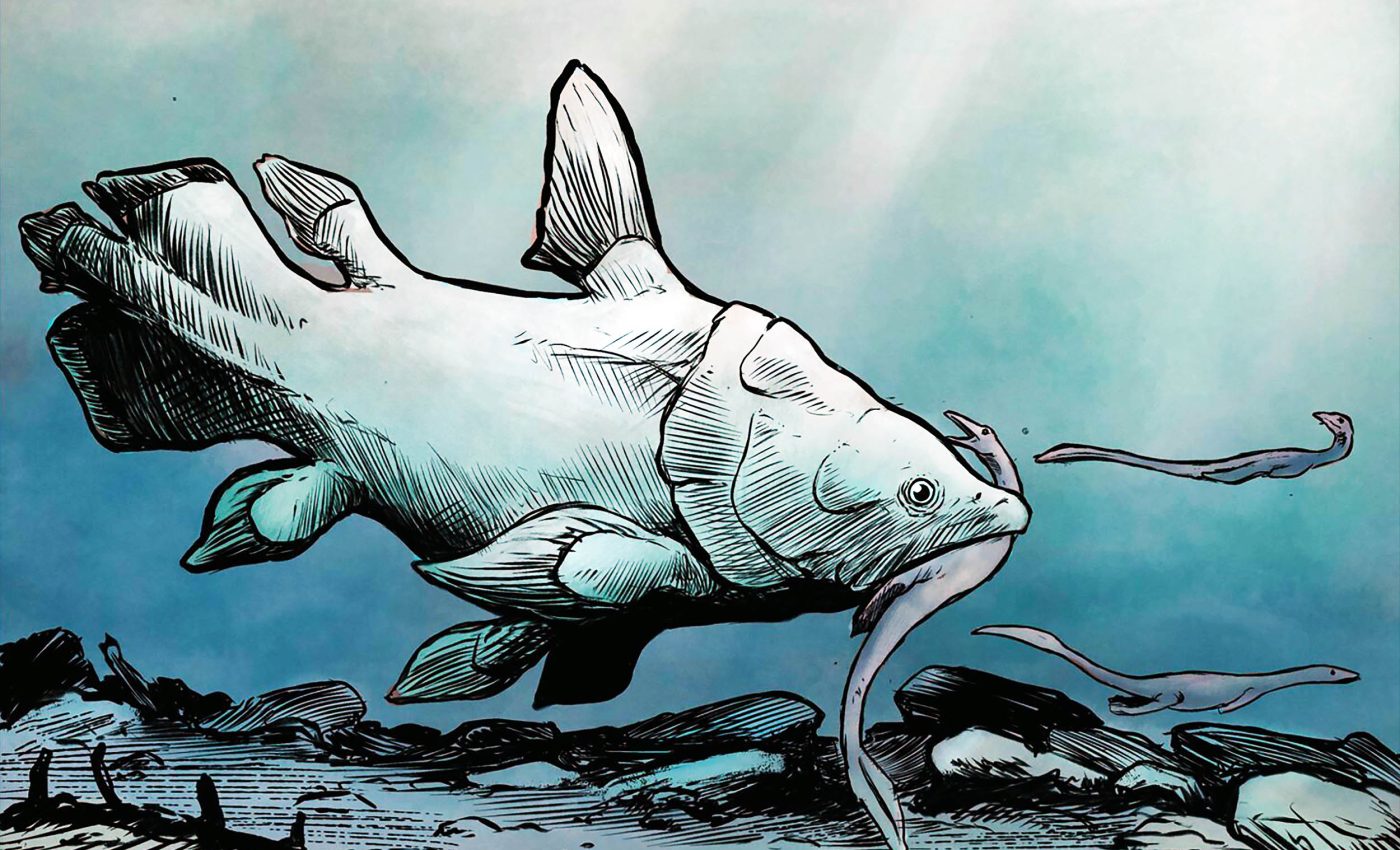

Modern sightings of living coelacanths in the 20th century surprised the world, but the species’ fossil story goes back a long way.

Although coelacanth remains are well known from Paleozoic and Cretaceous rocks in Britain, they are poorly known from the Late Triassic. A fresh look inside British museum drawers has just closed one of these gaps.

A new peer-reviewed study reports more than 50 late Triassic coelacanth specimens from southwestern England, many of them mislabeled for over a century. The lead author is Jacob G. Quinn from the University of Bristol.

Fossils reidentified as coelocanths

The researchers reidentified bones that were previously assigned to small marine reptiles, and even mammals, as parts of ancient coelacanth fishes.

Most belong to the Mawsoniidae, an extinct branch that is closely related to today’s species.

“From just four previous reports of coelacanths from the British Triassic, we now have over 50,” said Quinn.

Coelacanth success in Triassic

Living coelacanths sit in the genus Latimeria, and their lineage reaches back hundreds of millions of years. Finding a diverse spread of late Triassic bones in Britain shows the group was doing well along near shore habitats at the time.

Prior analysis of Mawsonia (a giant, prehistoric coelacanth) and its relatives gives ecological signals that mawsoniids often favored brackish or fresh water settings, which fits the shallow coastal picture.

Fossils mislabelled for decades

Many of the newly recognized bones had been filed under Pachystropheus, a small thalattosaur from the same rocks.

The confusion makes sense because isolated skull and jaw parts can look similar when time and abrasion wear them down.

“During his Masters in Palaeobiology at Bristol, Jacob realized that many fossils previously assigned to the small marine reptile Pachystropheus actually came from coelacanth fishes,” said Professor Mike Benton from the University of Bristol.

That realization prompted a tour of museum collections across the country to check labels and compare anatomy.

Life on Triassic shores

These fossils come from the Rhaetian stage, the very end of the Triassic, when the Bristol Channel area was a chain of low islands in a shallow, tropical sea.

The rock unit, called the Westbury Formation, preserves storm-swept layers known as bone beds.

Those layers trap a jumble of fish, reptiles, and plant spores that point to coastlines and wetlands close by.

The coelacanth bones frequently appear with Pachystropheus, which suggests both lived and fed near the seafloor.

Scans proved coelacanth bones

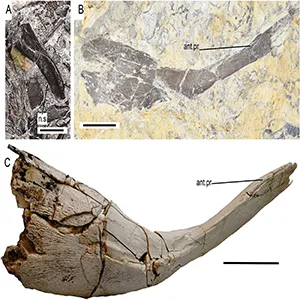

The team used micro-CT to peer inside several dense bones and map tiny canals for nerves and blood vessels. Those internal features match coelacanth anatomy, which helped separate fish pieces from reptile lookalikes.

They also compared the shape and surface texture of jaw and cheek bones with published descriptions of coelacanth species.

Subtle patterns, like the position of sensory canals and the form of joint surfaces, helped sort mawsoniid from latimeriid traits.

A mix of species was present

A robust clavicle, the largest single piece in the sample, hints at hefty fish moving along the Triassic coast. Other skull parts show a spread of sizes and ages, suggesting an actual community rather than a one-off carcass.

The paper documents multiple morphotypes for key bones, which likely means several species lived side by side.

It also means earlier workers were not wrong to hesitate, because isolated pieces can have changed shape with growth and wear.

Old labels hid true identity

Several specimens had sat in drawers since the late 1800s with names that made sense at the time. Early collectors did not expect to find coelacanths in these beds and often settled on more familiar reptile labels.

This study shows how curation, careful re-examination, and new imaging can turn old material into new science. It also highlights the value of detailed locality notes, which help connect a bone to a specific layer and environment.

Slow coelacanth evolution

Coelacanth bones are conservative in shape, so species level IDs are hard when only fragments survive.

Even so, the basisphenoid and jaw elements unearthed fit the mawsoniid pattern that becomes common later in the Jurassic and Cretaceous.

That continuity supports a slow changing head plan over tens of millions of years. It also strengthens the case that European coelacanths radiated along shorelines where rivers met the sea.

Where the living fish fits in

The living coelacanth story often starts in 1938 with a South African trawl and a phone call from a museum curator. An Indonesian population entered the record soon after.

Those modern sightings frame a lineage that survived in deep marine caves while its fossil cousins patrolled coastal flats.

The new British material fills a key moment just before the end Triassic crisis, when ecosystems were shifting fast.

This is a case study in how science self-corrects with new methods and fresh eyes. It also shows that museum collections are active research tools, not just shelves of curiosities.

The study is published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–