Mummified cheetahs that lived 4,000 years ago found perfectly preserved in desert caves

Seven cheetah mummies – some thousands of years old – have been uncovered in caves in northern Saudi Arabia. They are the first naturally mummified big cats ever documented, preserving soft tissue as well as bone and rewriting the species’ deep history on the Arabian Peninsula.

Alongside them were the skeletons of dozens more cheetahs, hinting at a long, complicated relationship between these predators and the region’s harsh desert landscapes.

The discovery comes from surveys of the Lauga cave network carried out in 2022 and 2023.

A team led by Ahmed Boug at the National Center for Wildlife in Riyadh reported seven mummified cheetahs and the skeletal remains of 54 others, spread across five caves.

The mummies span an extraordinary window in time, dating from roughly 4,000 years ago to about a century ago, offering a rare layered record of a species that disappeared from Arabia decades ago.

How to make cheetah mummies

Natural mummification needs the right recipe: stable temperatures, very dry air, and little disturbance. That is exactly what these caves provide.

The relatively constant temperature and low humidity of the cave environments would have been conducive to the mummification process.

Unlike deliberate embalming, the process here halted decay on its own, leaving skin and other soft tissues intact on some remains.

For cheetahs, which are not cave dwellers by habit, ending up underground is a mystery in itself. None of the five caves had water when surveyed, and cheetahs aren’t known to stash carcasses in caverns.

One cave, however, is entered through a sinkhole – an easy trap for a sprinting cat in the wrong place at the wrong time. It’s possible some animals fell in and couldn’t escape.

Arabian caves collected predators

The cheetahs weren’t alone. Bones from a wolf, striped hyena, gazelle, and red fox turned up in the same system, suggesting the caves have been accidental collectors for centuries.

Modern camera traps set during the surveys caught wolves moving through, proof that at least some entrances have been accessible during the cheetahs’ time.

According to the research team, the caves were accessible during the mummified cheetahs’ lifetimes and that the cheetahs could have deliberately entered them.

When researchers examined 20 complete cheetah skulls, they counted six adults. The rest belonged to juveniles, roughly six to 24 months old.

In the main cave, the experts also found the remains of nine cubs. That age spread is intriguing.

Cheetahs are solitary hunters, but mothers shelter and move their young frequently.

The presence of so many young animals underground hints that adult females may have used some of these spaces as temporary refuges, especially during heat, storms, or threats from larger carnivores.

Cheetahs are the first big cat mummies

“The findings are truly remarkable,” Anne Schmidt-Küntzel, from the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia, told New Scientist.

“In itself, the mummification of a felid is not entirely surprising, but it remains a first and, with that, a very important finding.”

Natural mummies of large predators almost never survive, particularly in hot climates. These do more than astonish, they anchor timelines and preserve DNA and soft tissue for study.

The mummies also reveal that cheetahs persisted in Arabia far longer – and perhaps in larger numbers – than the scattered historical records suggest.

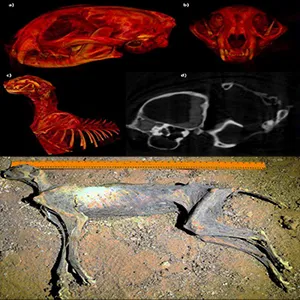

Scans and genome sequencing

Boug’s team sequenced the genomes from three individuals. The youngest mummy, more recent in age, appears closest to the Asiatic cheetah, the critically endangered subspecies now lingering in Iran.

That makes geographic sense; Iran is the nearest place where cheetahs survive today.

The surprise came from two older samples, about 3,000 and 4,000 years old, which showed affinities with the northwest African subspecies.

That genetic fingerprint implies ancient connections and movements across North Africa and the Middle East, when landscapes and human pressures were different from today.

Reintroduction to Arabia

Why so much cold, dry-preserved cheetah material exists so close together is still up for debate. The sinkhole cave could have acted like a natural pitfall over millennia.

Predators might have chased prey into tight spaces and found themselves trapped. Contrary to textbook behavior, female cheetahs may have sometimes used caves to shelter their young when outside threats mounted.

What is clear is that the Arabian interior has quietly held onto a fossil record that conservationists and archaeologists can now read with modern tools.

Although there is only one cheetah species, it has four genetically distinct subspecies, with the southeast African cheetah being the most numerous today.

The new work bolsters a practical idea. Cheetahs used Arabia for thousands of years, and different subspecies tolerated its arid conditions.

Researchers could plausibly reintroduce captive-bred animals from robust African lineages in the future, provided careful planning restores habitat and prey.

Schmidt-Küntzel notes that the findings support the notion that cheetah subspecies can adapt to the same dry environments, strengthening the case for that approach.

Cheetahs, mummies, and Arabian caves

Cheetahs once ranged from southern Africa across the Sahara and the Middle East into India. Habitat loss, hunting, and trade pushed them into retreat, and they vanished from the Arabian Peninsula within living memory.

The Lauga caves carry their story across four millennia: a female and her cubs sheltering from a dust storm; a young cat tumbling through a sinkhole; a lineage shifting as climates and human footprints changed.

These natural mummies, along with the dozens of bones around them, turn that elegy into evidence. For science, the caves are a rare archive – part museum, part graveyard, part genetic library.

For conservation, they are a reminder that landscapes can hold surprises and that species with enough room and prey can find ways to persist.

In that sense, the cheetahs of Lauga are both a message from the past and a nudge about the future.

The study can be found in the preprint archive Research Square.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–