NASA finds a cosmic monster so bright it breaks the rules of physics

Astronomers using NASA’s NuSTAR X-ray telescope have confirmed that a compact star named M82 X-2 shines about 10 million times brighter than the Sun, apparently pushing past a long trusted brightness limit in physics.

The object sits in the nearby galaxy M82, about 12 million light years away, roughly 70 quintillion miles, and its fierce X-rays have puzzled observers for years.

Now researchers have shown that this source really does exceed the usual cap on how bright a star-sized object should be, instead of only looking brighter because of a viewing trick.

NuSTAR‘s analysis ties that extreme light to a torrent of stolen matter and to magnetic fields so intense that they change how atoms behave near the star.

X-rays from M82 X-2

The work was led by Matteo Bachetti, an astrophysicist at the National Institute for Astrophysics’ Cagliari Observatory in Italy (INAF). His research focuses on ultraluminous X-ray sources, extremely bright X-ray systems in other galaxies.

A broad review of these sources finds that they typically shine with more than 10^39 ergs of X-ray power each second, far above normal X-ray binaries powered by stellar mass black holes.

These objects usually sit away from the centers of galaxies, and many cluster in regions where new stars are forming quickly.

The key idea behind their mystery is the Eddington limit, the maximum steady brightness an object can reach before its own light should blow away the gas that feeds it.

At that point, gravity pulls inward while outgoing radiation pushes outward so strongly that further infall of matter should stall.

For years many astronomers guessed that ultraluminous X-ray sources must hide unusually massive black holes, because heavier objects have higher Eddington limits and could shine so strongly without breaking the rule.

The discovery of regular X-ray pulses from several ULXs, including M82 X-2, showed that at least some are not black holes at all but spinning neutron stars with solid surfaces.

Tiny star with absurd power

M82 X-2 is a neutron star, the compact leftover core of a massive star that exploded as a supernova. The whole object packs more mass than the Sun into a ball only about as wide as a large city.

Because so much matter is squeezed into such a small volume, its surface gravity is about 100 trillion times stronger than the gravity you feel at Earth’s surface.

That kind of pull means infalling gas slams into the surface at millions of miles per hour and is heated to X-ray emitting temperatures.

NASA estimates that this star is gobbling roughly 9 billion trillion tons of gas every year from its partner star, which works out to about one and a half times Earth’s mass per year.

That furious feeding frenzy releases more energy than a thousand hydrogen bomb blasts would, even if it came from something as small as a marshmallow sized lump of material hitting the surface.

Taken together, the measured energy output appears to be 100 to 500 times brighter than the Eddington limit for a typical neutron star of this mass.

That is why M82 X-2 is often described as apparently breaking one of the most basic safety limits in high energy astrophysics.

Stealing matter, shrinking orbits

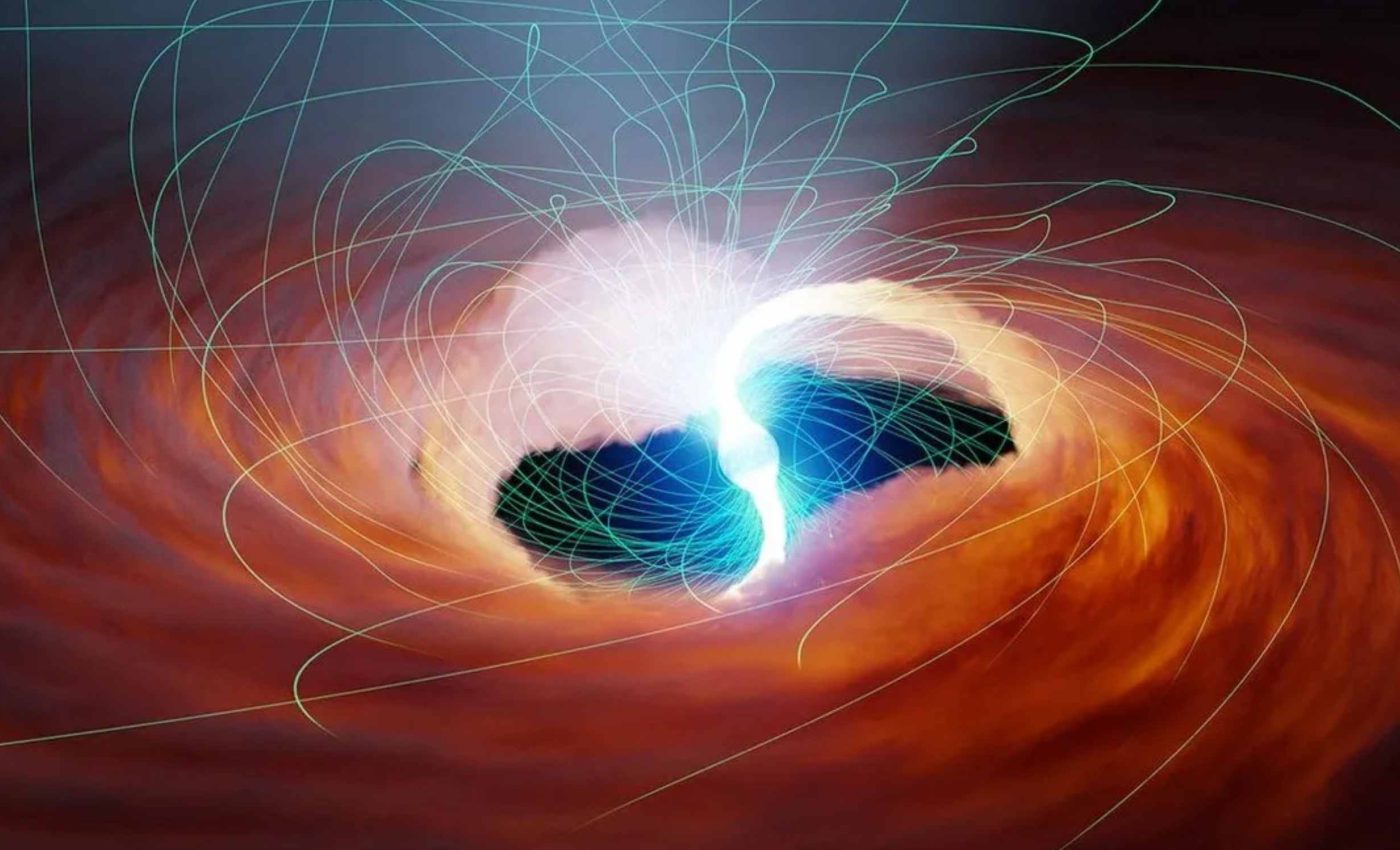

In this system, gas from the companion star flows into an accretion disk, a rotating disk of hot gas spiraling toward the neutron star. Friction and compression inside the disk heat the gas until it glows in X-rays before finally crashing down on the star’s surface.

A recent study followed about eight years of NuSTAR data and tracked small shifts in how long it takes the neutron star to complete an orbit, using tiny changes in the arrival times of its X-ray pulses.

Those timing measurements show that the orbital period is slowly shrinking, a classic sign that large amounts of mass and angular momentum are being transferred within the system.

From the rate of this mass transfer, gas flowing from one star to its companion, the team inferred that the neutron star is being fed at more than 150 times the Eddington mass accretion rate for an ordinary neutron star.

That level of inflow is enough to explain the observed light without needing extreme beaming tricks that would simply point the emission in our direction.

This slow orbital decay, a gradual shrinkage of the orbit over time, means that over millions of years the two stars will spiral ever closer together.

The donor star will keep losing mass, and the system will evolve toward a tighter, more compact pair that may eventually look very different from the ULX we see today.

Magnetic fields near M82 X-2

Close to the neutron star, the gas feels a fierce magnetic field, a region where magnetic forces strongly influence charged particles.

Estimates place the field strength above 10^13 gauss, far above typical neutron stars and close to what astronomers call magnetar territory.

Theoretical work shows that in such extreme fields the usual interaction between X-ray photons and electrons is altered, which lowers the effective scattering of radiation along the field lines.

Under those conditions, matter can ride down narrow funnels guided by the field and radiate far above the normal Eddington limit without being blown away.

The new timing results support that picture for M82 X-2, because the extreme mass transfer implied by the shrinking orbit matches the output expected from a highly magnetized neutron star fed at that rate.

Modeling also suggests that the inner edge of the disk sits near the point where magnetic forces and rotation balance, another clue that the magnetic field is doing much of the hard work.

“These observations let us see the effects of these incredibly strong magnetic fields that we could never reproduce on Earth with current technology,” said Bachetti.

Lessons from M82 X-2

For physicists, M82 X-2 acts as a natural laboratory where matter, light, and gravity meet under conditions far beyond any facility on Earth.

Each new observation helps test ideas about how radiation pressure, magnetic pressure, and gravity divide up the work of moving gas around a compact object.

Understanding how super bright neutron stars work also feeds into bigger questions about how close binary systems evolve and sometimes produce double neutron stars or black hole pairs.

Those systems can later merge and send out gravitational waves that detectors like LIGO and Virgo are built to record.

The new view of M82 X-2, powered by extreme mass transfer rather than by an oversized black hole, hints that many other ultraluminous X-ray sources might also hide neutron stars at their cores.

If that idea holds up, then strong magnetic fields and super Eddington accretion could explain a large share of the ULX population in the nearby universe.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–