NASA warns the Sun is 'waking up' again and could affect GPS, radio, and the power grid

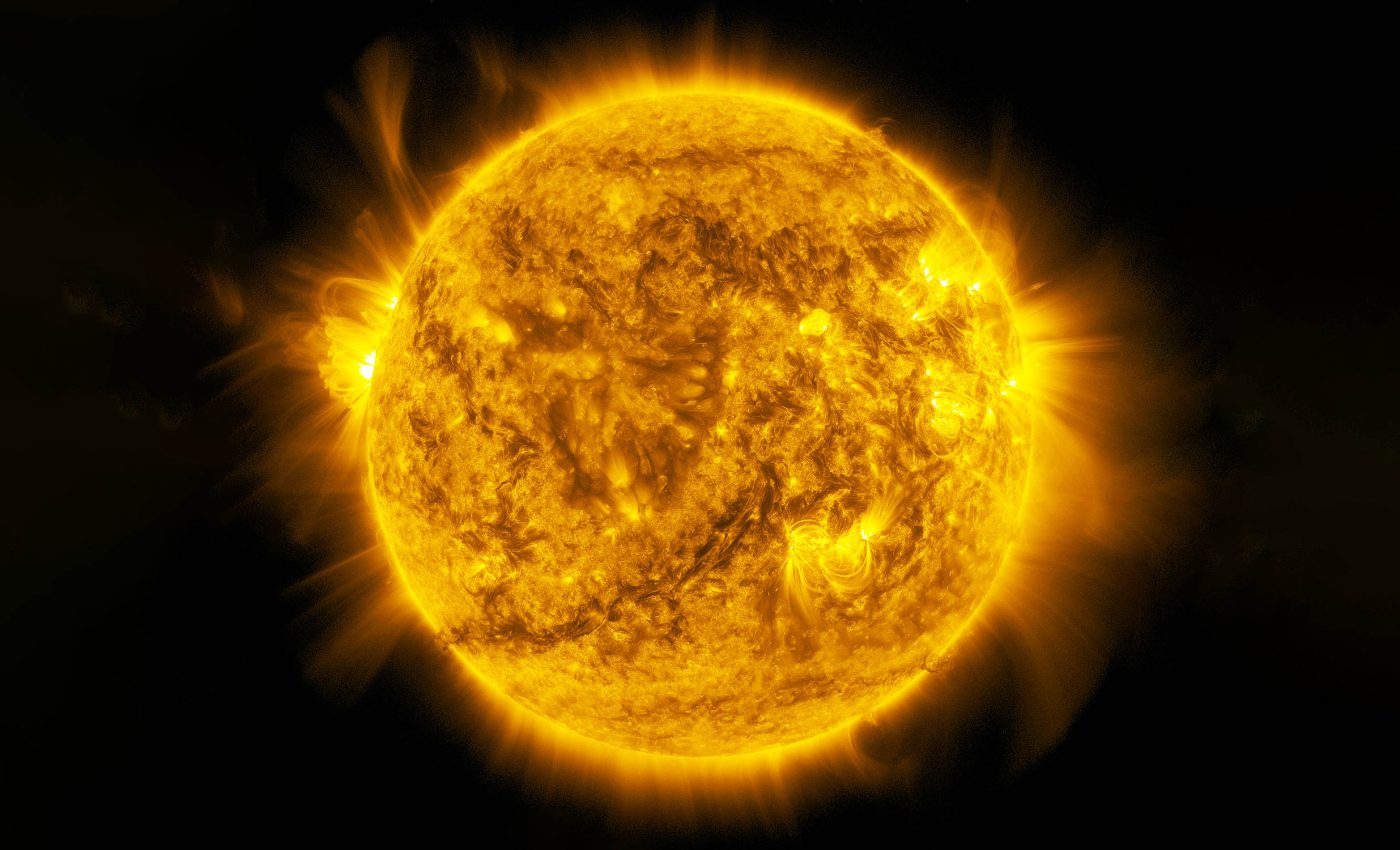

Imagine the Sun as a giant, boiling magnet that breathes in and out – slowly and rhythmically – every 11 years. That rhythm shows up in things we can count and measure.

These include things like the number of sunspots, the speed and density of the solar wind (a stream of charged particles constantly blowing off the Sun), and the strength of the Sun’s magnetic field.

For decades, it looked like the Sun was heading for a long nap. Since the 1980s, solar activity had been slowing down, and by 2008, it hit the quietest point in recorded history.

Scientists thought the Sun was slipping into a long period of low activity – maybe even one that would last for generations.

That’s not what happened. Instead, the Sun flipped the script. In a surprising twist, it started to get more active – not less.

A new study shows that solar activity has been rising steadily ever since, reversing what scientists thought was going to be a historic decline. And now, the Sun is waking up – slowly, but clearly.

Understanding solar cycles

The Sun doesn’t shine with the same intensity all the time – it follows an approximately 11-year solar cycle. During this cycle, the number of sunspots on the Sun’s surface rises and falls.

Sunspots are cooler, darker patches caused by intense magnetic activity. When there are lots of sunspots, the Sun is in its “solar maximum,” meaning it produces more solar flares and eruptions of charged particles.

At “solar minimum,” sunspots are few, and solar activity is relatively calm. These changes aren’t random – they come from the twisting and shifting of the Sun’s powerful magnetic fields.

But that’s just the short-term rhythm. There are also bigger, slower trends that stretch out over decades. These are harder to predict – and sometimes, they take strange turns.

Scientists study solar cycles to predict when these disturbances are likely to happen, which helps protect technology and infrastructure.

Understanding solar cycles also deepens our knowledge of how stars behave, since the Sun is our closest example of a star in action.

Big turnaround in the Sun’s activity

“All signs were pointing to the Sun going into a prolonged phase of low activity,” said Jamie Jasinski, lead author of the study and a space physicist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).

“So it was a surprise to see that trend reversed. The Sun is slowly waking up.”

Jasinski and his team analyzed data from multiple NASA spacecraft – some of which have been monitoring the Sun since the 1990s.

They pulled data from the ACE and Wind missions, among others, using NASA’s OMNIWeb Plus platform.

What they found was clear: after the sharp low point in 2008, both solar wind and magnetic field strength have been climbing.

This wasn’t what scientists were expecting.

In the years before 2008, sunspot numbers and solar wind both dropped so low that researchers assumed we were heading for another “deep minimum” – a quiet stretch like the one that lasted from 1790 to 1830.

Why sunspots matter

Sunspots are cooler, darker patches that show up on the Sun’s surface. They show up where the Sun’s magnetic fields are especially active.

When sunspots increase, the Sun tends to get more rowdy – throwing off solar flares and massive blasts of plasma called coronal mass ejections.

These outbursts, known as space weather, aren’t just something for scientists to watch through a telescope.

They can mess with GPS systems, knock out radio signals, disrupt power grids, and put satellites at risk.

For astronauts – especially with NASA pushing ahead on missions like Artemis – stronger solar activity also means higher exposure to radiation. That’s why scientists track the Sun so closely.

More activity means more solar storms. It also means that Earth’s magnetosphere – the protective magnetic bubble around our planet – has to work harder. The stronger the solar wind, the more pressure it puts on that shield.

The Sun’s next chapter

NASA’s upcoming missions – like IMAP, the Carruthers Geocorona Observatory, and NOAA’s SWFO-L1 – are set to launch in late September.

These spacecraft will study space weather in more detail and help scientists understand how to keep astronauts safe from solar radiation.

Understanding the Sun’s long-term behavior is still a challenge. The earliest sunspot records go back to the early 1600s, when astronomers like Galileo began documenting them.

The longest quiet period ever recorded was between 1645 and 1715. But why those low-activity periods happen – or end – is still a mystery.

“We don’t really know why the Sun went through a 40-year minimum starting in 1790,” said Jasinski. “The longer-term trends are a lot less predictable and are something we don’t completely understand yet.”

Earth, the Sun, and future activity

Science doesn’t only celebrate flashy new particles or never-before-seen images. Sometimes the big win is noticing that a slow trend – the kind that’s easy to miss if you aren’t patient – has changed direction.

The researchers treated the Sun like a patient with vital signs: heart rate, temperature, blood pressure. For a long time those vitals were drifting downward.

Then, starting in 2008, they began to rise. That simple observation, backed by careful measurements, resets expectations for the next decade or two.

That’s why this recent trend matters. It changes the story scientists thought they were watching unfold. Instead of slipping into a long quiet phase, the Sun is ramping up – and it’s bringing space weather with it.

It tells satellite operators, grid managers, and astronauts to plan for a livelier space environment. And it challenges solar physicists to explain why the patient perked up when most of us thought it was nodding off.

The full study was published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–