New pumpkin toadlet discovered in the mountains is the size of a pencil tip

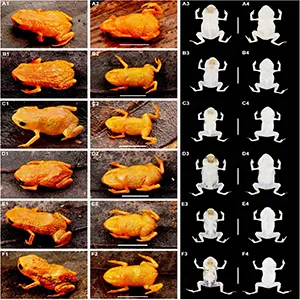

Researchers have recently described a new bright-orange pumpkin toadlet, Brachycephalus lulai, from Brazil’s Serra do Quiriri mountain forests.

Each adult is only about 0.4 inches long, with this tiny frog confined to a small patch of high forest in southern Brazil.

Meet the pumpkin toadlet survives

The genus Brachycephalus is miniaturized, meaning adults remain extremely small and their eggs develop straight into tiny froglets on land.

“The genus includes 42 currently recognized species, 35 of which, being described since 2000,” said Dr. Marcos Bornschein of Federal University of Paraná.

His research focuses on the evolution and conservation of these tiny Atlantic Forest frogs and other microendemic Brazilian amphibians.

Brachycephalus lulai has a rounded snout, smooth orange back, tiny green speckles along its sides, and females slightly longer than males.

The species is known only from Serra do Quiriri, and researchers categorize it as “Least Concern,” meaning no major threats are evident today.

Brachycephalus lulai‘s habitat

Serra do Quiriri is a rugged mountain range on the border between the Brazilian states of Paraná and Santa Catarina.

It lies inside the biodiversity hotspot, an area rich in species under pressure, where one fifth of the original forest still survives.

On these slopes, montane rainforest gives way to cloud forest, a high-elevation woodland that stays humid and misty most of the year.

Brachycephalus lulai spends its life hidden in the leaf litter of this damp forest floor, active during the day rather than at night.

Brachycephalus lulai characteristics

Most pumpkin toadlets show direct development, meaning eggs laid on land hatch as froglets rather than as free swimming tadpoles.

Many species are microendemic, restricted to one or a few mountaintops in the Atlantic Forest and especially vulnerable to local change.

Extreme miniaturization has trimmed their skeletons, leaving some species with missing toe bones, shrunken skulls, and highly compacted bodies over evolutionary time.

Many pumpkin toadlets are intensely colored in oranges and yellows, likely advertising potent skin toxins to predators that learn to avoid them.

Pumpkin toadlet bones

CT scans of Brachycephalus lulai reveal a short skull, fused vertebrae near the hips, and a mineralized layer just within the back skin.

Some relatives have bones that emit fluorescence, light released after absorbing wavelengths, which then shines through their skin under UV light.

In Brachycephalus lulai, histology shows a mineralized dermal layer covering much of the back, which may stiffen the skin and influence color.

Researchers still do not know whether these mineralized skin features mainly protect fragile bodies or instead support visual signals and communication.

High-frequency communication

Male Brachycephalus lulai call during the day in a slow series of isolated notes, sometimes switching to pairs of notes separated by pauses.

Many calls begin with very soft notes that fade in before the louder ones, a pattern the authors describe as attenuated notes.

Other pumpkin toadlets show auditory insensitivity, a loss of high-frequency hearing that prevents them from detecting their own calls.

Scientists suspect that in such species, bright colors and body movements may carry more information than sound in communication.

Living on islands in the sky

Biologists call these mountaintop forests sky islands, isolated high elevation habitats separated by warmer lowlands that act as barriers for ground-dwelling frogs.

Within Serra do Quiriri, Brachycephalus lulai lives with two close relatives on neighboring heights, each confined to a separate patch of forest.

Geological evidence suggests that during past dry periods, forests in this region retreated downslope, then expanded upslope as wetter conditions returned.

Researchers think these moving forest belts created small microrefugia, tiny stable patches where populations became isolated long enough to split into distinct species.

Protecting Brachycephalus lulai

Even though Brachycephalus lulai is not yet considered threatened, its known area of occupancy is only about 3 square miles.

The surrounding mountains already face grassland fires, cattle grazing, invasive pines, roads, and tourism trails that can damage forests if they expand upslope.

Across the Atlantic Forest, remaining fragments are often small and isolated, making species with tiny ranges especially exposed to any local disturbance.

The team proposes Refúgio de Vida Silvestre Serra do Quiriri, a conservation unit where forests and grasslands would remain mostly in private hands.

Tracking species recovery

Beyond the usual Red List categories, scientists use the Green Status to score how fully a species has recovered across its range.

Using that framework, the authors estimate Brachycephalus lulai is currently non-depleted, with populations functioning well across their tiny known slice of habitat.

Several of its close relatives in the same species group score as moderately or critically depleted, reflecting small ranges and habitat pressure.

A Wildlife Refuge on Serra do Quiriri could keep Brachycephalus lulai and Brachycephalus auroguttatus non-depleted, while helping Brachycephalus quiririensis approach recovery.

Lessons from Brachycephalus lulai

The species name honors Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, linking this tiny frog to national conversations about conserving Brazil’s remaining mountain forests.

However, naming a species after a political leader does not safeguard it, and lasting protection will depend on enforcement and local support.

By combining genetics, anatomy, and recordings of calls, the team shows how small vertebrates can diversify when landscapes fragment into tiny patches.

Brachycephalus lulai clarifies how life responds to changing climates, showing that protecting tiny habitats can preserve long evolutionary histories over time.

The study is published in PLOS One.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–