New soil carbon map shows where the US is losing the most CO2

Soils across the United States are not equal when it comes to how fast they leak carbon dioxide into the air. A new national analysis finds that soil organic carbon can break down more than tenfold faster in some samples than in others.

That imbalance makes these new results important for climate forecasts and for programs that pay landowners to keep carbon in the ground.

Why soil carbon matters

Organic matter in soil breaks down over time, sending some carbon into the air as carbon dioxide and leaving some stored underground.

The work was led by Chaoqun Lu, an associate professor at Iowa State University who studies how land ecosystems store and release carbon. Her research focuses on the processes that shape long term soil carbon change.

Soils worldwide hold more carbon than the atmosphere and all vegetation together, according to an analysis that combined measurements from many ecosystems.

Much of that long lasting carbon sits as mineral-associated organic carbon, carbon that sticks to fine particles and can stay in soil for decades.

Global Earth system models, tools that track exchanges of carbon, water, and energy between land, ocean, and air, still struggle with soil carbon.

One evaluation of the latest generation of these models found large errors in how much soil carbon they predict across the globe.

The new study tackles one missing piece, the basic tendency of different soils to release carbon once microbes begin working on organic matter.

Researchers call that tendency intrinsic decomposability, the base decay rate measured under the same temperature and moisture before outside stresses are added.

Studying soil carbon systems

Across the U.S., the team used the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), a nationwide facility that tracks ecosystems at field sites.

From that system they selected 20 locations, ranging from deserts to forests, and collected 156 soil samples for intensive lab work.

In the lab, each soil sample spent 18 months in controlled temperature and moisture. During that period, researchers tracked carbon dioxide coming off the soil and traits such as pH, nitrogen, and microbial activity.

Those measurements fed into a mechanistic soil model that estimated two key numbers for each sample, its decay rate and its carbon use efficiency.

Carbon use efficiency, the share of decomposed carbon microbes kept in bodies instead of exhaled as gas, shows how carbon stays in the soil.

The team then used machine learning to test which of 26 measured soil properties best explained differences in those decay rates and efficiencies.

Well known factors such as soil type, pH, and nitrogen remained important, but fungal abundance and certain iron and aluminum forms also stood out.

Minerals, microbes, and controls

Researchers have increasingly learned that interactions between organic matter and minerals often decide whether carbon stays in soil or escapes.

A recent review showed that iron and aluminum oxides form tight bonds with organic molecules, slowing their breakdown across many soil types.

In the new analysis, soils richer in those metals and fungi showed slower decay and higher carbon use efficiency in mineral associated carbon.

By contrast, soils where most carbon sat in loose particles with fewer protective minerals released a larger share as gas once microbes decomposed it.

Scientists refer to that loose pool as particulate organic carbon, relatively fresh plant material and fragments that typically decompose within a few years.

Because this fraction is more exposed to microbes and less bound to minerals, it often responds faster to warming or shifts in moisture.

For decades, many modeling studies have treated soils of the same type or biome as sharing one base decay rate when conditions stay constant.

Soil behavior across the U.S.

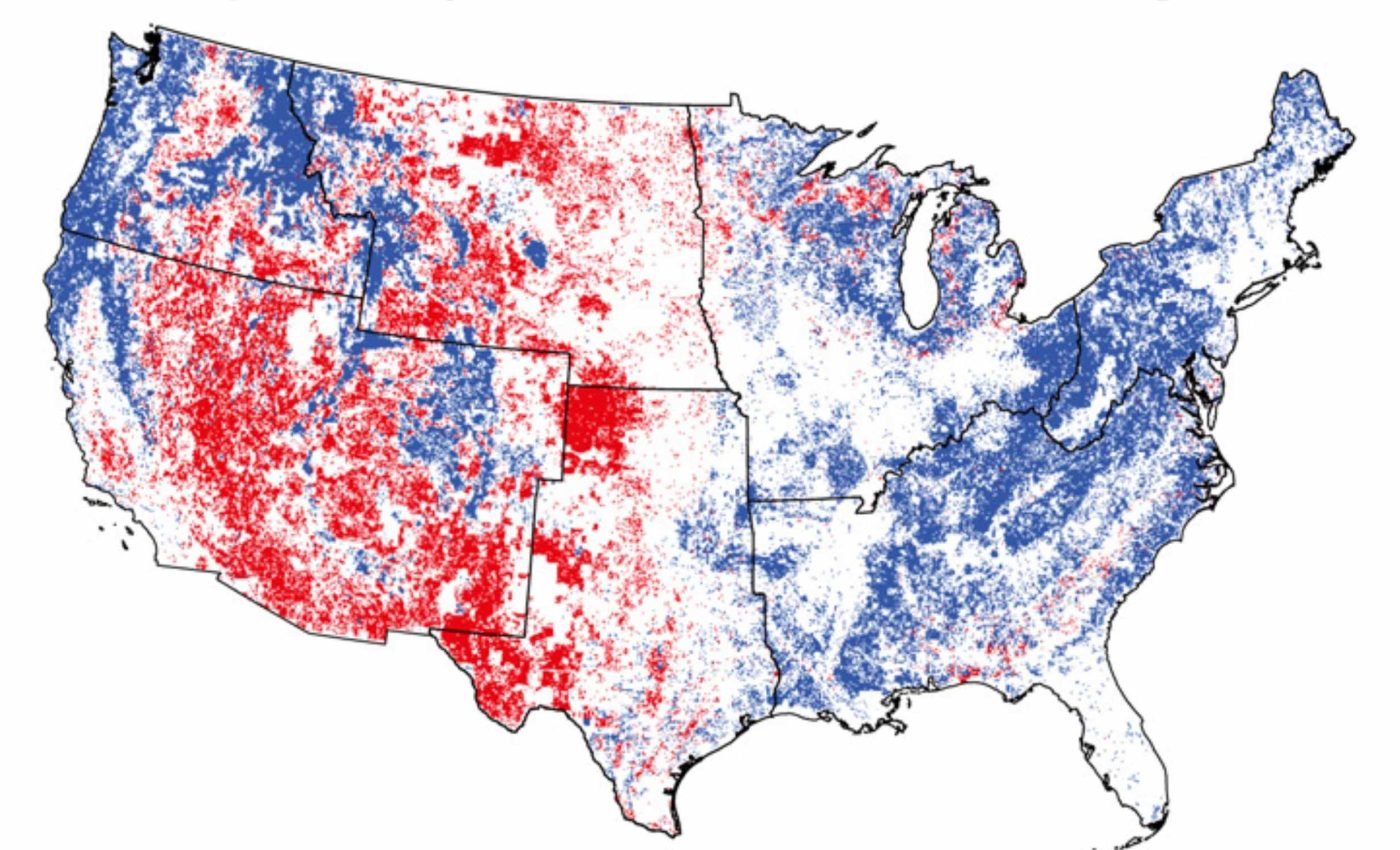

Using the fitted model, the team produced national maps that estimate decay rate and carbon use efficiency for both particulate and mineral-associated carbon.

Each mapped cell covers roughly a square 2.5 miles on a side, fine enough to capture differences between regions that share the same climate label.

The resulting maps show that soils in the Southwest break down carbon faster and send more of it into the air as carbon dioxide.

In the Northwest and much of the East, decomposition runs slowly and more carbon becomes microbial biomass, while the Midwest shows intermediate behavior.

That pattern highlights stable pockets of soil carbon in parts of the Northwest and eastern United States, where mineral-associated pools are abundant and decay rates stay low.

By contrast, regions with thinner protective mineral layers or disturbance may see soil carbon stocks shrink faster when climate warms or land use changes.

Lessons from soil carbon

Earth system simulations guide carbon budgets for countries and companies, and they also underpin many land based carbon offset projects.

If those simulations underestimate how fast some soils lose carbon or overestimate persistence elsewhere, climate plans built on them can be off the mark.

The researchers expect other modeling groups to start using their parameter maps as inputs to improve simulations of carbon climate feedback.

On the policy side, the regional differences in carbon retention suggest that carbon market rules may need to look beyond simple totals.

A member of the team explained that carbon held longer in certain regions may offer greater long term benefits than identical amounts stored elsewhere.

Land managers could use this mapping to decide where practices like cover crops and forest restoration will keep carbon in soil longer.

As similar studies extend to other continents, soils that once looked uniform in climate models start to show detailed patterns that can guide decisions.

The study is published in One Earth.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–