Prehistoric humans seem to have walked to Europe from Turkey on 'lost' land bridge

For a long time, scientists thought that early humans arrived in Europe primarily by traveling north into the Balkans or eastward from the Levant. However, a new find in the Ayvalık region of western Turkey suggests that prehistoric humans somehow “walked” across what is now a deep body of water.

A new collection of stone tools discovered in the Ayvalık area indicates another, yet unknown potential pathway: directly across a now-overwhelmed land bridge in the Aegean.

This area, now famous for olive groves and beautiful beaches, might have been a dry and traversable trail tens of thousands of years ago – and it may have been traversed by early humans long before history was ever recorded.

Humans on vanished Ayvalık land

During the last Ice Age, global sea levels dropped by over 300 feet (91 meters). Wide strips of land that are now hidden underwater were exposed at that time.

In particular, the islands and peninsulas of Ayvalık weren’t scattered bits of land – they were part of a solid landmass.

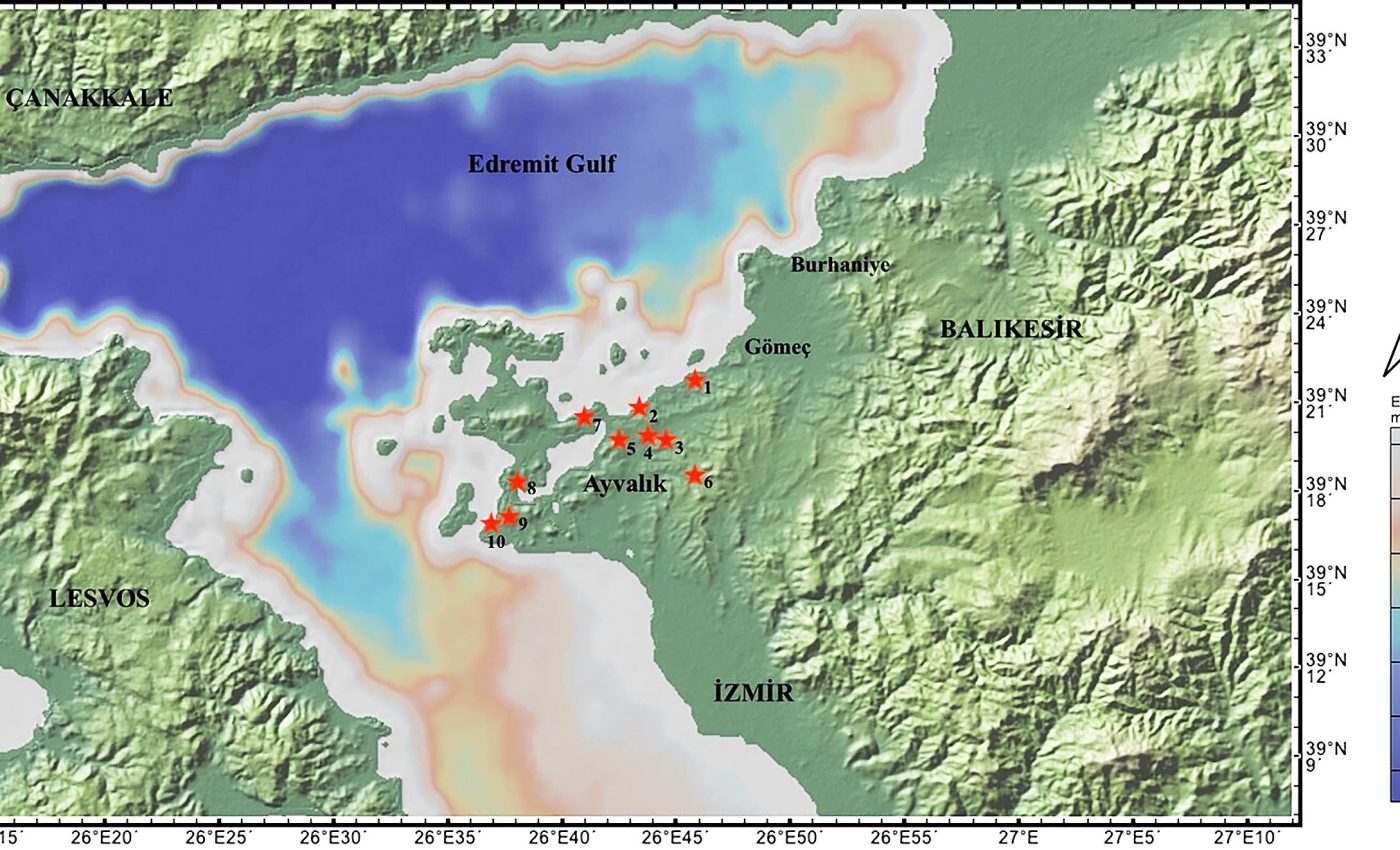

Archaeologists found 138 stone tools spread across 10 sites in a 77-square-mile (200-square- kilometer) area.

These artifacts point to a time when humans were making their way across this stretch of land, possibly heading into Europe.

The idea is simple: when the sea receded, it revealed a path, and early humans walked along it.

Unearthing a forgotten route

The discovery was led by a team of expert archaeologists in Turkey.

“Our archaeological discovery has unveiled that this now-idyllic region once potentially offered a vital land bridge for human movement during the Pleistocene era – when sea levels dropped and the now-submerged landscape was briefly exposed,” said Dr. Göknur Karahan from Hacettepe University.

“These findings mark Ayvalık as a potential new frontier in the story of human evolution, placing it firmly on the map of human prehistory – opening up a new possibility for how early humans may have entered Europe,” she added.

Human tools in ancient Ayvalık

The tools uncovered were not just random stones. They were crafted with intention and technique. Some of the most important tools belonged to what’s known as the Levallois tradition.

This method of shaping stone is advanced and is usually tied to Neanderthals and early modern humans.

“These large cutting tools are among the most iconic artefacts of the Paleolithic and are instantly recognizable even today, so are a very important find,” said Dr. Karahan.

She added that the presence of these objects in Ayvalık is particularly significant, as they provide direct evidence that the region was part of wider technological traditions that were shared across Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Other finds included handaxes and cleavers – classic Paleolithic tools used for chopping and scraping.

Together, they show that early humans weren’t just passing through the area. They lived, worked, and possibly even stayed there for long stretches.

Reading the land

One of the challenges in Ayvalık is its ever-changing terrain. The area has active coastlines and shifting sediment, which makes it hard to preserve artifacts. Until now, this had made it almost impossible to confirm any ancient human presence.

“In all these periods, the present-day islands and peninsulas of Ayvalık would have formed interior zones within an expansive terrestrial environment,” explained Professor Kadriye Özçelik from Ankara University.

“These paleogeographic reconstructions underscore the importance of the region for understanding hominin dispersals across the northeastern Aegean during the Pleistocene.”

Despite the muddy, uneven ground, the team found a good number of tools made from strong materials like flint and chalcedony.

These materials survived even under difficult conditions, giving scientists the chance to study how they were used and what they might say about the people who made them.

Two weeks, one big find

The discovery didn’t come from a full excavation. It came from a short survey – just two weeks long – in June 2022.

The team didn’t know what they’d find, or if they’d find anything at all. They walked, scanned, and hoped.

“It was a truly unforgettable moment for us. Holding the first tools in our hands was both emotional and inspiring,” said Dr. Karahan. “And each find from there on was a moment of excitement for the whole team.”

What Ayvalık means for human history

Ayvalık is now on the radar as a possible key site in human migration. It could show that early humans weren’t just limited to one or two routes into Europe. They may have explored and adapted to whatever paths the environment opened up.

“The findings paint a vivid picture of early human adaptation, innovation, and mobility along the Aegean,” said Dr. Karahan.

“The results confirmed that Ayvalık – which had never before been studied for its Paleolithic potential – holds vital traces of early human activity.”

This discovery also opens up new questions. If Ayvalık was once a busy route, what else lies beneath the water and mud? What other tools or even bones are hidden, waiting to be found?

More clues about early humans

“Ultimately the results underline Ayvalık’s potential as a long-term hominin habitat and a key area for understanding Paleolithic technological features in the eastern Aegean,” said Dr. Hande Bulut from Düzce University.

She believes that more work is needed – especially studies that include dating methods, deep excavation, and environmental analysis.

That’s how researchers can learn exactly when people lived there and how they used the land.

“Excitingly, the region between the North Aegean and the Anatolian mainland, may still hold valuable clues to early occupation, despite the challenges posed by active geomorphological processes,” she said.

This might be just the beginning.

The full study was published in the journal Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–