Two prehistoric sea monsters found after 325 million years in the world’s largest cave

Mammoth Cave in Kentucky stretches for more than 420 miles (675 kilometers) below the surface of the ground and is often described as the world’s largest cave system. Recent explorations there uncovered two new fossil sharks that once roamed shallow coastal waters more than 325 million years ago.

Ancient shark specialist John-Paul (JP) Hodnett of the Maryland-National Capital Parks and Planning Commission (MNCPPC) worked with the National Park Service Paleontology Program to identify the fossils.

These finds have everyone buzzing because they offer a glimpse into marine habitats that thrived when parts of what is now eastern North America were covered by a warm sea.

Prehistoric shark fossil puzzle

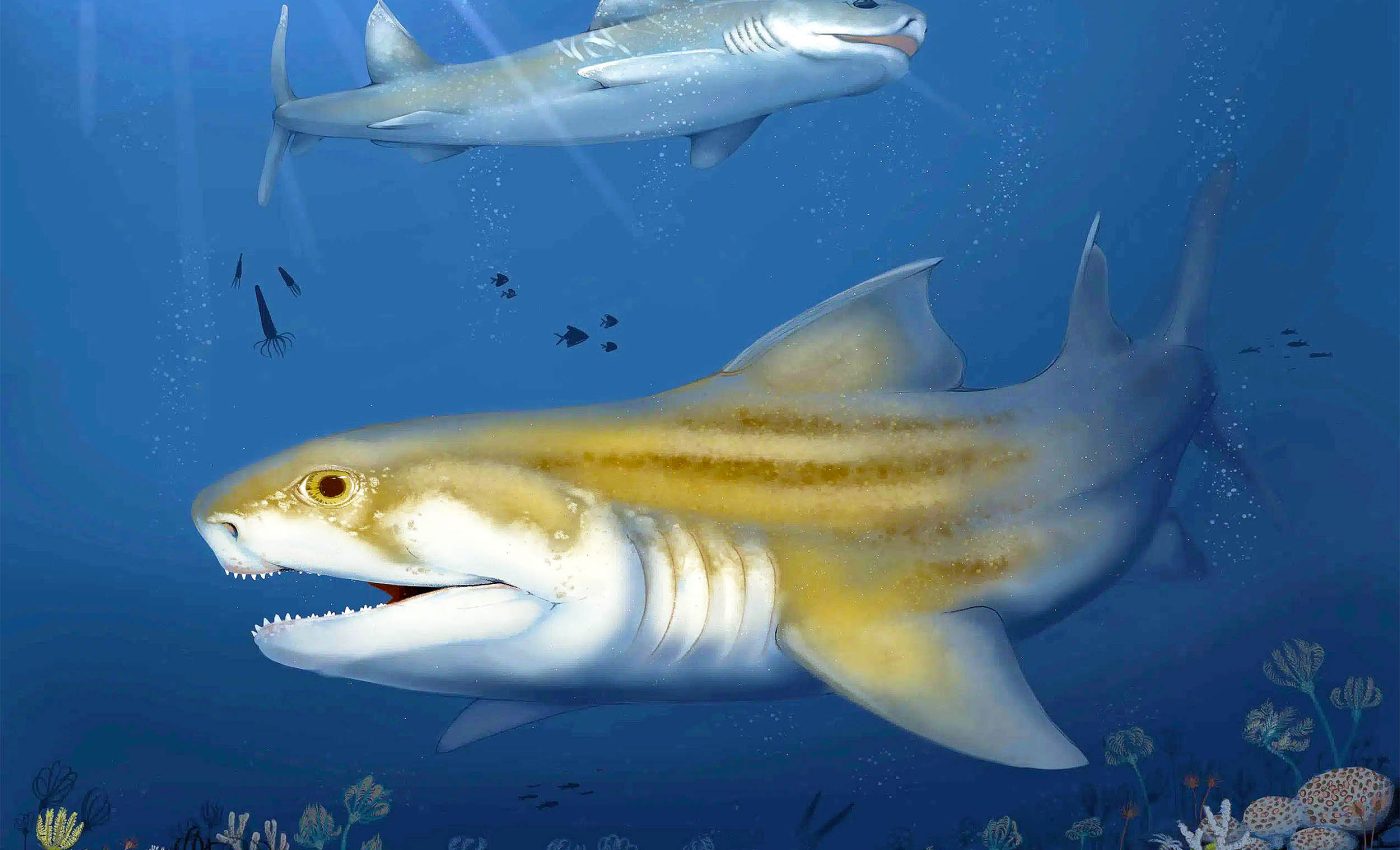

The newly documented sharks are Troglocladodus trimblei and Glikmanius careforum, and they are from a group known as ctenacanth sharks.

They both measured about 10–12 feet (3–3.6 meters) long, which is similar in size to an oceanic whitetip shark.

The shark fossils were collected from various limestone formations, which were deposited during the Middle to Late Mississippian Period.

The bigger picture is that these habitats were once submerged under shallow seas and supported a wide range of fish life. Researchers have now identified more than 70 ancient fish species in the cave system.

A partial set of jaws belonging to a young Glikmanius careforum revealed fresh details about cartilage, which rarely fossilizes well.

Cartilaginous remains of sharks are often fragile and easily destroyed by erosion, so finding them preserved in a protected space is especially rewarding.

Experts note that this newly identified material adds depth to ongoing discussions of how shark groups diversified while the supercontinent Pangea was taking shape.

Collaborations and fieldwork

“Every new discovery at Mammoth Cave is possible due to collaborations,” said park superintendent Barclay Trimble of Mammoth Cave National Park.

Researchers and volunteers have explored hidden passages, river channels, and even narrow crawlways in search of key fossils.

Members of the Cave Research Foundation also took part in these efforts. The name Glikmanius careforum was chosen to honor that organization’s valuable support in the field.

The partial cartilage from this genus points to a short head with a strong bite, possibly used to feed on smaller fish and orthocones, which are squid-like creatures with elongated shells.

Fossils help trace evolutionary change

Troglocladodus trimblei stands out for its branching tooth design that helped it secure prey in the Mississippian seas.

This prehistoric hunter probably shared a coastal environment with G. careforum, in waters that covered modern-day Kentucky and Alabama.

Researchers say these sharks likely thrived in nearshore habitats that teemed with bony fish, shelled organisms, and other marine creatures.

Tracing these fossils across multiple rock layers provides insights into how the environment changed over time.

Coastal waters rose and fell as landmasses drifted toward each other, gradually merging into a single continent.

These broader patterns helped shape the distribution and evolutionary paths of ancient sharks like T. trimblei and G. careforum.

How to preserve shark fossils

Field teams spent long hours underground carefully mapping and collecting small fragments of teeth. A single tooth from T. trimblei sparked initial interest when Superintendent Trimble first discovered it on a 2019 trip.

Seasoned cavers and geologists coordinated to ensure safe retrieval of each piece, knowing that one misstep could damage the delicate remains.

Research at Mammoth Cave has led to conversations about how best to preserve fragile fossils within difficult-to-access passages. Experts say stable cave temperatures help keep these discoveries in good condition.

Park managers have also integrated these new data into guidelines for future research so that more clues to marine life from 325 million years ago may be found.

Why these shark fossils matter

Scientists use these finds to compare local fossil collections with specimens from similar periods in other parts of the world.

Documenting body sizes, tooth arrangements, and skeletal details helps researchers build a clearer timeline of shark evolution.

These comprehensive studies uncover shifts in fish diversity that occurred as oceans changed and landmasses joined together.

Experts also link fossil data with knowledge from bony fish records, coral structures, and other sea life. This combined approach paints a full picture of ancient marine habitats and shows how some species adapted while others vanished.

The two new fossil sharks at Mammoth Cave highlight that even well-known geologic areas can hold surprises for many years.

Future cave explorations

Mammoth Cave continues to yield glimpses into a vanished coastline that spanned what is now Kentucky, Europe, and northern Africa.

T. trimblei and G. careforum are just two recent additions to an ever-expanding fossil catalog, reminding everyone that exploration still brings answers and new questions.

In many ways, these ancient sharks highlight how puzzle pieces of geologic history keep fitting together. Field teams are now eager to see what lies in deeper chambers or behind the narrow channels.

The next phase of study may involve more advanced imaging and careful excavation in lesser-known passages, guided by new mapping techniques.

Findings like these spur a broader appreciation for the cave system’s scientific value, well beyond its length or visual features.

The study is published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–