Protections for the pangolin may threaten an already endangered fish

Pangolins are the most illegally trafficked animals in the world today. A scaly anteater group comprised of eight species living in Africa and Asia, the pangolin relies on its scaled body armor for protection, leaving them an easy target of poachers.

The Center for Biological Diversity reports that approximately one million pangolins were poached from the wild over the last decade. Some pangolins have seen a 50% reduction rate in their populations. This devastating decline lead to an international rule of zero exports of Asian pangolins in 2000, as well as the US Fish and Wildlife Service starting investigation into additional protections for pangolins in 2015.

Most of the attention given to the plight of the pangolin puts the blame for the pangolin’s demise on traditional Chinese medicine. But China is not the only country with a demand for pangolin products though, as the US imports pangolin skins for a different reason. Exotic looking boots have been made from pangolin skin, something most consumers are probably unaware of.

Being the only scaled mammal in the world means that pangolin skin has a unique diamond pattern that most people would probably associate with a reptile skin, not that of a mammal. The pattern unfortunately seems to be attractive to many cowboy boot makers and those who purchase the boots. The scales that create the diamond pattern in the leather are also what is most prized by traditional Chinese medicine as an ingredient in ineffective folk remedies. The unique skin is also used to make decorative leather items such as wallets and belts.

Although there is still a small scale amount of pangolin leather imported into the US, pangolin imports have dropped off dramatically since 2000, Smithsonian reports. Unfortunately, a substitute for the uniquely patterned skin was quickly found and may soon be as threatened as the pangolin.

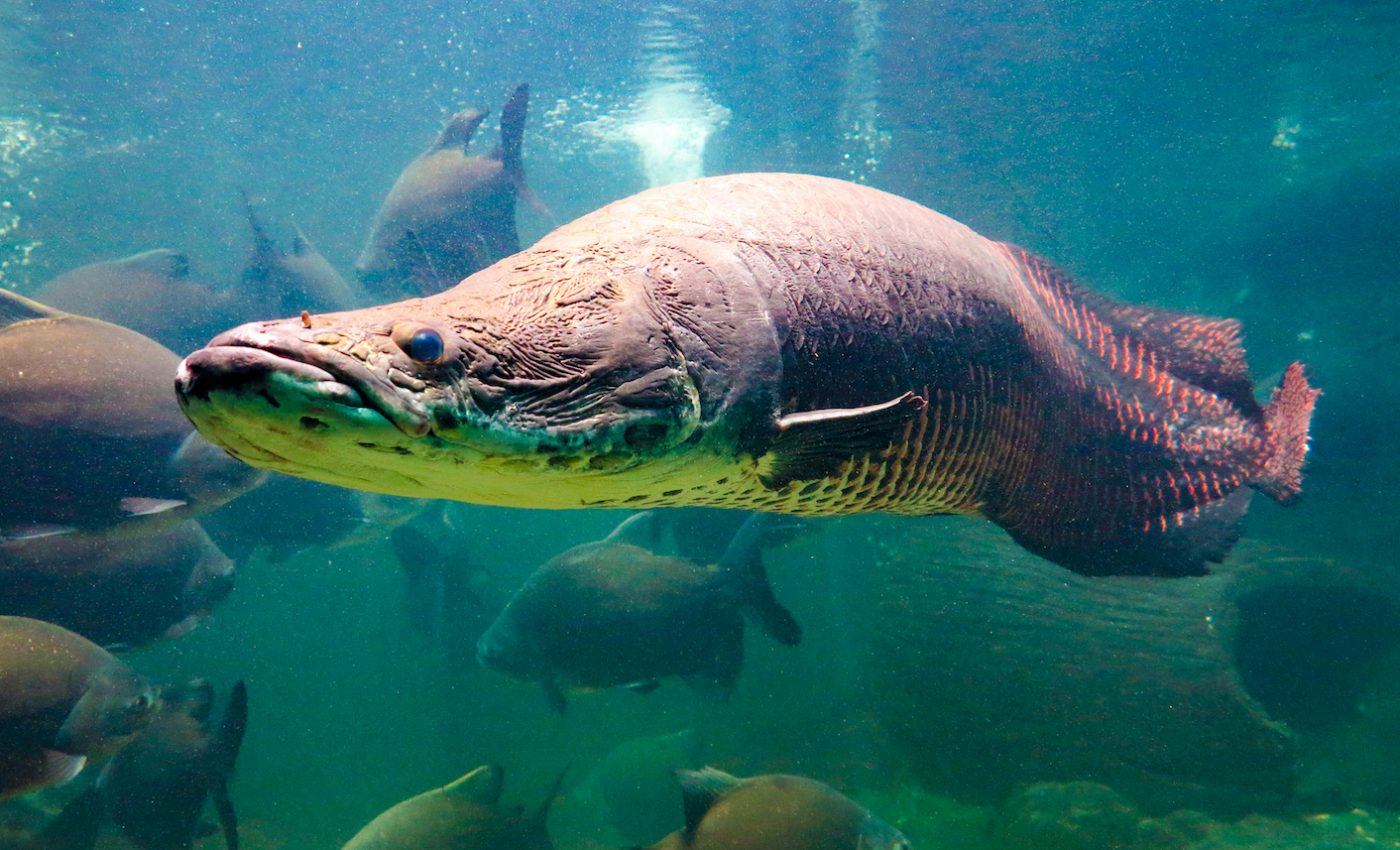

The arapaima is a genus of large, tropical South American freshwater fish. Arapaimas sometimes grow to 6 feet long and up to 400 pounds. The large fish looks very much like a giant betta fish but with slightly less flashy colors and very large, obvious scales. The most well-known arapaima species lives in the Amazon River basin and can grow to over nine feet long. Smithsonian’s National Zoo reports that the arapaima sometimes venture into oxygen starved waters where most fish cannot live, in the flooded Amazon forest, which it accomplishes by breathing air at the surface with a primitive lung.

The arapaima is also adaptable in its diet eating other fish but also insects, birds fruits and other plant material when these are available. The arapaima can also live up to twenty years. Unfortunately, the little scientific data on populations of the arapaima isn’t encouraging. NBC News reports that 3 of the 5 species of arapaima haven’t been observed in the wild for decades. Other species of arapaima simply lack in any official data to determine their conservation status at all.

Unfortunately for the arapaima, its interesting adaptation of breathing air from the surface also makes it an easy target for fishing. Arapaimas have to come to the surface of the water every 10 to 20 minutes to gulp in some air. A fish inhaling at the surface of dark water is easily speared or shot with an arrow. Of course, a four hundred pound fish is a lot of food but its skin is also used as boot leather.

The scaly skin of the arapaima is a nearly perfect substitute for that of the pangolin. Both skins when prepared show a similar diamond pattern on the leather. Smithsonian reports that due to greater international protections, pangolin imports into the US have fallen since 2000. Inversely, arapaima imports have risen since 2011, in many cases replacing pangolin skin in cowboy boots. A report from the University of Adelaide details the contribution of cowboy boots to the decline of both the pangolin and the arapaima. Sadly, the arapaima was already endangered due to overfishing before trade in its skin took off. In a bizarre twist, conservation of pangolins is actually pushing the arapaima closer to extinction. Of course, more attention has been given towards the cute pangolin than the monstrously sized arapaima.

So far, research is needed to determine the full impact of the exotic leather trade on the arapaima. We can only by common sense say that there must be some impact. Mongabay calls the arapaima a ‘forgotten species’ when compared to pandas, whales and other high profile endangered animals. The fish has long been a food source for Amazonian natives. But the demands of the modern era have increased fishing pressures in the Amazon as well as all over the world, including pressure on the arapaima.

Overfishing has shown large declines. Areas that initiated fishing bans on arapaima have shown dramatic increases in fish populations showing that there is some hope in regulated fishing. Unfortunately, data and general public interest are not abundantly present for the arapaima. The Amazon River is incredibly diverse in fish and other species but many have yet to be documented by science. It’s unclear what other species the arapaima may depend on for its survival or which depend on the big fish for theirs. Likewise, little is known about the habitat needs for feeding or mating or simply surviving for the arapaima.

The danger of the arapaima simply reflects the danger of a global system of consumption where someone in the US can wear a pair of shoes being unaware whether the leather they’re made from comes from a mammal or a fish. We live in an increasingly complex society where it is becoming harder to know the origin of any one product much less be self sufficient. This incredible ignorance and insatiable appetite is part of the interconnectedness of our ‘global society’, pangolins and arapaima alike fall prey to this system, something no animal has evolved to face. The question is, can we reshape that system and rethink the products we consume?

—

By Zach Fitzner, Earth.com Contributing Writer

Main Image Credit: Shutterstock/SergioRocha