Scientists are racing to name ocean species before they vanish

Millions of species – many still unnamed – fill our oceans with life. But there’s a tragic twist: countless species are vanishing before we even know they exist.

Some disappear forever without anyone studying, photographing, or understanding the role they played in Earth’s intricate web of life.

One reason for this is that it takes too long to describe and officially document new species. The process between a scientist spotting something new and the world hearing about it can drag out for decades.

That kind of delay doesn’t work when climate change, deep-sea mining, pollution, and overfishing are speeding up extinctions.

That’s where a new effort called The Ocean Species Discoveries project steps in – aiming to fix the problem by changing how scientists describe and publish new species.

Reinventing how species are named

Ocean Species Discoveries isn’t just a journal – it’s part of a larger push to speed up and clean up the process of identifying new marine invertebrates like worms, mollusks, and crustaceans.

The project was launched by the Senckenberg Ocean Species Alliance (SOSA). The platform cuts through years of academic red tape to deliver speed and clarity.

Species descriptions are concise, data-rich, and high-quality. The goal is to move quickly while keeping the science rigorous – and it’s already working.

In their second major collection of research, more than 20 scientists collaborated to describe 14 new species and two entirely new genera. These include fascinating life, ranging from tidal zones to over four miles beneath the ocean surface.

Technology meets the tide

Much of the progress came from a place called the Discovery Laboratory, built at the Senckenberg Research Institute. This isn’t your typical lab bench setup.

The lab gives scientists access to high-powered tools like light and electron microscopes, confocal imaging, molecular barcoding, and 3D scanning using micro-CT. These tools let scientists see and study marine animals without destroying the specimens.

It’s not just about saving time – it’s about preserving these creatures for others to study in the future.

“Our shared vision is making taxonomy faster, more efficient, more accessible and more visible,” the team wrote in their paper.

New species from the deep ocean

The animals in this study came from places as shallow as four feet deep to as far down as 21,200 feet. That’s deeper than most submarines go.

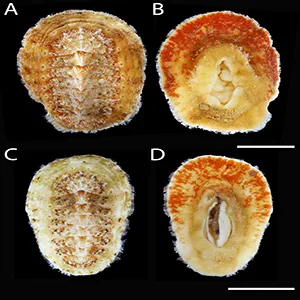

One of the deepest species described is Veleropilina gretchenae, a new kind of mollusk collected from the Aleutian Trench at 21,210 feet. This species is among the first in its class to have a high-quality genome mapped directly from the original specimen.

Another major find is Myonera aleutiana, a carnivorous bivalve. Scientists found this species between 16,960 and 17,320 feet down, setting a new depth record for its group.

Even more impressive, it was studied entirely using non-invasive 3D micro-CT scans – no dissection required.

The scan produced more than 2,000 high-resolution images, revealing its soft tissues and organs in striking detail. This marks the first time any Myonera species has been described using this technique.

Names that carry meaning

Researchers named one of the new species after Johanna Rebecca Senckenberg, who supported science and medicine in the 1700s.

Her name now lives on in Apotectonia senckenbergae, a tiny amphipod discovered at a hydrothermal vent in the Galápagos Rift at a depth of 8,537 feet (2,602 meters).

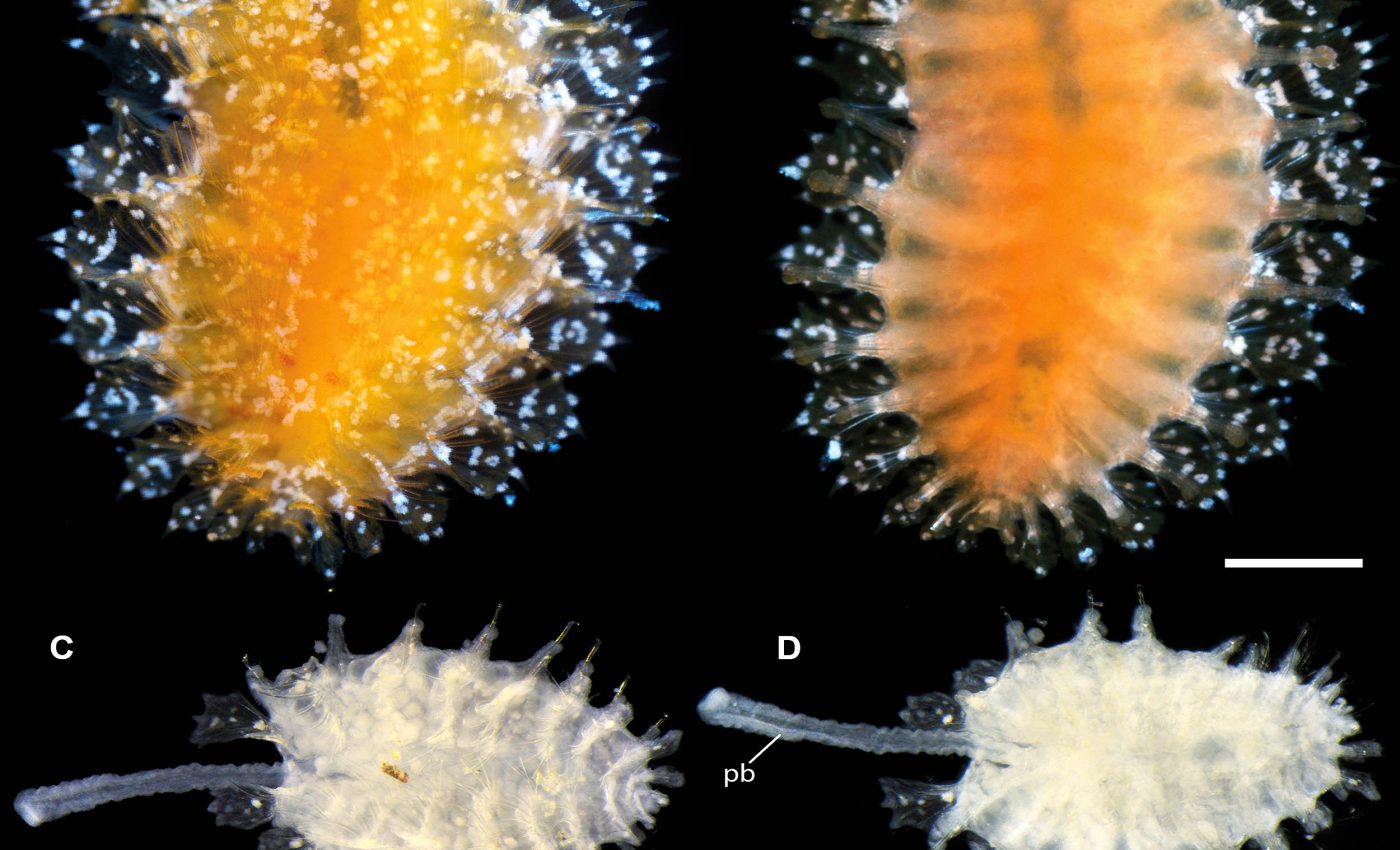

Some discoveries also brought a bit of humor. A parasitic isopod named Zeaione everta looks like it has popcorn stuck to its back – literally.

The name Zeaione derives from Zea, the genus name for corn, referencing the strange little lumps on the female’s body. Researchers found this species in Australia’s intertidal zone and identified it as a new genus.

The paper also describes a deep-sea tusk shell called Laevidentalium wiesei. Scientists noticed something odd: a sea anemone was stuck to the concave side of its shell. This is the first time this kind of interaction has ever been seen in that group of shellfish.

Racing extinction itself

All this work matters because the ocean is changing fast. When species vanish before scientists describe them, we lose not just a name but a puzzle piece in life’s story.

Each species might carry clues about evolution, medicine, or ecosystems. When a species vanishes without a trace, so does that knowledge.

Researchers recognize the urgency and are racing to name these mysterious species before they disappear for good.

The full study was published in the journal Biodiversity Data Journal.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–