Scientists drill 0.6 miles deep and find rocks that act as natural power plants

By drilling over half a mile into uplifted mantle rock beneath the Atlantic, scientists have recovered one of the most complete windows into Earth’s hidden interior ever obtained.

These altered, hydrogen-producing rocks behave like natural reactors. They offer clues to how deep-ocean chemistry works today and to how early life may have first powered itself billions of years ago.

Mantle rock raised upward

Earth’s mantle, a deep rocky layer beneath the crust, makes up most of the planet’s volume. Normally, it lies many miles below our feet, but at the Atlantis Massif tectonic forces have pushed mantle rocks upward toward the ocean floor.

At this site the drill cut deep below the seafloor, recovering a nearly continuous column of dense greenish rock.

A recent study, led by Professor Johan Lissenberg, a geologist at Cardiff University, examined this core from Atlantis Massif. The team found that it captures mantle rock that has been strongly altered by seawater.

In describing the new core, the team emphasized its value for revealing deep processes preserved in the rock. They also noted that the samples could offer important insights into the planet’s makeup and evolution.

Hydrogen from mantle reactions

These mantle rocks contain a dark mineral called olivine, rich in iron and magnesium. When seawater seeps into cracks and reacts with olivine, it triggers serpentinization. This chemical process changes the minerals and releases hydrogen gas.

That reaction also makes the fluids very reducing, meaning they carry electrons that living cells or simple organic molecules can use as energy.

Work has shown that when seawater reacts with ultramafic rocks, iron-rich minerals shift into new forms and release hydrogen gas.

This hydrogen-rich environment can sustain microbes that do not rely on sunlight, using chemical reactions instead of photosynthesis to live.

Steady hydrogen matters

Because the reaction depends on water slowly moving through hot rock, it can produce hydrogen steadily for long stretches of geologic time.

Geologists are increasingly interested in natural hydrogen – hydrogen gas generated underground by rocks rather than by industrial plants.

The Atlantis Massif core lets scientists see exactly where that gas forms and how the rocks controlling it are layered.

Rocks reveal mantle makeup

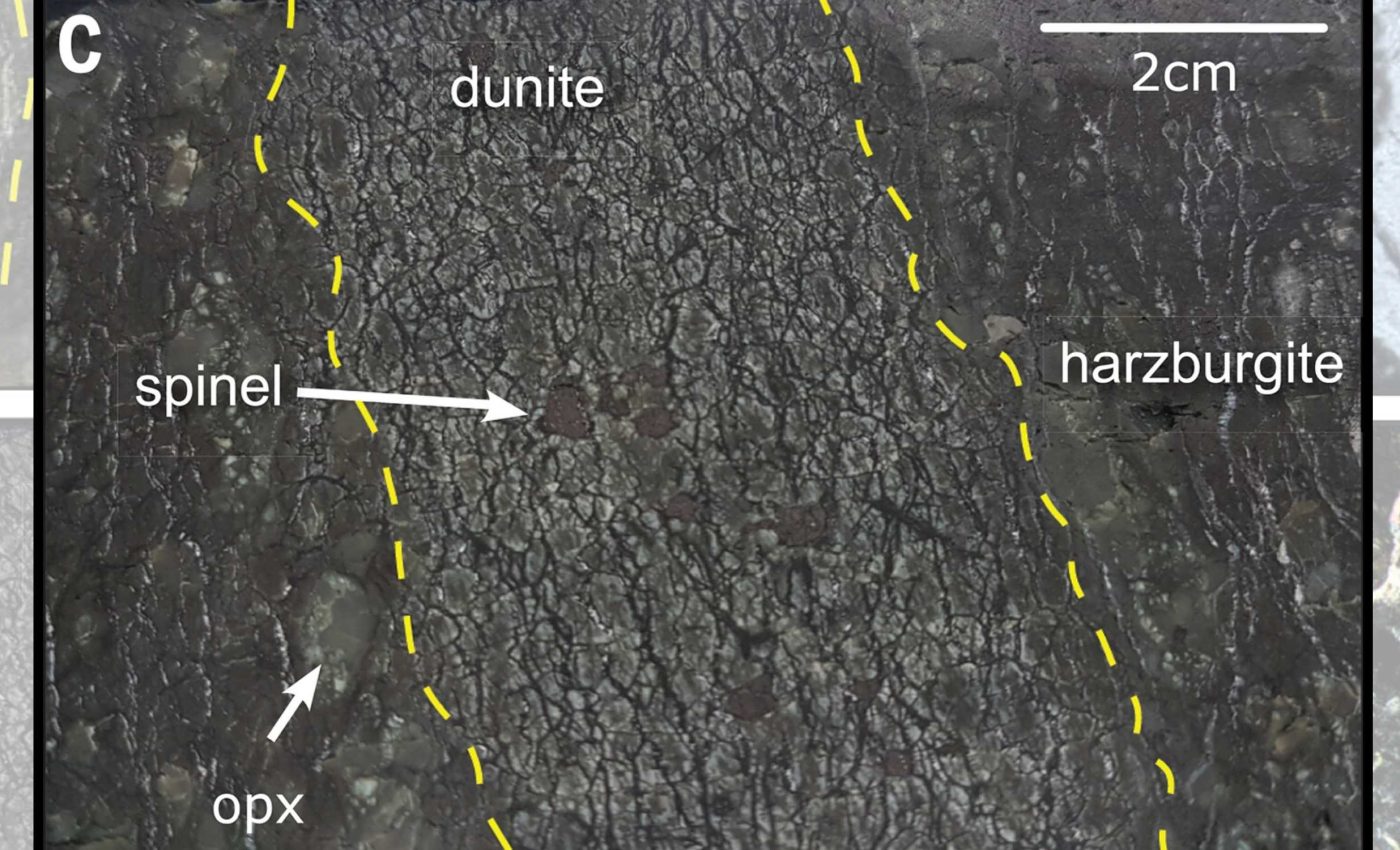

Most of the core is made of peridotite, a dense, dark rock that forms much of Earth’s upper mantle. Compared with typical mantle samples, these rocks hold far less of a mineral family called pyroxenes and more magnesium-rich material.

The combination tells geologists that the mantle under this part of the ridge has lost much of its melt, leaving it unusually depleted.

The core also shows channels made mostly of olivine-rich dunite and thin veins of frozen magma that cut through the rock.

Heat and fluids reshaping rock

By comparing channel directions with the fabric of the rock, the team found that melt once flowed along slanting paths instead of straight up.

That pattern suggests focused streams of melt feeding the ridge axis, leaving surrounding mantle rock even more depleted in melt-friendly elements.

Near the bottom of the hole, thicker bands of gabbro, a lighter colored frozen magma, appear between sections of peridotite.

These intrusions likely supplied heat and calcium-rich fluids that helped carve fluid pathways and form later carbonate veins higher in the rock column.

Hydrogen-rich vents

Just south of the drill site lies the Lost City field, a cluster of hot springs on the Atlantic seafloor. Each feature is a hydrothermal vent.

It is a seafloor spring where heated, mineral-rich water pours out of the crust and builds towering chimneys.

One study showed that tall Lost City towers vent hydrogen-rich fluids that support thriving microbial communities on the seafloor.

Those fluids come from seawater circulating through peridotite beneath the vents, reacting in ways very similar to what is happening inside the new core. The drill hole sits half a mile north of Lost City within the same block of uplifted mantle rock.

A recent paper mentioned hydrogen-rich fluids leaking from many points on the Atlantis Massif, not only at Lost City.

For the scientists on Expedition 399, that connection between deep rock and hydrogen-rich fluids is also a way to look back in time.

The team noted that the rocks from this site showed a closer resemblance to the material recovered during the expedition.

Early life’s chemical cradle

Many origin-of-life models now treat hydrogen-rich, alkaline environments like Lost City as promising birthplaces for the first metabolic networks.

Research has pointed to serpentinization as an increasingly likely source of the energy needed for early metabolic reactions.

Another review has highlighted alkaline hydrothermal vents as reactors that can persist for very long periods on the ocean floor.

Together with the new core, that picture suggests deep hydrogen-producing rocks and overlying vents can create stable niches for early life.

Mantle rocks and hydrogen

Looking ahead, mantle sections like this could guide the search for new natural hydrogen sources on land. Similar rock types reach the surface in many regions, making them potential targets.

They also help researchers estimate how hydrogen and other gases from such rocks influenced Earth’s history, climate, and chemistry.

The team plans years of lab work on these cores, from microbe hunting to mineral and fluid analyses. As results accumulate, this single Atlantic seafloor hole may become a key guide to how Earth’s engine and its hydrogen-rich rocks support life.

The study is published in Science.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–