Scientists have a plan to capture carbon by tapping the ocean's power

The ocean is already feeling the strain of a planet that cannot manage its carbon emissions. Earth is heating up faster than countries expected when they agreed in Paris to limit warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.

That target isn’t just a figure in a report. It marks the point where serious trouble grows into even stronger heat waves, rising seas, and widespread ecosystem loss.

At COP30 in Brazil, UN Secretary-General António Guterres did not sugarcoat it. “Science now tells us that a temporary overshoot beyond the 1.5°C limit – starting at the latest in the early 2030s – is inevitable,” he stated in his opening address.

“Let us be clear: the 1.5°C limit is a red line for humanity. It must be kept within reach. And scientists also tell us that this is still possible,” said Guterres.

Using the ocean to remove carbon

As pressure grows to keep that line “within reach,” attention has turned to the ocean – which already soaks up a huge amount of heat and carbon dioxide.

Some groups want to use the ocean more aggressively to draw carbon from the atmosphere. But a panel of experts with the European Marine Board warns that this rush is outpacing the safeguards needed to ensure it’s done responsibly.

The board is chaired by Helene Muri, an expert at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU).

The researchers set out to investigate whether carbon removal projects actually work and whether they damage ocean life.

“This is about safeguarding the oceans for a common good. The oceans can be part of the climate solution, but we need to strengthen the way we safeguard them before we scale things up,” said Muri.

Ocean carbon report at COP30

The group’s report, titled “Monitoring, Reporting and Verification for Marine Carbon Dioxide Removal,” was released alongside the COP30 talks.

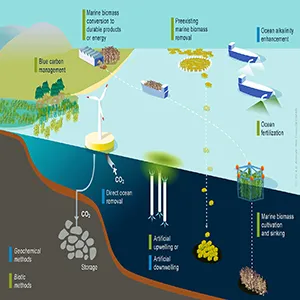

The researchers closely examined technologies that use the sea to remove carbon dioxide. These methods build on the ocean’s natural ability to absorb carbon.

Some are biological, such as boosting the growth of plankton or seaweed that take in carbon dioxide as they grow. Others are chemical or physical, including machines that strip carbon dioxide straight from seawater.

The captured carbon might then be stored on the seafloor, buried in sediments, pushed into the deep ocean, or locked into geological reservoirs and long-lasting products.

Cutting emissions still comes first

Even as interest in carbon removal grows, the report puts one message right at the top. Emissions cuts come first.

“We know how to cut emissions, and we have lots of methods that work,” Muri said. “That has to take top priority.”

Many tools for cutting carbon emissions already exist, from renewable electricity to electric vehicles and better building design.

Using these at scale is politically tough and financially demanding, but the physics is simple: the less carbon dioxide that enters the air, the less we have to worry about later.

Finding balance with ocean carbon

Global climate plans often mention a target of “net zero” emissions by 2050. Net zero means that any greenhouse gases still emitted are balanced by taking the same amount back out of the atmosphere.

In reality, some sectors – such as long-distance aviation, shipping, and heavy industry – are difficult to fully clean up. Even with strong action, they are likely to keep emitting some carbon.

“We must have a net removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to get to 1.5°C and that means that you will likely have some residual emissions from some sectors, such as shipping and aviation, and some industries,” said Muri.

“And then you will have relatively large-scale removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as well, so that the net is at about between 5 to 10 gigatons of CO2 removed per year towards the end of the century, according to scenarios by the IPCC.”

In 2024, total global carbon dioxide emissions were about 42.4 gigatons, so the suggested removal would be a sizable chunk of today’s output.

Ocean tests for carbon removal

On land, some removal methods are already moving ahead. Afforestation, which means planting new forests or restoring damaged ones, is the most familiar.

There are also industrial projects, such as the Climeworks direct air capture plants in Iceland. Big fans move air across filters that trap carbon dioxide, which is then mixed with water and pumped into volcanic rock where it slowly mineralizes into a solid form.

At sea, several ideas are still at the testing stage. Some approaches protect and restore coastal ecosystems such as mangrove forests, salt marshes, and seagrass beds.

Other strategies are more intrusive, including adding iron or other nutrients to parts of the ocean to spur huge plankton blooms that soak up carbon dioxide before sinking and carrying that carbon into deeper water.

Ocean monitoring challenge

The big question for all these ocean projects is simple to ask and hard to answer: how do we know how much extra carbon they remove and for how long?

Muri explained that one needs to monitor the background level of carbon (in the ocean) and then implement one’s project, making sure to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Monitoring should then take place to determine how much carbon has been removed, and how long it stays out of the atmosphere.

A written report stating the results of the research could then be verified by an independent party. But, tracking carbon in the ocean is messy. Currents move water across long distances, mixing layers and stirring up sediments.

“If you’re storing it in the ocean, in some form or another, not in a geological reservoir, it’s a lot harder to govern it and also monitor it. The ocean doesn’t stay put,” noted Muri.

Risks of marine carbon removal

As these technologies develop, some businesses and governments are looking at them as a way to claim carbon credits. In some cases, companies already say they have started to remove carbon dioxide using marine methods.

However, Muri is cautious about this. “None of these methods are mature to use if you cannot verify impacts or where the carbon goes, or how long it stays away from the atmosphere.”

She added that if we wish to use marine carbon dioxide removal to make meaningful contributions, we need serious monitoring, reporting and verification mechanisms.

“The credit part of it also has to work right. You have to have reliable and transparent and scientifically defensible crediting systems,” said Muri.

Any reporting system also has to cover side effects on marine ecosystems. Nutrient additions can change food webs.

Large-scale seaweed farms can alter habitats and local chemistry. Changes in alkalinity from chemical methods can shift the balance for species that build shells.

No miracle fix for carbon

Despite these uncertainties, future scenarios show that we will need carbon dioxide removal in order to reach our most ambitious temperature goals that the IPCC set, which includes the 2018 special report on 1.5 °C.

“We don’t know all the threats of these immature methods yet, but it’s a bit hard to just take them off the table because they’re uncomfortable to think about,” stated Muri.

She also warned against over-selling marine carbon dioxide removal as a simple solution. “Some people are really hoping to find an answer in the ocean, but in our opinion, we’re not there yet.”

Lessons from ocean carbon removal

For now, the question is not whether oceans can remove carbon dioxide in theory. It is whether societies can control and track ocean-based projects well enough to trust them as part of climate policy.

“And there’s a question of whether it can be a scientifically governed climate solution, and we don’t have the answer to that yet. But if we want to go in that direction, then we need to clear up all of these standards and establish these properly before we can scale things up,” Muri said.

That leaves a clear message. The ocean may help with the climate fight in the future, but it cannot carry the weight of today’s choices. Cutting emissions sharply, right now, stays at the center of the story.

The full study was published in the journal Zenodo.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–