Scientists issue warning after finding nanoplastics in farm animals

From packaging to production, plastic has reshaped global food systems. It kept our food fresh, protected goods, and made life easier.

But now, plastic is creeping into the natural world in ways no one imagined. It breaks apart into invisible fragments called nanoplastics that end up in soil, water, and feed.

These tiny particles move through the food chain, passing from the environment into farm animals and finally onto our plates.

Scientists now warn that the same plastic designed to protect our food might be silently entering our bodies through the animals we depend on for meat, milk, and eggs.

Understanding nanoplastics – the basics

Nanoplastics are tiny fragments of plastic that are smaller than one micrometer – that’s less than one-thousandth the width of a grain of sand.

They form when larger plastic items, like bottles or bags, break down over time due to sunlight, waves, or friction. Because they’re so small, nanoplastics can move easily through air, water, and soil.

What makes them tricky is that they’re invisible to the naked eye, yet they can carry harmful chemicals and attract pollutants, making them potentially dangerous to living organisms.

When animals or humans come into contact with nanoplastics, these particles can enter the body through the air we breathe, the food we eat, or even through the skin.

Nanoplastics invade animal cells

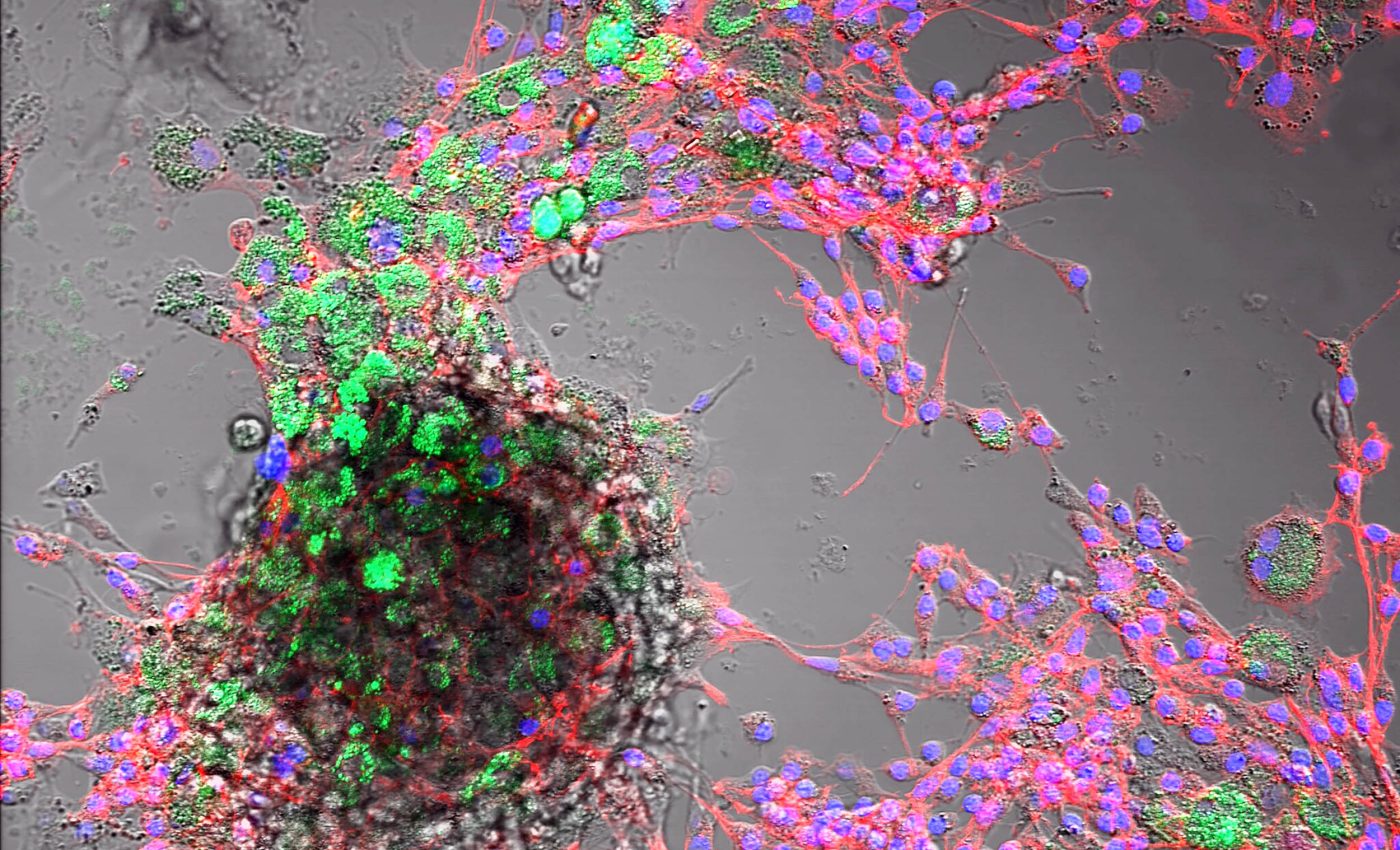

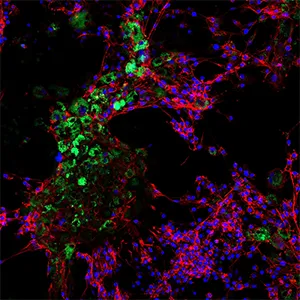

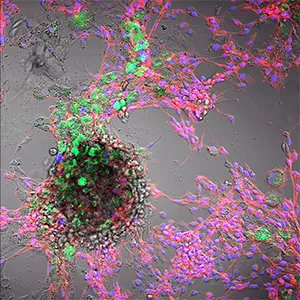

Researchers from the Research Institute for Farm Animal Biology (FBN) in Dummerstorf and the University of Udine have shown that nanoplastics don’t just stay outside animal tissues. They move in.

The team exposed cell cultures from cattle and pigs to polystyrene particles smaller than a thousandth of a millimeter. The result was clear – the particles slipped into the cells and stayed there.

“Since we still know far too little about nanoplastics and detection is difficult, our results are particularly important for better assessing the risks,” said Dr. Anja Baufeld from FBN.

“When we saw that nanoplastics were entering the cells, we knew that this could have far-reaching consequences.”

The researchers watched how the particles interacted with two types of cells – those tied to reproduction in cows and those that help form muscle in pigs.

In both systems, the plastic accumulated inside, hinting that exposure might not be harmless.

Plastic exposure weakens animal cells

The cow ovarian cells showed lower survival rates, though hormone levels stayed normal.

The scientists think the particles disrupted how the cells group together, weakening them. This interference could affect egg development and reduce fertility over time.

In the pig cells, things looked slightly different. The plastic didn’t kill the cells but slowed their ability to spread and connect.

The highest plastic concentration even reduced cell coverage, suggesting a possible delay in muscle fiber formation.

That might sound small, but in a living animal, slower muscle growth could influence both health and meat quality.

The bigger plastic problem

The study didn’t show immediate cell death or major inflammation. That doesn’t mean there’s no danger.

The plastic particles used in the lab were smooth and spherical, far milder than the rough, chemically treated fragments that exist in the real world. Those sharper particles could irritate tissues, trigger stress responses, or alter immune behavior.

Another problem is measurement. No reliable method yet exists to detect nanoplastics inside body tissues.

Scientists don’t know how much of this material actually reaches the organs of livestock. Without better tools, it’s impossible to know how serious the problem is.

How pollution enters our diets

Farm animals act as a bridge between contaminated soil and human diets. Feed can already contain plastic from mulch films, silage wrap, and fertilizers.

Once ingested, those particles may travel from the gut into muscles, milk, or eggs.

Microplastics have already been found in cow and sheep meat. Nanoplastics are even smaller and could hide deeper within tissues that humans consume daily.

“Our research shows that nanoplastics are not only an environmental problem, but could also have direct consequences for the health of farm animals,” said Baufeld.

“These initial findings highlight the importance of conducting more intensive research into plastic pollution in order to assess the potential risks to both animals and humans at an early stage.”

Growing nanoplastics risk for animals

The research, published in Science of The Total Environment, is one of the first to trace nanoplastics inside farm animal cells. It marks a shift in how plastic pollution is understood. This isn’t just an environmental crisis – it’s biological.

The FBN team now plans to explore how long these particles stay inside tissues and whether they move from mothers to offspring.

The researchers also want to learn if the contamination builds up over time. That knowledge could reshape how livestock are raised and how food safety is monitored.

Plastic pollution no longer ends at the landfill or ocean surface. It now lives inside the cells of the animals that feed us. The discovery exposes a quiet but growing threat – one that starts in the environment and ends on our plates.

Scientists believe this hidden contamination could affect animal health, food quality, and even human well-being over time. Each fragment tells a story of how plastic waste travels full circle, returning to the very systems that created it.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–