Scientists learn exactly why Shackleton's Endurance ship sank in Antarctic seas

For more than a century, people have said Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ship, Endurance, was the toughest wooden vessel of its age. A fresh look at the evidence says otherwise, and the engineering story is far more sobering.

A peer reviewed study reported that Endurance was not built for pack ice, the drifting fields of sea ice that close in and squeeze ships, and that the loss of the rudder, the plate that steers a ship, was not the single cause of the sinking.

The paper explains that repeated compressive ice loading, when moving floes press and crush, overwhelmed a hull already weakened by choices made at the drawing board.

Why the Endurance ship sank

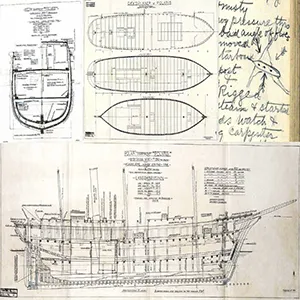

The work was led by Jukka Tuhkuri, a professor of solid mechanics at Aalto University. He examined shipyard drawings, diaries, and letters, then ran a structural comparison against other polar ships of the era.

The ship measured about 144 feet long and 25 feet across, carried a 350 horsepower steam engine, and had a very large engine room.

That layout removed supports where the hull needed them most and left fewer paths for the forces to travel safely.

The analysis found thinner deck beams and frames than seen in several peer ships. It also found no diagonal bracing that would have helped the hull stay stiff when the ice pushed unevenly.

Hull was built for the wrong ice

Endurance was designed for ice at the edges of the Arctic, where ships mostly bounce off floes. That is a very different job from being pinned inside the Weddell Sea, where the ice can trap a vessel and apply sustained side pressure.

In simple terms, strong deck beams hold the sides apart and keep the shape of the hull while vertical posts called stanchions share the load.

Endurance had fewer, longer spans, and a long open engine space that acted like a hinge running through the middle.

“Endurance sank because the vessel was simply crushed in compression by ice,” stated Jukka Tuhkuri. The conclusion matches how the ship behaved in the last weeks before it went under.

1915 journals recorded details

Crew diaries describe shuddering vibrations, buckling beams, and planks springing as pressure ridges formed and the hull bent.

Those notes point to a ship fighting the ice along its sides and bottom, not just at the stern.

The expedition’s own records describe the surrounding ice destroying the ship piece by piece as the final crush intensified, an observation that aligns with the engineering evidence of a hull collapsing under compression.

The records also describe the keel damaged and sections forced upward as ice piled under the port side.

The keel, the spine running along the bottom, helps tie the structure into one piece, so damage there makes everything else worse.

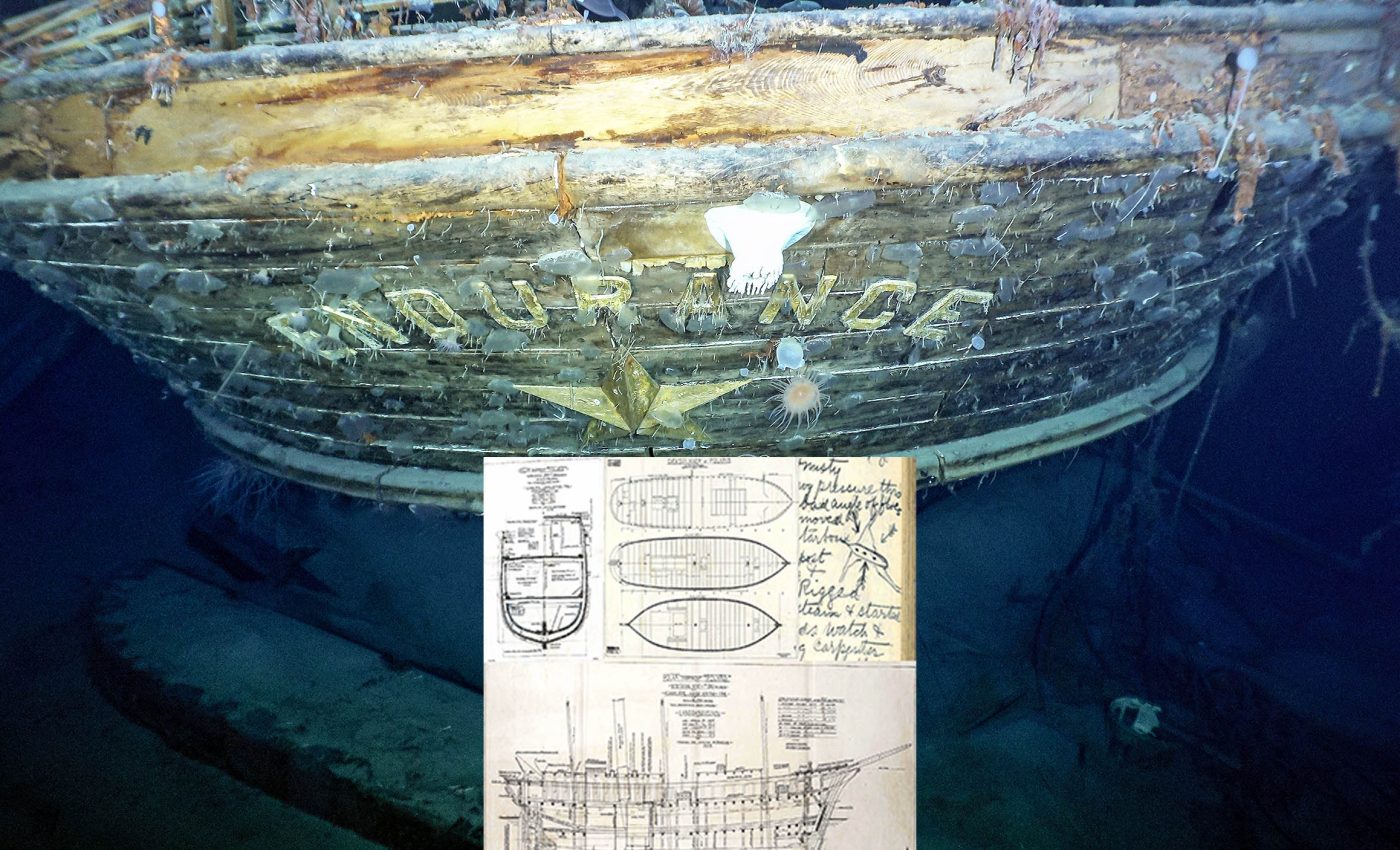

Endurance ship on the seafloor

In 2022, the Endurance22 team located the wreck at about 9,869 feet in the Weddell Sea and confirmed the site with high-resolution images.

The visibility was striking, and the stern area, including the missing rudder, was documented.

The wreck imagery supports the idea that the hull failed under pressure and not from a single snapped part. The findings pushed researchers to revisit the old legend with better data.

Design lessons in plain sight

Ships that survived serious compression were built differently. Fram, for example, used a squat shape that tended to ride up when the ice squeezed, and it carried liftable steering gear that could be raised clear of crushing blocks.

Those ships also used diagonal braces that tie the sides and decks into a stronger box. Without those braces, an off-center push can tilt a wooden hull and make it distort, which raises the risk of buckling.

Endurance lacked those features and had a deeper projecting keel than some polar designs. That made it harder for the hull to slide free when floes shoved underneath.

What Shackleton knew

The paper shows Shackleton understood Endurance’s weaknesses before departure and had even suggested diagonal supports to strengthen another expedition ship years earlier.

He judged the risks and sailed anyway, a decision shaped by time, budget, and optimism that never fully reconciled with the engineering trade-offs.

That choice does not erase the leadership he showed after the loss of the ship. It does mean the outcome was not only a story about the fury of nature but also about design limits that were knowable at the time.

Rethinking Endurance ship mythos

For decades, the public story said Endurance was the strongest of its kind and fell victim to a torn rudder.

The new evidence says the hull collapsed under compression and the rudder failure was only part of a larger structural failure.

This change does not shrink the courage of the crew. It sharpens our understanding of why the ship did not survive and how a different set of design choices could have improved the odds.

Modern polar operations still wrestle with ice physics. Knowing how deck beams, stanchions, braces, and machinery spaces share loads helps engineers design safer ships for harsh places.

The lesson is simple. Heroic narratives travel far, but the numbers inside the wood decide what happens when the ice closes in.

The study is published in Polar Record.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–